On a recent afternoon in Santiago, several thousand people gathered to mark the fifth anniversary of the vast protest movement which rocked Chile in 2019.

That same day last month, Sebastián Méndez, 38, who was blinded in his right eye by a projectile fired by a police officer at a demonstration that year, took his own life.

According to organisations working with the victims of eye injuries, Méndez is the fifth to have taken their life as desperation mounts and state support remains insufficient.

According to official statistics, 34 people were killed and as many as 460 suffered eye injuries as the Carabineros police force fought to repress the protests across months of unrest.

Among the shootings and beatings which made up the majority of cases, torture, rape and instances of detainees being stripped naked were also documented.

But momentum in the push for justice has dissipated almost entirely. Five years on, thousands of victims are trapped between hopelessness and impunity.

Many Chileans are still picking up the pieces.

Among them is Susana Alarcón, a 57-year-old daycare assistant from Maipú, a sprawling southern suburb of the capital.

Her son, Jorge Salvo, was blinded in one eye by a teargas canister fired from close range by a police officer in January 2020.

Three years later on 18 July 2023, he left a farewell message on his mother’s voicemail, explaining that he could no longer cope.

Salvo took his own life that evening.

“Jorge was very sensitive, emotional and caring,” remembers Alarcón as she sits beside a small shrine in her living room.

A candle is lit next to two photos of her son, and a black rose pokes up from a vase of white plastic tulips.

In a box of his possessions is his prosthetic eye – a white-iris sphere emblazoned with an anarchist “A” – as well as the chipped gas mask he would wear to protests and several pictures of a one-eyed man in a superhero’s cape drawn by his five-year-old daughter.

“The day the protests started, he came home and said to me ‘mum, I have to be there, there’s too much injustice.’ There was no way back for Jorge once the protests began.”

Millions of Chileans shared his concern.

On 25 October 2019, as many as 3 million people marched in the largest protests the country had ever seen.

Bewildered, the leaders of most of Chile’s main political parties signed a “peace accord”, which paved the way for the replacement of its 1980 constitution, which dates back to Gen Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

That process eventually failed, and a second constitutional proposal was rejected last year.

Doctors could do nothing to save Salvo’s left eye, and during a long and painful recovery, Alarcón took down all of the mirrors in the house as her son could not bear to see his reflection.

He lost his occasional construction work and was left without employment or consistent support, despite a psychological and medical programme put in place in 2020 under former President Sebastián Piñera that had initially proved successful.

However, the pandemic saw the support on offer slow to a trickle.

President Gabriel Boric announced a new programme under the management of Chile’s health ministry after taking office in 2022. The ministry declined a request for comment.

It was not until just before Salvo’s death, more than three years after his injury, that he began to receive a small compensatory pension.

“The approach has been piecemeal and disjointed,” says Marcela Zúñiga, a researcher at the human rights centre of Diego Portales University’s law faculty.

“At every turn, efforts have been made with whatever resources they had available at the time. This needs to be far more comprehensive than a symbolic monthly payment.”

Chile’s public prosecutor says that 84% of the 10,142 cases brought in relation to the repression of the protests have already closed without conviction.

Just 43 sentences have been passed. And as time slips by, hopes of further prosecutions have faded almost entirely.

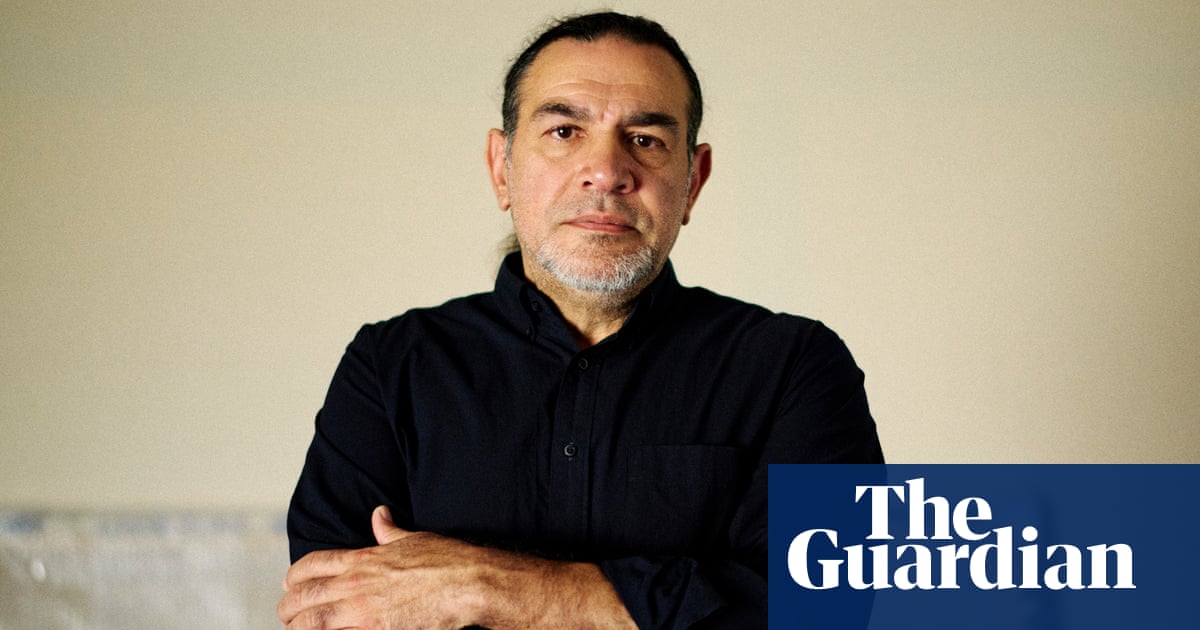

“What motivates me is to fight against Chile’s huge inequalities,” says Gustavo Gatica, who lost his sight entirely when he was shot by a police officer.

In darkness, Gatica managed to finish his studies and graduate with a psychology degree. He now tends to patients largely via online consultation.

“People were killed, blinded or confined to wheelchairs, so we cannot forget what the state did to those who asked for dignity,” he said.

“Clearly, there is responsibility on the part of the Chilean state for the massive and systematic human rights abuses during the protests.”

On 4 November, the officer who shot Gatica was put on trial with the prosecution seeking a 12-year jail term.

Meanwhile, the victims have become a community, despite divisions emerging between different groups. Gatica says he is planning on launching a suicide prevention programme.

But the legacy of the protests is uncertain.

According to one recent poll, half of Chileans believe that the movement was bad for the country, compared to just 17% who think it was good.

Sectors of the Chilean right have done their best to paint the protests as a minor criminal uprising.

“This story is written in blood, and some of that blood is Jorge’s,” says Alarcón bitterly. “It doesn’t matter how many walls you wash down or how much graffiti you paint over.”

She says that she is forced to relive her trauma every day when she passes police controls.

“The day the Chilean state mutilated Jorge, they mutilated a whole family,” she says, tears welling in her eyes.

“They left me without a son, a girl without a father; and Chile without justice.”

3 months ago

50

3 months ago

50