Hamish Wilson lives a few miles away from me, in a cosy farmhouse in the damp hills of mid Wales. He makes good coffee, tells great stories and is an excellent host. Every summer, dozens of Somali guests visit Wilson’s farm as part of a wonderfully wholesome project set up to celebrate their nation’s culture, and to honour his father’s second world war service with a Somali comrade-in-arms.

Inadvertently, however, the project has revealed something else: a deep unfairness in today’s global financial system that not only threatens to ruin the Somalis’ holidays, but also excludes marginalised communities from global banking services on a huge scale.

The origins of the story lie in 1940, when the then 27-year-old Capt Eric Wilson led a doomed stand against an Italian invasion of the British colony of Somaliland. Suffering from malaria, massively outnumbered and under heavy artillery fire, Wilson and a small band of Somali comrades – like the Spartans at Thermopylae, but wearing khaki shorts rather than leather drawers – held off the Italians for an astonishing five days.

After their position was overrun, Eric won a posthumous Victoria Cross, which came as a nice surprise when he was liberated from a prisoner of war camp a few months later. It was an extraordinary honour, the highest a British soldier can receive, but he was always troubled by it. Why had he been recognised, while his sergeant – an old friend called Omar Kujoog who had died in the battle – received nothing?

Wilson, my neighbour in Wales, inherited his father’s passion for east Africa, and spends a lot of time there himself. He and his friends, who included Kujoog’s son and grandchildren, became increasingly concerned that young Somalis in the UK were losing touch with their traditions, and only learning about their homeland from the media’s negative coverage of it.

So, before Eric’s death in 2010, they sold the Victoria Cross and bought the farm to create a centre for Somalis to learn about their nation’s culture, as well as to commemorate the ties between the Wilson and Kujoog families. They called it Degmo, the Somali word for an encampment used by nomadic herders.

Every summer, groups of people come to stay here, each chipping in a bit of money to a charity established by Wilson so he can pay the bills. His Somali visitors camp in gleaming bell tents and eat in dome-shaped pavilions. Wilson arranges activities around the farm – the kids round up sheep, walk through the woods and lie under the stars looking for meteorites – while old Somali women amaze their grandchildren by being able to effortlessly milk goats or move stock, and gain a new audience for stories about what Somalia was like in their youth.

It is a lovely project, but in some ways, it is not a particularly unusual one. Farmers often earn extra income by hosting city-bred campers. What is unusual, however, are the problems that Wilson has with his bank. “They phone me up and say, ‘I need to ask you some questions about your account,’ and they go through the charity account and ask me questions about the source of every amount of money that went in or out,” Wilson told me. “Every time they ask the same questions, and I say, ‘Well, look, I told you this two or three weeks ago when you spoke to me,’ and it is always another half-hour of my time.”

The problems he has are nothing compared with those of his guests. One community leader from Birmingham – accompanied by her daughter, who helped to translate some of the more technical language – told me how hard it had been to bring a few dozen Somalis to the countryside for a weekend. It’s only a two-hour drive, so the logistics are straightforward, but the finances had been a nightmare. She had assumed that paying Wilson for the food and accommodation would be easy. Other Somalis could transfer money to her account, then she would pass it on, which would allow her to keep track of who had paid and how much.

About £4,000 had moved through her account between July and September the year before, and that’s when the problems started. Bank compliance officers summoned her to meetings and went through every transaction, demanding to know who these people were that were sending her money, how long she had known them and where the money had come from. “It almost made me feel like we were doing something wrong, almost like we were money laundering,” she said, with disbelief in her voice.

And that was just the start of it. She had planned a trip to Somalia to see relatives, and transferred money to her sister so they could buy plane tickets together, but then the bank froze the money, making it impossible to buy anything. She set up a savings club with friends, with the idea that they would each put in £200 a month, then take out £2,400 once a year; but the bank froze that account too.

The tiniest things set off the bank’s suspicions. If she writes a payment reference for an online transfer in Somali rather than in English, the transaction is blocked. If she moves more than £250 at a time, the transaction is blocked until she explains the origin of the money.

“A lot of people in our community are struggling with this but they prefer to leave it alone. The worry is that if you complain there will be even more questions,” said the Birmingham community leader. “The days when I have to go to the bank are the worst days. I never want to go to the bank.”

Just like most people who holiday in this part of Wales, the campers are British citizens; they live in the UK and they use British bank accounts. So, what is it exactly about people who come to Wilson’s farm that is different from the campers at other farms?

