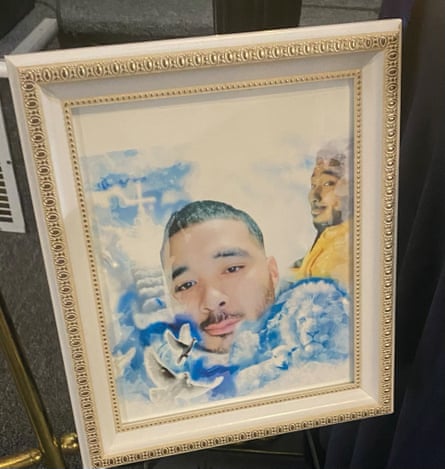

Two days before he died, a 33-year-old father and US army veteran named Glenn Smallwood Jr was talking about building a house. His younger brother, John, was remodeling a home in Lufkin, Texas, where both brothers lived, and Glenn asked whether he could help.

“He was so happy about the idea of working with me and turning his life around,” John said. “He was thinking positively about his future. I think about this memory often.”

Roughly 48 hours later, on 16 June 2023, Glenn Smallwood was arrested for public intoxication. The body-cam footage would show he was clearly in the middle of a mental health crisis as, for most of his adult life, Smallwood had had schizoaffective disorder, a condition that can cause depressive thoughts, paranoia and hallucinations.

Nevertheless, after he arrived in Angelina county jail, a team of officers strapped Smallwood to a chair, later telling his brother this was standard practice for people who are intoxicated. That’s when Smallwood started retching and fading in and out of consciousness. Several of the guards laughed, then placed him in the holding cell where he would later die. (The coroner ruled it an accidental death from the effect of methamphetamines.)

His death, and his shocking mistreatment at the hands of law enforcement, underscore how people with mental illness are at risk when they encounter the police in the US. The Washington Post’s Fatal Force database shows that one in five people killed by police may have been experiencing a mental health crisis when their lives were taken, while another study shows people with mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter.

Other data indicates this problem is particularly acute in Texas. In Dallas-Fort Worth, for instance, a 2021 investigation by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram revealed that one in three people killed by police from 2014 to 2021 were experiencing a mental health crisis when they were killed. In 2019, the University of Texas at Austin revealed that the police department in the state’s capita had one of the highest rates of police shootings of people suffering from mental illness, while also pointing out that Texas has one of the worst records in the nation for providing comprehensive mental health services.

In other words, Texas is where a troubling history of police brutality collides with poor mental health funding. Despite having the second-largest economy in the country, the state consistently ranks near the bottom of all 50 states in mental health services spending per capita.

Greg Hansch, executive director for the Texas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said that Texas simply doesn’t have enough mental health infrastructure.

“We don’t have enough beds, but it’s also more than just beds,” Hansch said. “You need a full continuum of care. And a lot of people who would be involuntarily hospitalized would actually do better in a 48- to 72-hour stay in a crisis facility.”

He added: “Other states are doing a better job with building out the services that need to be in place to keep people out of jail. If you don’t have this continuum, then police really are limited in their options in terms of a place to bring a person to. They will look for a reason to arrest the person, because they know if they don’t arrest the person, there’s not another place for them to go.”

For Hansch, Smallwood’s plight calls to mind Sandra Bland, a woman who was found hanged in her cell in Waller county, Texas, in 2015. The outcry and advocacy that followed her death led to a new law named for Bland, but before it was passed, key provisions were stripped from the bill.

One such provision would have limited arrests for class C misdemeanors like public intoxication, the charge for which Smallwood was booked.

That night in June 2023 wasn’t the first time Smallwood was arrested, but John wants the world to know that his brother had “a big heart”. He never wanted to hurt anyone. Indeed, he enlisted in the US army to help other people. His compassionate streak continued after he returned from military service. At one point, he literally saved a cat from a tree.

“Nobody wanted to get the cat because of how high up it was,” John recalled. “Without hesitating, Glenn began to climb the tree to rescue the cat.”

As Smallwood climbed higher, so did the cat. He finally caught and returned the animal to safety, then hugged its owner as she cried with relief.

“I was so proud of him,” John said. “I thought it was the coolest thing ever.”

Another time, when the Smallwood boys were growing up, John was frustrated that he had to share a bike with his sister. When Glenn caught wind that a neighbor was about to throw out an old, broken-down bicycle, he asked if they’d give it to him instead. He then fixed it up so his brother could have it.

