When Zohran Mamdani sailed to a surprising but decisive victory in New York City’s Democratic mayoral primary last month, he did so propelled by a platform laser-focused on making the country’s largest city more affordable for working people. Among his proposed policies for achieving that vision – which include free childcare and a rent freeze for tenants – is the proposal to create a network of city-owned grocery stores focused on keeping food prices low rather than on making a profit.

“Without having to pay rent or property taxes, they will reduce overhead and pass on savings to shoppers,” Mamdani said on his website. “They will buy and sell at wholesale prices, centralize warehousing and distribution, and partner with local neighborhoods on products and sourcing.”

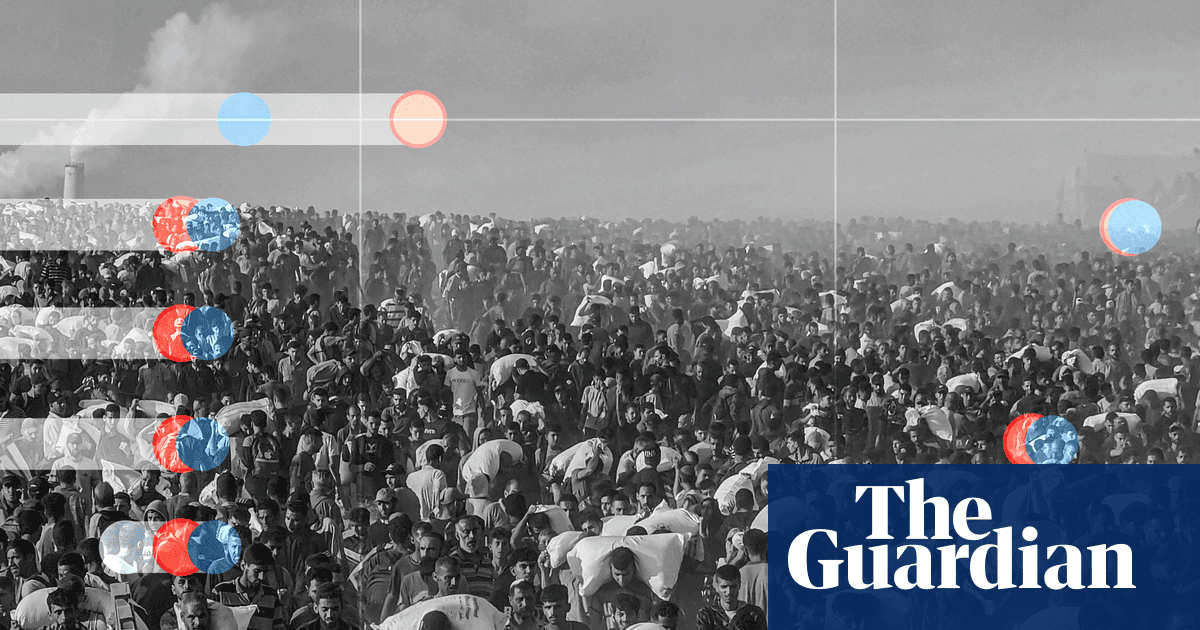

The proposal seems to be resonating. Two-thirds of New Yorkers polled said they support the creation of municipal grocery stores, according to an April 2025 report published by the Climate & Community Institute and Data for Progress. Another 85% said they were paying more for groceries this year than last, and 91% were concerned about how inflation is affecting food costs. (While inflation is one factor contributing to sticker shock at the cash register, US food companies’ profits have soared as they have continued to raise prices faster than both inflation and wage increases.)

“From 2020 to 2024, the food consumer price index rose 23.6%, so we already know working-class families spend a much larger percentage of their household monthly income on food than middle- and upper-class families,” said Justin Myers, an associate professor at California State University, Fresno whose past research has investigated public grocery stores. Plus, he said, “the average cost of groceries in New York City is 18% higher than the national average.”

But could city-owned grocery stores really lower the cost of food? According to many experts, the idea isn’t as out there as it might seem.

The history of government-funded food infrastructure

While Mamdani’s proposal might feel novel, there’s plenty of precedent for state-supported food infrastructure.

According to Anna Chworow, deputy director of the UK-based non-profit Nourish Scotland, the 20th century was full of these kinds of initiatives: wartime Britain had “British restaurants”, a chain of over 2,000 restaurants that served price-capped meals, and Poland had “milk bars”, subsidized cafeterias where meals cost two-thirds or half of what they might at a traditional restaurant. Similar establishments are starting to pop up today in India, Turkey, Indonesia, China, Mexico and Brazil, said Chworow, whose organization put out a recent report on the subject.

These kinds of establishments have often been very well-received by the communities they serve. One operator of a milk bar in Warsaw told Chworow of a community that, upon hearing that their local milk bar would no longer be funded by the government, staged a protest by taking over the kitchen. “There was a real sense of civic activism around keeping that place open,” Chworow said.

