A few weeks ago, Michelle Jackson was in the Peak District, hiding beneath a camouflage net with her camera, waiting for badgers to emerge at sunset. For more than two hours she watched the skylarks and curlews, her hopes intensifying during the 45-minute window in which the light was perfect.

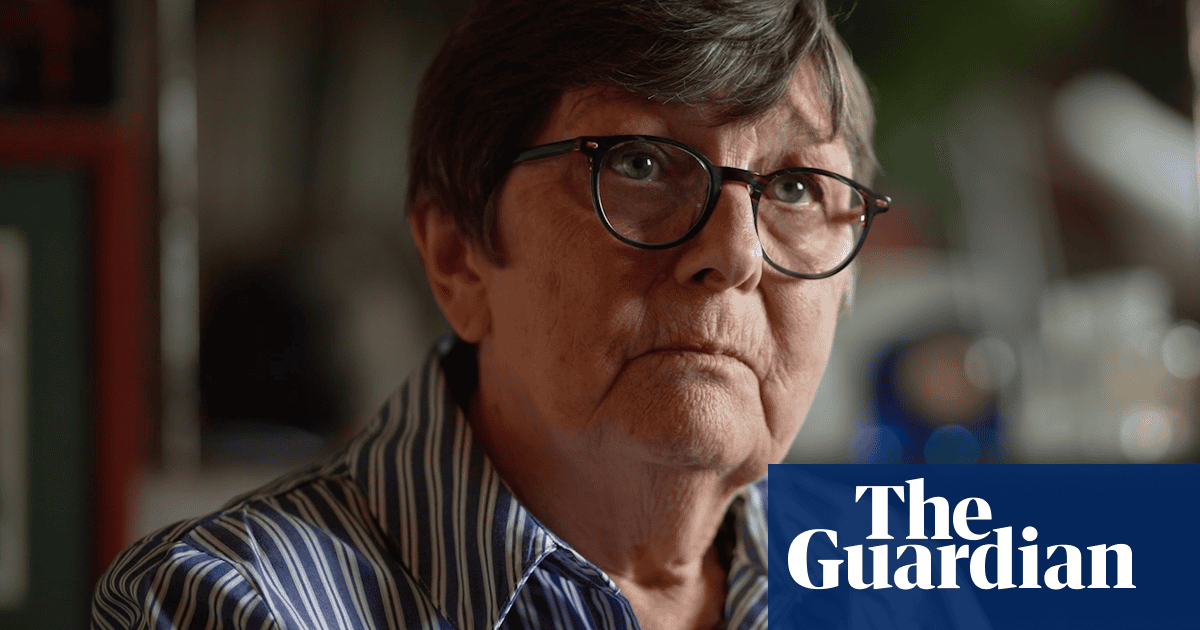

At last the heather moved. A badger’s head appeared. “Their eyesight is poor, but they can smell you,” Jackson says. At 66, she has won national and international awards as a wildlife photographer. Although the desire to get the shot “drives” her, for a while she simply watched. “You want to embrace what’s there. It’s so special to see wildlife up close.”

At least two of the shots Jackson took that evening are “competition-worthy”. Yet she didn’t pick up a camera, beyond a simple point-and-shoot, until she was 61.

Jackson, who lives in Derbyshire, England, spent most of her working life as an engineer in the rail industry. In 1978, she was one of the first two women taken on by British Rail as design engineers. She designed carriage systems for the Channel tunnel trains, and regards the British Rail Class 91 high-speed electric locomotive as “my baby”; she managed its emerging weight and balance.

In 1994, she and her husband, also an engineer, moved from the UK to Sydney, Australia. She worked, or spent time with their two daughters. “I didn’t put aside time for myself.”

Jackson retired at 56 when her hearing became impaired. “Meetings were very social. Cafe environments, hard surfaces, clitter-clatter, people talking in the background. I realised I was missing too much. I didn’t want to embarrass myself or the organisation I worked for. So I decided to give up,” she says.

She didn’t ask for adjustments to the meetings?

“I probably didn’t want people to know.”

In 2018, she and her family returned to England. “What am I going to do now?” she thought. “The emails went from 550 to 50, and 20 of them were junk. I needed something to stimulate me.”

The following year, at 61, she bought her first DSLR camera and joined a local walking and photography group; then, when Covid hit, she enrolled in an online photography and Photoshop course. A history of pneumonia meant she had to shield, so she photographed whatever she could find indoors – still life, flowers, pets. “If I’m going to do something, I’m going to do it properly.”

Jackson publishes under the name “Emmabrooke”, after years of being presumed male in engineering and mistakenly being called Michael. But she brings to her camera “an engineering brain … I do everything in manual”.

She has always loved nature. In her 20s, she hiked long distances, including the 268 miles of the Pennine Way in northern England. “Nature, seeing the big picture of landscapes, has always been there. But I didn’t use a camera,” she says. It was only after retirement that the camera became “a means to capture what I’d seen. The things you take for granted.” Even planning a boat trip to see humpback whales, “I didn’t consider buying a decent camera. I was just enthralled by seeing: the fact you could see them, rather than have a photograph to remember them by.”

Maybe there is a connection between hearing loss and wanting to “capture” the environment she witnessed? Jackson’s images are sharp and crisp, and the result of an acutely focused anticipatory vision. “I have a mind’s eye of what I’d like to get,” she says. She once waited hours for two gannets to bring their heads together in the shape of a heart.

“When you lose a sense, other senses get stronger,” she says. “I’ve got my eyesight.”

Jackson is preparing for her Master Craftsman award with the Guild of Photographers. She achieved her associate level with the Royal Photographic Society last year and is now aiming to achieve fellowship. She spends at least 20 hours a week in the field. “I’m besotted with British wildlife. I get excited each time,” she says. Whether she is photographing badgers, ospreys, kingfishers or a golden eagle in the snow, she says: “It’s the thrill of them turning up. If you really want to seek them out, you’ll find them.”

You can see Michelle Jackson’s work on her website, on Instagram and on BlueSky

3 months ago

49

3 months ago

49