“It doesn’t matter that I’m a British citizen, it’s just that I’m poor – and there’s this,” said the community leader, tracing a circle around the edges of her hijab with her finger, before giving a shrug and a rueful smile.

The uncomfortable reality is that, unlike most campers in this part of the world, the community leader and her friends are Black and Muslim. And people who are Black and Muslim are some of the primary victims of a system that was set up after the attacks of 11 September 2001 to stop terrorists from moving their money around. It’s a system that has failed to achieve its primary aim – terrorists are every bit as widespread now as they were two decades ago – while making life much harder for millions of innocent people.

After 9/11, officials wanted access to every tool that might help them save lives, and they thought tracing financial movements could be one of them. Within days, the UN security council demanded that all countries establish a system for freezing terrorists’ assets. In October 2001, the US president, George W Bush, signed the USA Patriot Act, which expanded anti-money-laundering rules to cover terrorists. That same month, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an inter-governmental body established in 1989 to craft a global approach to money laundering, published recommendations for a “basic framework to detect, prevent and suppress the financing of terrorism and terrorist acts”.

The FATF had been created at the height of the “war on drugs” to stop criminals hiding their earnings. The organisation spent the 1990s persuading, bullying and cajoling every country in the world into adopting common standards on regulating the financial system. Its primary weapon was to demand that professionals report suspicious transactions to the authorities, thus allowing governments to stop dirty money at source, with large fines and criminal prosecution for non-compliance.

On one level, since the FATF was the place that knew about dodgy money, it made sense to deploy its expertise against terrorist financing too. On another level, it made no sense at all. Money launderers take large volumes of dirty money and wash it through the financial system to make it look clean; terrorists take small amounts of clean money and – by using it to fund violence – turn it dirty. Why should mechanisms designed to catch one be able to pick up on the other?

And there was another problem: terrorists’ money only becomes criminal after they’ve committed their atrocities. For banks to be able to block it preemptively, they needed to have an insight into something they couldn’t possibly know: their customers’ future plans. Without that knowledge, they’d have no idea what they were looking for. Richard Gordon, a lawyer who worked for the International Monetary Fund at the time, says he tried to warn participants that they were acting too hastily. “To say that banks have to figure out on their own what’s terrorism finance, that’s lunacy, and I said that too. Didn’t matter, I was overruled,” he told me.

So the FATF’s proposals were adopted. No banker wanted to be caught moving money for terrorists, mainly because they were appalled by what had happened on 9/11, but also because the consequences for them and their employer would be so costly if they did. In 2004, family members of the victims of a Hamas attack in Israel sued Jordan’s Arab Bank in a US court, alleging that by holding bank accounts for members of the organisation it had assisted in the murder of their loved ones. The case was settled, but the payout was vast, even though Hamas was not an illegal organisation in Jordan. Arab Bank warned that the case “exposes the banking industry to enormous liability for nothing other than the processing of routine transactions and the provision of conventional account services even if all governmental requirements are followed”.

It was a tough position to be in. Banks had no idea what terrorist fundraising looked like, and yet faced huge fines if they were complicit in it. Desperate compliance officers scoured official documents for even the tiniest suggestions of what to look for and, in guidance published by the FATF in 2002, they found a useful hint. “Often such fundraising is carried out in the name of organisations having the status of a charitable or relief organisation, and it may be targeted at a particular community.”

It is true that some charities – or non-profit organisations (NPOs) – had been used in raising funds to support terrorist groups, but so too had businesses, criminal gangs, wealthy individuals and more. But that didn’t matter; banks now had something to look out for: a “charitable or relief organisation … targeted at a particular community”. That dog whistle was loud enough for even the deafest compliance officer to hear.

In the decades since, humanitarian, charitable and cultural organisations run by Muslims, focusing on Muslim beneficiaries, or targeting their efforts at Islamic countries have been stripped of their bank accounts – “debanked” is the usual term, although “de-risked” is also used – to an astonishing degree. This has happened throughout the world, including in Muslim countries, where bankers are just as concerned about being fined as their counterparts in Europe or North America, if not more so. And it gets almost no attention.

A poll conducted in 2022 in the US showed that more than a quarter of Muslim respondents reported having problems with their bank, such as being refused an account or having one suspended, which was more than three times as high as the rate for White evangelicals. While the reasons given to other members of the general public for their banking problems tended to be related to their credit score or overdrafts, Muslims reported that they’d been cut off because of international transactions, because they’d sent or received funds from an unfamiliar person, or been flagged for “a key word”.

