Deep in the heart of Los Angeles’s Koreatown, just a few doors down from H Mart and a K-pop music superstore, an American flag hangs over the entrance of a saloon called Eastwood.

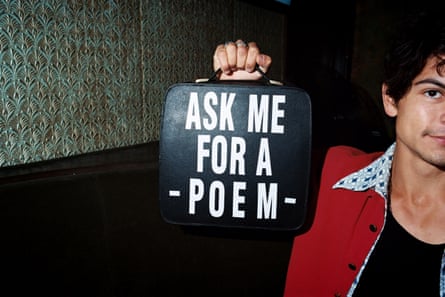

The western-themed bar would normally be cranking Luke Bryan while customers play skee-ball, line dance and get bucked off their mechanical bull named Gucci. But tonight, the music is low and the loudest sounds come from the clacking of vintage mechanical typewriters. About 30 people in the bar are drafting poems about horses, sunsets and Stetson hats – which are plentiful atop the heads in the crowd.

They’re here to take part in Cowboy Poetry Los Angeles, a collective dedicated to preserving the history of the American west through authentic storytelling. For city slickers unfamiliar with cowboy poetry, it’s a folk art that emerged from oral traditions. Around the 1870s, during long cattle drives west from Texas, men would trade stories and sing songs about their adventures on the frontier.

There’s a misconception that cowboy poetry is a dying art form, but some 150 years later, the movement is experiencing a revival. The Eastwood workshops are just one example of new poetry gatherings sprouting across the nation. In 2021, Dakota Holdaway established the Juab Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Nephi, Utah. That same year, Leslie Miller launched the Rodear in Bridgeport, California, an arts and culture festival that highlights talent from young women across the west.

While many of the US’s leading cowboy poets skew older, events like these are fast becoming a creative outlet for a younger, more diverse crowd. Cowboy Poetry Los Angeles stands out because it is one of the few scenes emerging in a major city.

Kristin Windbigler, the chief executive officer of the Western Folklife Center, which organizes the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada, is thrilled to see the group thriving in Los Angeles. “It allows cowboy poetry to reach an audience that it might not necessarily reach,” she said.

On this warm August night at Eastwood, Cowboy Poetry LA’s co-founder Amir Beardsley, 31, takes the stage. Though he’s often backed by music, today he’s performing solo to give a crisp demonstration of the art form, and chooses to recite his poem Black Friday, about the bull that nearly ended his pro rodeo career.

Heck, they thought they killed me back in 15

flew me out in a chopper, covered me with a sheet.

A big bad bull whipped me down

and sent me whirling, whirling all around.

He holds the microphone confidently as he paces on the stage, reciting the poem in a calm, rhythmic cadence. His free hand rests on his hip, drawing attention to an ornate belt buckle he won during a junior riding championship. The audience, some seated at typewriters, others in front of blank white pieces of paper waiting for inspiration to hit, listen in rapt attention and occasionally take notes when a piece of imagery feels particularly western, like when Beardsley compares rodeo tales to war stories.

When Beardsley performs, the words flow gleefully, like he’s been telling these stories his entire life. As a teen visiting Elko’s poetry gathering, he once complimented an older poet’s reading, and the cowboy offered a bit of wisdom that would shape Beardsley’s style.

“He said: ‘Young man, I recited that poem. I did not read it,” Bearsdley said. To be a cowboy poet, one has to memorize their poems.

A living history

By the time east-coaster-turned-trail-hand Jack Thorp had published the first recorded book of cowboy poems, Songs of the Cowboys, in 1908, cattle drives were on the decline. Yet the book helped spark a larger interest in the art of cowboy poetry, and people with connections to the west, whether it be through their upbringing, ranching or rodeo, began holding informal open mics where they could share their stories. In 1985, a rancher and renowned cowboy poet named Waddie Mitchell launched the first organized cowboy poetry celebration in Elko, Nevada, and today, the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering remains the largest cowboy poetry event in the nation.