“We didn’t have much,” John said, “so he would always make up games for us to play or find things to entertain us, while my mom worked two jobs.”

Later, John added, “I would like everyone to know that Glenn was more than his mistakes. He was a good person.”

Jail records detail what happened to Smallwood once he was inside that holding cell. The treatment he endured is at the center of a lawsuit filed by his brother. Smallwood remained confined to the restraint chair – a practice long decried by the United Nations – and, when a nurse found him unconscious, she forwent any calls to a hospital or a physician, instead relying on smelling salts to keep him awake. Less than two hours later, after the nurse had left, officers noticed Smallwood had stopped breathing. An ambulance was called to take him to the hospital, where he died shortly after.

The choice to keep him in the chair for hours at a time, even as he retched, vomited and drifted in and out of consciousness, is a key point in John’s lawsuit, through which he’s suing the county, one of the Lufkin police officers, the nurse and the for-profit healthcare entity that employs the nurse.

Why, John wonders, did none of these people call for help sooner?

“Restraint chairs are designed to secure violent, aggressive or uncontrollable people,” said one of John’s lawyers, Erik Heipt. “Yet, the Angelina county jail routinely uses them on people like Mr Smallwood who pose no safety threat. This practice is unconstitutional.”

Worse yet, the morning he was arrested, Smallwood walked into a health facility seeking medication. Facility staff put in motion a transfer to a hospital where he could receive longer-term care, but he left before the transfer could be made.

Through a judge, the facility then issued a mental health warrant, also known as an “emergency detention”. This gave police the authority to take Smallwood to a mental health facility, though that of course didn’t happen – even though police encountered him that same day.

According to Krish Gundu, co-founder and executive director of Texas Jail Project, law enforcement officers often don’t have access to people’s full histories, including warrants like these.

“We’ve been saying that a very key piece of data that’s missing is emergency detentions,” she said. “Because how many times do we hear about people going through emergency detention over and over again, and the officers not knowing that there was this history, and they end up in jail, or they end up being murdered by the officers or use of force, because law enforcement and jails do not have access to that essential history of multiple emergency detentions.”

That said, in the body-cam footage of Smallwood’s arrest, one of the arresting officers can be heard talking to a dispatcher who shares how Smallwood ran away from a treatment center that same day.

“They were looking for him,” the dispatcher tells the officer, who moments later places Smallwood in a car en route to the jail. After shutting the door on their detainee, the two arresting officers agree the arrest “went better” than they had thought it would.

Gundu said this was the first of “multiple failures”.

Even if they hadn’t known about Smallwood’s well-documented history of mental health issues, the officers could have driven back to the hospital. Or, upon the arrival of the sheriff’s office, they could have done the same thing. Instead, five officers worked together to tie Smallwood to a restraint chair, despite the footage showing that he was docile and compliant.

What’s more, according to records reviewed by the Guardian, jailers didn’t complete the required continuity-of-care query on Smallwood, which would have used an online system to review his history of mental health care. Further, according to the sheriff’s official timeline of events, at least 16 minutes passed between two of the checks jailers are required to document when someone is in restraints. The Texas Commission on Jail Standards calls for checks to be conducted “every 15 minutes, at a minimum”.

The sheriff’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

At the state capitol, there’s some legislation that could help people with mental illness, including a bill filed by the Democratic representative Donna Howard. The bill, which needs to make it out of committee before it can be voted on, would authorize paramedics to temporarily detain people they believe are experiencing a mental health crisis. The lawmaker has been talking with Republican colleagues in an effort to sell the legislation, and she says some are receptive – especially those who hear from law enforcement officers overwhelmed by mental health calls.

“This is not about saying paramedics are going to have to be police officers,” Howard said. “To approach [mental health calls] with more of a public health-centered approach than a law enforcement-centered approach is really the overarching goal here.”

Meanwhile, John Smallwood isn’t waiting for new bills to seek some kind of justice for his brother.

“Life has been a blur since my brother’s death,” he said. “I still haven’t come to terms with it, to be honest.”

He often wakes in the morning with a pain in his chest, and for that moment, he feels like Glenn’s death happened all over again. It feels like he just got the call that came almost two years ago.

“He’s my big brother,” he said. “I was born into this world knowing him. I think about him all the time. He always gave me advice and encouragement. He believed in me, and I could depend on him for support. I lost all that. It’s now gone forever.”

“When he died,” John added, “a piece of me died.”

3 months ago

70

3 months ago

70