Whether it’s literally bringing Panamanian soil to Miami, or subverting the messages of Mexican religious cults by appropriating their iconography into tile murals dripping with sexual innuendo, Latin American artists at Art Basel Miami Beach this year are finding ways to reinvent their cultural heritage as surprising and fantastic pieces of art.

The Mexican artist Renata Petersen, originally from Guadalajara, has outfitted her Art Basel booth with three collections that may at first appear disconnected – intricate murals made from tiles and covered slogans and iconography, 80 chrome-blown glass works that look slightly like chess pieces but are actually derived from sex toys, and ceramic vases sporting carefully arranged motifs. For Petersen, these works spring from a childhood lived with her anthropologist mother, where she learned to look at cults and other religious movements with a detached eye.

“My mom is an anthropologist and specializes in religion, and she took me along to all of her fieldwork,” Petersen shared. “She has a book that she wrote in 1993, The Kids of the Light, about a huge cult that started in Guadalajara. My life story was really influenced through my mom’s story, always asking questions, never judging, just very open to understanding these new religious movements.”

Petersen is partly motivated by preserving the history of these subcultures. “These were real people,” she said. “They were real lives, and anyway, they’re still here – you could always end up being in a cult.” She’s also fascinated by how humans are able to take something as abstract as the sacred and make it very corporeal. It was that drive to make the divine concrete that brought her to the blown-glass artisans of Jalisco, Mexico, where she found inspiration for her own glass creations. “They’re somewhere between stupas and butt plugs,” she said, referencing Buddhist monuments in the same breath as sex toys, “they are temples to our sexual drive.”

Hailing from São Paulo, artist Thalita Hamaoui also draws on national traditions, although for her the results are not tiles and sculptures but rather striking oil paintings that dance with movement and dazzle with contrasting colors. Inspired by the Impressionists, Hamaoui’s Brazilian landscapes are more imaginary conjurings of the experience of being in Brazil than straight depictions of landscapes one might actually see. “I’m looking for an instant of a landscape, it’s like a second or something,” she told me. “In Brazil you can have so many different kinds of weather in the same day, it’s all so much.”

Hamaoiu draws from non-western artistic traditions to eschew a vanishing point and instead flatten out her landscapes, producing a sensuous and eye-catching melange of intricately layered texture and color. Hamaoiu works surrounded by her multiple canvasses, which she intuitively moves between during a creative session, alternatively zeroing in on a small dab of paint, then stepping back to assess the work as whole.

“When I’m in the studio I can take my time with things, and that’s so beautiful and so incredible – to be able to linger over the little things,” she shared. “São Paulo is crazy, and when I go into the studio and the time is so slow. Oil paint isn’t something that you can hurry, it takes months to dry.”

Growing up in the 1980s as Brazil was emerging from a nearly 30-year dictatorship, art was not the most lucrative choice for Hamaoui to choose for her career. “Brazil wasn’t a place where you could be an artist,” she told me. “It was like, ‘Well, I’m going to be fucked for sure.’” She made her way by customizing secondhand clothes, often painting directly on to them, a skill which came in handy as she eventually transitioned to painting on to cotton and linen. “Even today, when I paint I really like to very carefully choose the fabrics that I use. It makes such a difference in the surface, if you use linen or cotton.”

From Brazil’s neighbor to the south, Argentinian Gabriel Chaile makes formidable adobe sculptures, a material that takes him back to his childhood hearth – it was there his family made the bread that is typically sold in the north of Argentina in order to sustain the household. The recipe for the bread came from Chaile’s Indigenous grandmother, who had originally shown her household how to provide for itself through baking.

Chaile shapes his adobe into vaguely hearth-like, mysterious forms covered in innumerable markings, shapes that feel drawn from the archaic history of visual culture and that point to a shared humanity that transcends national divisions. “Studying art, that is, studying images,” he shared in Spanish, “enables me more and more to observe these forms of all of ‘America’ with a certain brotherhood.”