Closer to home, “public options have been part of the fabric of this nation since its founding, between the postal service, public libraries, and public parks,” said Margaret Mullins, director of public options and governance at the Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator. In fact, NYC already has six grocery stores that enjoy government support in the form of steep rent discounts, including Essex Street Market on the Lower East Side, through the city’s Economic Development Corporation. “Sometimes in places where the private market won’t step in, the public can and should,” Mullins said.

Contemporary parallels

Across the country, many municipalities have done the same. Big cities like Madison, Wisconsin, and Atlanta, Georgia, are currently exploring ways to use city support to address food deserts, while small towns in Kansas and Florida have turned to town-owned grocery stores after privately owned grocers have shut down or left.

These initiatives often begin when a community has already been failed by the private sector. Atlanta councilmember Marci Overstreet knows firsthand what it’s like when a community is left completely at the mercy of private grocery stores. As councilmember of a district with limited access to fresh food, Overstreet began doing everything she could to lure grocery developers to her area, attending trade shows in Vegas and setting up meetings with big-box grocers. Time and again, she watched as store representatives would punch in her zip code and disqualify her district on the spot for not being deemed a profitable enough area to be worth opening a store in.

“Finally, we had to say, ‘You know what, no one’s coming. Cavalry is not coming. We’re going to have to take care of this ourselves,’” Overstreet said. Overstreet spent eight years trying to solve the grocery problem in her district, which included spearheading partnerships with public schools and local churches where people could pick up food.

Today, she’s proud to be bringing a new, full-size grocery store to her district with the backing of Invest Atlanta, the official economic development authority of the city, in partnership with Savi Provisions, a specialty private grocer. The resulting public-private partnership isn’t an exact parallel for the municipally owned stores that Mamdani has proposed for New York, but it’s a reminder that when the private market left to its own devices is failing a community, government officials can find creative ways to step in.

As much as New York might learn from looking to other cities, some experts say there’s even better proof that government-owned grocery stores can work to be found in a surprising place: the US military.

Every branch of the military has its own public grocery system, sometimes referred to as an exchange or commissary, that allows military families to buy groceries on military bases at significantly lower prices than what civilians can get from traditional grocers. “Military families buy groceries for 30 to 40% cheaper than what grocery stores in the area sell, simply because they’re not taking a full wholesale and retail markup like a lot of stores are,” said Errol Schweitzer, a grocery store veteran and former VP at Whole Foods, who has written about the commissary model before.

According to Bill Moore, the former director and CEO of the Defense Commissary Agency, the commissary system saved military families approximately $1.58bn in 2023.

Passing along similar benefits to civilians is quite possible, according to Schweitzer. “It’s not a radical proposal,” he said. “There already is heavy government intervention in the food system every day.”

How to make government-owned grocery stores successful

So what would it take practically to make Mamdani’s proposal work in NYC?

According to Overstreet, the councilmember from Atlanta, community buy-in is key. In her district, Overstreet sought feedback about what kinds of products community members wanted access to, down to the preferred variety of apple. Overstreet and her team did this through roundtables, pop-up meetings, and both paper and online questionnaires to try to reach the widest array of people.

Chworow, who researched public food infrastructure over the last century, said that creating a universally useful resource – not one that just serves targeted groups, like low-income families – is also crucial.

“As soon as you start to target the interventions, there’s a level of stigma that comes around it, and people are reluctant to use them because they don’t want to be associated with the stigmatized group,” Chworow said. “Promoting it as a universal service removes those barriers, and it also oftentimes makes the economic model better.”

Some of how military commissaries – and grocers like Walmart, for that matter – deliver low prices is through economies of scale, using their size and buying power as a network to negotiate lower prices with wholesalers. That could pose a problem to Mamdani’s plan, as he’s proposed opening just five municipal grocery stores total, one for each borough. But Schweitzer pointed out that the city already buys extraordinary amounts of food for public schools, hospitals and community colleges; by linking the grocery stores to those existing agreements, he noted, they might likewise take advantage of economies of scale that would otherwise be out of reach.

Schweitzer, who has written extensively about how to make a public grocery sector work, also recommends looking to successful grocery store chains for cues. Operating like Aldi (which is to say, opening lots of smaller stores with a limited assortment) or Costco (which is to say, operating as a warehouse store; “literally a distributor that sells to the public”), he said, could help make municipal grocery stores a success.

Lastly, noted Caruso, it was worth reminding community members that such an initiative will take time to realize. Overstreet noted that it took her eight years of work to get the new grocery store in her district under way.

The historical precedent, efforts in other cities, and parallels with the US commissary system of course don’t prove that New York’s attempts will be successful. Municipal grocery stores will have to battle many of the same problems that have sunk hundreds of private grocery stores in the city in recent years.

But these examples do provide ample evidence that government-run food infrastructure can work, given the right support and proper management.

“It’s not to say that anything is easy, but of course it can be done,” said Mullins. “Just look at these other public options – the post office, public libraries, public schools. These are great things that have been critical parts of communities for a very long time.”

3 months ago

38

3 months ago

38