Beardsley, who grew up among cowboys in rural Red Bluff, California, started writing and attending the gatherings in high school. It was there that he learned some of the signature characteristics of a cowboy poem: vividly descriptive landscapes, honoring one’s relationships with animals and an exploration of isolation or solitude.

Beyond that, a cowboy poem can take whatever form the author wants. It can be flowery or direct, it can rhyme or clash, and it can focus on the present instead of the past.

“For me, it’s about the storytelling,” Beardsley said. “A lot of my poems I started out writing were telling stories about the life I lived being a young bull-rider.”

When Beardsley moved to Los Angeles three years ago, he linked up with his cousin, Zane York, 33, a consultant at a skateboarding non-profit. Whereas Beardsley is often described as “the real deal” because he grew up in rural America, York, who functions as the Cowboy Poetry LA hype man, says he’s “a real California kid”. He grew up in suburban Claremont, where he skated in strip mall parking lots and developed his sensibilities from hippies and musicians. He’s the son of John York, a bassist for the band the Byrds, and inherited his father’s passion and aptitude for music, which blended perfectly with cowboy poems.

“I don’t claim to be a cowboy,” York admits, “but I’m still a man of the west.”

In April 2024, an acquaintance learned about Beardsley’s poems and invited the cousins to perform at a basement concert in the Venice neighborhood. Beardsley read his poems while York strummed a backing tune on his guitar. That was the beginning of Cowboy Poetry LA. Within two years, they’d participated in more than 30 events, and have played at art openings, the western-themed wellness retreat Ranch Reset and the Autry Museum of the American West, a prominent museum in Los Angeles.

The cousins had both performed at the open mic at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering and wanted to share their love for the art form with their generation. As millennials, Beardsley and York are younger than the typical cowboy poet. Most of the famous wordsmiths, like Mitchell and Red Steagall, are well into their 70s and 80s; in Elko, there are even discounted tickets for attendees under the age of 35.

Beardsley and York wanted to jump right into a Los Angeles gathering, but they couldn’t find many local poets. They realized they’d have to teach the craft to their peers, and that they could take advantage of the current trend of cowboy-core to build intrigue. Between the Yellowstone series setting streaming records and Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter tour raking in millions, western culture is more popular than ever, and the cousins attract newcomers to their workshops by advertising live country music, which takes place after the workshop, and a prize for the best western wear. It’s just a bonus that guests will also learn about the art, write a poem on a vintage typewriter, read it on stage – and maybe get hooked

Despite leaning into the current western fads, Beardsley and York don’t want writers to slip into a caricature, as they consider it a reductive portrait of the cowboy. Rather, they want to help people embrace that authenticity actually means recognizing that the west has always been a diverse place.

York points out that “Gene Autry was the first movie star in the USA, and he was a white cowboy who had a rifle and fought Indians”. Unlike these Hollywood stereotypes that embody colonial ideas like manifest destiny, machismo and hyper-masculinity, the cowboy evolved from vaqueros, or Mexican cattle ranchers, and historians estimate that one in four cowboys were Black.

This issue is deeply personal to the cousins, who identify as Arab Americans of Jordanian descent. Beardsley said that he never met another Middle Eastern competitor while on the pro rodeo circuit, and thinks he may have been the first. Other riders would razz him for his heritage, but it only made Beardsley bolder, and he commissioned a pair of chaps with the colors of the flag of Jordan to wear during competition.

“I say I’m half Jordanian, half cowboy,” Beardsley says.

Windbigler has worked hard to bring more poets under the age of 40 to the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, and at the next event, they’ll represent at least one-third of the lineup. Windbigler is especially thrilled to welcome Los Angeles Cowboy Poetry as special guests for the upcoming gathering in January, where they’ll be bringing their typewriters and facilitating a workshop similar to the one they host at Eastwood.