From time-worn forms to the present day, Chaile’s adobe sculptures are joined by drawings and photos inspired by the No Kings Day protests, which he happened to see during a residency in Bozeman, Montana. Chaile mused that he had never seen a protest like that before – one where the slogans and signs were primarily directed at passing cars – and it became for him a moment of union among far-flung groups of people.

“What really inspired me was the feeling I had while watching that protest,” he said. “I wasn’t thinking about Trump, which is to say, I didn’t think about the idea of the other as an enemy. I was thinking about the gesture that this group of human beings was making when they came together to fight to maintain a true coexistence between all the different groups that can come together to make a society. This was what struck me.”

Panamanian Cisco Merel has brought, as he puts it, “immigrants” to Miami from his native country – that is, soil mixed with resin that he combined with mud from Miami into a beautiful wall covering for his Art Basel booth. “The idea is take the soil from Panama and the soil from Miami,” he said, “to try to bring us together.”

Soil is a material that has deep roots for Merel, as it is central to the Junta de Embarra, a tradition in which a Panamanian community comes together to build a house, often in a single day. “If you need to build a house, everyone is invited and you build the house in one day,” he said. “Some people bring beer, others food, others soil, everything, it’s like a community ritual.” In learning to work with soil, Merel traveled all over Panama, interviewing elders who could inform him of these age-old practices.

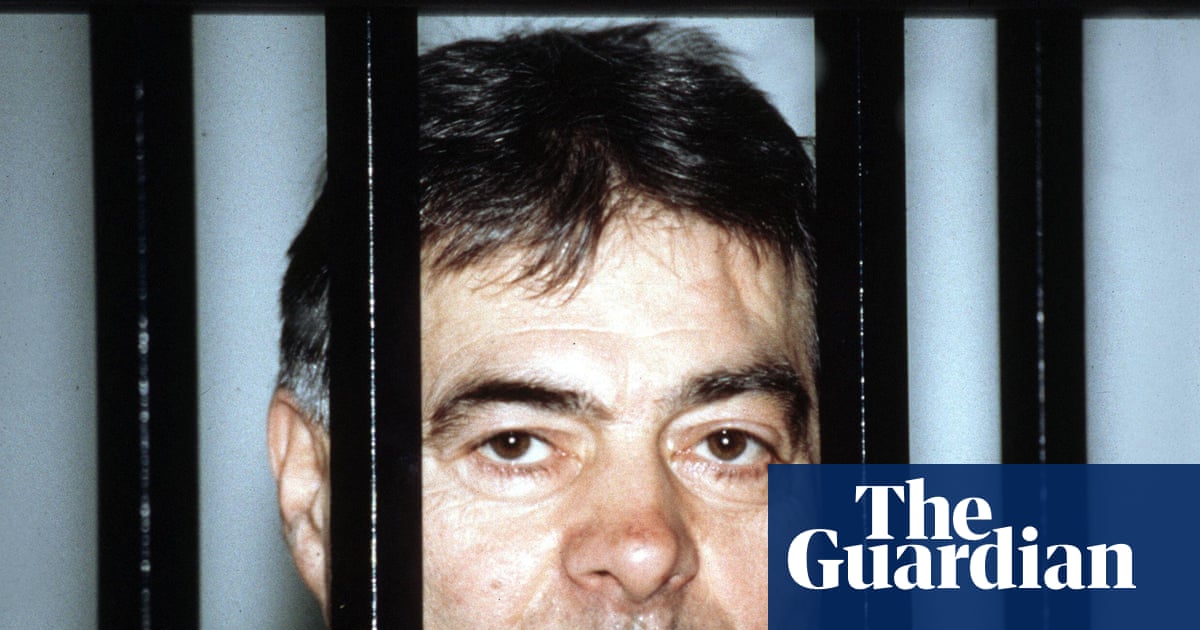

Merel’s booth is filled out with bright, sleek abstract paintings of what he calls “impossible structures”. They are in part inspired by his take on Panamanian society itself, which somehow manages to keep going on. “In Panama everything is built, but nobody knows how it’s working, it’s very mysterious,” Merel said. “Everything is on the edge, at the extremes. Other countries say, ‘Panama is doing so well!’ but no, I think it’s actually really complicated.”

2 months ago

55

2 months ago

55