It is that last point that seems to explain what happened in July 2014 in the UK, when HSBC wrote to a whole group of Muslim-focused NPOs on the same day to inform them they were losing their bank accounts. The Finsbury Park mosque in London, the Cordoba Foundation thinktank, the Ummah Welfare Trust, as well as others, all received the same letter: “I am writing to inform you that HSBC Bank has recently conducted a general review of its portfolio of customers and has concluded that provision of banking services … now falls outside of our risk appetite,” the letters stated. “I am sorry we are unable to continue to provide you with banking services, but do thank you for your custom to date.” There was no possibility of appeal, no explanation and no warning, just two months to find another bank account.

And that was just one bank. In 2016, the Co-operative Bank cut off Friends of Al-Aqsa, the Palestine Solidarity Campaign and 25 other pro-Palestinian groups. Four years earlier, Islamic Relief Worldwide, Britain’s largest Muslim NPO, which operated in more than 30 countries, was blocked by UBS. Walid Safour of the Al-Amal Foundation, and formerly of Human Care Syria, lost his personal bank account (as did his spouse), as did all his fellow trustees, with no explanation given.

The same thing happens all over the world. In 2006, FBI agents raided a Muslim-run humanitarian organisation in Michigan. No charges were ever filed, but it lost its accounts. In 2019, a Canadian NPO was cut off after a manager was charged with terrorism offences in Pakistan. The manager was acquitted, but it lost its bank account anyway.

This is more than an inconvenience. Charities rely on regular donations to keep operating, but if bank accounts are closed, donors will need to set up their donations again. How many of us get around to doing that? And the stigma is contagious, so the problem persists. “Once you’re flagged, it’s very difficult to find another bank that will be willing to do business with you,” one NPO director told the authors of a US report into debanking.

The director spoke anonymously, as does almost everyone affected by this problem (you’ll notice that, in this article, I’m quoting almost no one by name). “This is fundamentally a story about shame. It is shame that has kept this story shrouded in obscurity so long,” wrote the author of a report published by the National Council of Canadian Muslims, which quoted representatives of five different NPOs. “They all asked to be anonymous for this report. That’s because the shame and social stigma of getting ‘debanked’ remains to this day.”

I am not underestimating the importance of fighting terrorism. I reported for years on atrocities committed by militants fighting for an independent Chechnya. I saw the huddled bodies of young people murdered outside a concert, the scraps of flesh in the snow after a suicide bombing, rows of dead children whose only crime was to turn up to school on the wrong day. A good friend died in a bombing, and I miss him still. Terrorism is grotesque. But you don’t fight terrorism by ostracising blameless people, or by alienating whole classes of the population.

“Can we speak of racism here?” asked Mohamed Ibrahim, director of the London Somali Youth Forum. Banks all strenuously deny that they are targeting Muslims specifically because they are Muslims, and I’m sure they’re telling the truth. So what is the mechanism by which this is happening?

It derives, I think, from compliance systems that rely on databases that gather media publications from all over the world so they can be searched for “adverse news”. If there are negative news stories about you, you might be a terrorist, and no bank wants to take the risk of being prosecuted, so you get debanked.

Muslim names are distinctive, and they are often shared by many different people. It’s not hard to imagine that searching for someone by name in a database will throw up multiple news reports. In that case, a bank would have no idea if the individual mentioned is their client or someone else, but may close the account rather than take a chance on it. One researcher told me she’d seen an organisation flagged because it was in the same office block as a mosque. They were completely unconnected and three floors apart, but they shared an address and that was enough to raise suspicions.

In 2007, the FATF sought to correct the situation by introducing what it called the “risk-based approach”, which instructed financial institutions to focus on individual account holders, rather than on whole classes of people. Banks should not, for example, debank someone just because their organisation has the word “Syria” in the title, but rather because it supports terrorist groups in Syria. Some 14 years later, the FATF chided banks for their failure to heed this clarification in a report called Unintended Consequences, which claimed that wholesale debanking is “by definition inconsistent with a proper application of the risk-based approach”.

This report may be one of the more foolish publications I have read in a career that has involved reading many foolish publications. Not only was it two decades too late, but it drew completely the wrong conclusion. If you instruct people to do something, but all of them do something else, it would surely be wise to at least ask if the fault might lie in the original instruction rather than in everyone’s interpretation of it.