She also pushes back against the idea that cowboy poetry is a dying art, noting that the gathering’s ticket sales have grown 53% in the past decade. In 2025, roughly 8,000 people came to Elko, surpassing the peak attendance the gathering attracted in its early heyday.

As cowboy poetry gains renewed popularity with young folks, it also sparks dialogues between generations. Elders pass on their lyricism, knowledge and stories, helping the younger poets become stronger writers. In return, the younger generation preserves their mentors’ legacies by learning their poems and reciting them at their events, helping the tradition stay alive.

“Our whole deal is passing on these creative traditions to the next generation,” Windbigler said. “You can’t do that if the older generation isn’t there or the younger generation isn’t there.”

Back at Eastwood, Beardsley gently checks in on the burgeoning poets. He weaves through the crowd with a black cowboy hat filled with poetry prompts for struggling authors. They include wistful images, like “write from the perspective of someone watching a cowboy ride away”, and reflective challenges, including “a moment when the rope missed – or landed – at exactly the right time”.

The bar hosted events throughout the autumn, including one in November attended by Charles McGarrigle, 30, a story producer in the entertainment industry. At that event, he wrote a poem about his partner, Lauren Hofschneider, 31, a psychology professor, who was born on the island of Saipan and moved to California after she turned 18. Despite the apparent cultural differences between islanders and people from the west, Hofschnieder’s journey of migration and isolation, of moving alone from a small, remote town to a hustling city, felt in line with the cowboy experience.

“I don’t see myself as a cowgirl, obviously, but him phrasing it that way made me realize there have been many moments in my life where I was wandering alone,” Hofschneider said.

This was McGarrigle’s second workshop, but his first time reading a poem. “I didn’t perform because I was almost intimidated by so many cowboy hats and thinking that I didn’t belong, and I’m a poser,” he explained. “But Amir and Zane do such a good job of reassuring the crowd by saying, even though the theme is cowboy poetry, it’s just about getting up on stage.”

Katie Meza, who attended her first workshop in August, also felt that Beardsley and York quickly embraced her.

“I’ve never touched a horse in my life, but we all get to appreciate the culture equally,” Meza said.

She came to the August event with her ex-boyfriend, Michael Salonius, 51, an elk rancher from Crescent City, Oregon. The 13th-generation mountaineer grew up hearing cowboy poetry in his hometown bar, and was excited when he discovered the event through Instagram. He was bracing for a dingy room with just a handful of old men, and was shocked by the young, energetic crowd.

“It exceeded my expectations,” Salonius said. “To see this many young people doing it, taking it seriously, and the diversity of poems … ” He trailed off, then cracked a wide smile. “It’s fucking rad,” he said.

Towards the end of that night, Jarod Ramirez, 25, took the stage. He grew up in Hesperia, a town surrounded by the Mojave desert, and said the workshop was helping him reconnect to his roots. His grandfather was born in New Mexico, and Ramirez remembered him as the embodiment of a western lifestyle. He sported his grandfather’s old silver bolo tie, which was in the shape of a bean and embedded with red and blue turquoise stones.

“This is my first time doing cowboy poetry, so we’ll see if it’s good or not,” Ramirez said, then launched into An Ode to the Hatch Chili:

Green or red

the favorite color can end in a brawl.

But you’re more subtle than that.

If asked, I’d say green,

if one appreciates the color of cacti and spikes of Joshua trees,

red if you’re hot-blooded and savor the sunset.

But what is it that makes you so special?

Being of Old Mexico. I’ve had my fair share of spices

but my New Mexican family

had some kind of magic.

They capture the taste of a wild desert, fire,

and put it on the top of my tongue.

The audience loudly clapped and cheered. With that, Ramirez was on his way to becoming a cowboy poet; all he needs to do is write, be kind and nurture his appreciation for the west.

“I like to tell folks being a cowboy, it’s not what you do, but who you are and how you respect yourself, others and the land,” Beardsley said.

1 month ago

30

1 month ago

30