The place the FATF should have started was with that word “risk”, and what it meant to different people. For the FATF, the risk in question is that of moving suspect cash, whether it belongs to criminals or terrorists. But for financial institutions, the risk is of being fined. And that makes perfect sense. They are profit-making businesses, and anything that might stop them making a profit is something they need to be wary of. Banks might say they care about moving dirty cash, but in reality they care about losing money. And once you look at the problems created by the post-9/11 financial architecture from that perspective, everything makes sense.

In short, banks have been asked to take on a policing role, but they’re refusing to do it. Why? Because it’s expensive. One European bank told researchers for the Norwegian Refugee Council that 40 or 50 employees were required to check just one client’s attempt to send funds to Afghanistan. How long would any business keep doing that before deciding that it’s not worth their while? If maintaining one bank account requires the services of dozens of compliance officers and bears the risk of a billion-dollar fine if money leaks out to the wrong recipient, it is entirely rational to shut it down. “We are kind of in a ping-pong match between financial inclusion and avoiding regulatory scrutiny, and we are the ball,” said Pamela Dearden, managing director for financial crimes enforcement at JPMorgan Chase.

Between 2016 and 2022, the number of accounts being closed annually in the UK rose from 45,091 to 343,350, and I suspect other countries will show a similar pattern. I’m sure bankers don’t take these decisions lightly, but their priority remains the bank, not its customers.

A British parliamentary report quoted a small company that built solar-powered water pumps in India for customers in Africa, with support from the UK and US governments. In 2020, its bank said it would be closing the company’s account. The company received no explanation, but its leaders suspected the bank’s suspicions originated from the fact it was receiving funds from Nigeria, which is considered risky for both money laundering and terrorism reasons. They wanted to explain the misunderstanding, but that proved nearly impossible. “It was like dealing with a black hole. The bank didn’t want to listen and, seemingly, didn’t care,” the report quoted the company’s chief executive as saying. “It felt very automatic. Computer says no. It was a very scary time.”

When prospective replacement banks heard why the company needed a new account, they naturally refused to provide one. Eventually, in desperation, the company’s chief executive asked his MP to contact the bank’s chief executive, who abruptly – and again without explanation – reversed the decision, and allowed the account to stay open.

The situation feels completely capricious, with decisions made by anonymous compliance officers on the basis of unknown information, unless you’re lucky enough to find someone who can reverse the decisions, again with no apparent logic behind it.

It hardly needs saying, but this post-9/11 system has not achieved its goals. Not only did the campaign to deprive terrorists of financial support fail to stop them, but militant groups have spread across much of the Middle East, central Africa and elsewhere. The Taliban are back in control of Afghanistan.

For years, campaigners have sought to explain to politicians that the system they’ve created is causing a huge amount of damage, without doing much good. Interventions by the FATF have failed, not because they’re not well intentioned, but because they don’t get to the heart of the problem.

This is, above all, a political failure. Because banks operate for profit, asking them to be a police force is inherently corrupting. There’s a reason that civilised countries don’t use bounty hunters. If the bounty is too low, the crime won’t be solved; and if a defendant is rich, he’ll buy his freedom and the crime won’t be solved either. By asking banks to police terrorist financing, we end up harming the poorest people because they can’t pay off their own bounties, and letting off the richest ones, because they can. Banks get fined if they’re caught breaking the rules, but that just means they ensure their fees are sufficient to fill the hole.

And unlike a proper criminal justice system, there is no appeal against the banks’ decisions. Some debanked people have tried to sue their banks for discrimination, and there have been isolated examples of them winning small amounts of compensation. But in general, banks have no obligation to keep providing a customer with a bank account. As long as they comply with the terms of their customers’ contracts, they can do what they like.

For those who lose their bank account, there is one option still open, however. The catch is that it’s only available to a select few.

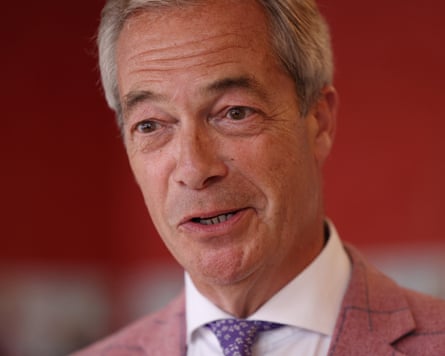

In November 2022, the “wealth reputational risk committee” of Coutts, a private bank in the UK that provides services only to very wealthy customers, decided to debank Nigel Farage. According to internal documents, the bank made the decision because Farage was a “significantly loss-making” client, but it also took into account that some of his more divisive political positions might threaten the bank’s reputation.

Farage did not take this decision well. In June 2023, he revealed what had happened, and accused the bank of punishing him for his political beliefs – something the bank struggled to deny, since the documents he obtained did indeed show they had considered his politics while making their decision.

Farage’s friends in the media and in politics spun this as a financial version of “cancel culture” and eventually forced Coutts to reverse its decision. It was a telling episode. Politicians and journalists presented this as an isolated and troubling incident that demanded immediate political intervention. It seemed that they were entirely unaware of how normal it is for banks to close customers’ accounts because of who they are. What happened to Farage was exactly what had been happening to British Muslims for decades. The difference was that he had high-profile allies who had questions asked about him in the House of Commons and articles written about him in the press which embarrassed his bankers into changing their minds.

A similar episode occurred in the US after the Treasury Department in 2013 launched an anti-fraud campaign called Operation Choke Point. After a series of high-profile financial scandals – particularly the Bernie Madoff and Allen Stanford pyramid schemes – officials were looking to find ways to stop banks moving the proceeds of fraud. They decided to target “choke points” in the financial system, and particularly the payment processors that handle transactions for merchants. It was entirely in line with decades of anti-money-laundering practice, but it had the misfortune to be opposed by some lobbyists working for banks, and to have been given a sinister name.

Those lobbyists, in looking for a way to oppose the operation, found a document laying out the categories of client that bankers should consider to be high risk. Most of the list was understandable – people running escort services or Ponzi schemes, for instance – but it also included “firearms and ammunition manufacturers and retailers”, and that was their opportunity. Campaigners presented the operation as a political assault by Barack Obama’s White House on the constitutional right to bear arms. “Operation Choke Point is an affront to the freedoms and liberty that millions of Americans have died to protect,” insisted Texas congressman Roger Williams. It was, he continued, “one of the most abusive government overreaches in our nation’s history”. Administration officials and media commentators tried to explain that the operation was completely normal, that no gun shops had been involved, that banks were just being asked to conduct their usual risk-based assessments. It didn’t matter. The operation was cancelled in 2015.

The success of the opposition to Choke Point, however, ensured that when cryptocurrency companies lost their bank accounts, their advocates decided to use the same tactics against Joe Biden’s administration. This was Choke Point 2.0, they said. The White House was seeking to use administrative back channels to protect banks from competition. This was nonsense. There were good reasons to be concerned that crypto companies were facilitating money laundering and fraud, since so many of them had done precisely that. Nonetheless, the idea that this was a politically motivated hit spread in the rightwing media until it became a widely held belief.

“Basically, it’s a privatised sanctions regime that lets bureaucrats do to American citizens the same thing that we do to Iran,” said Marc Andreessen, a billionaire software engineer turned venture capitalist who became a vocal campaigner for Donald Trump’s 2024 reelection campaign, on the Joe Rogan podcast in November that year. “This has been happening to a lot of the fintech entrepreneurs, anybody trying to start any new kind of banking service because they’re trying to protect the big banks.”

The way Andreessen explained it, the US Treasury secretary could just phone up a bank and demand that a political opponent be kicked out of the financial system, which explained why – according to him – only conservatives suffered.

“So no one on the left gets debanked?” asked Rogan.

“I have not heard of a single instance of anyone on the left getting debanked,” replied Andreessen.

I loathe the tendency of wealthy, well-connected rightwingers to present themselves as victims, rather than as the spectacularly fortunate people they really are. It is cynical, annoying and misleading, and Andreessen’s explanation of how banks assess whether a client is politically exposed was either wildly ill-informed or deliberately wrong.

However, despite myself, I am sympathetic to the arguments they’ve made around debanking. The reason that the defenders of Operation Choke Point, or indeed Coutts bank, struggled to mount a convincing defence of what they’d done is that the critics were right. It genuinely is sinister that anyone can be debanked simply because bankers consider them to be too expensive or risky to be worth the trouble. What is even more sinister, however, is that the only people who can get a fair hearing if they lose their bank accounts are those sufficiently well connected, rich or media savvy to make a successful fuss about it.

This an adapted extract from Everybody Loves Our Dollars: How Money Laundering Won by Oliver Bullough, published by W&N on 29 January

3 weeks ago

28

3 weeks ago

28