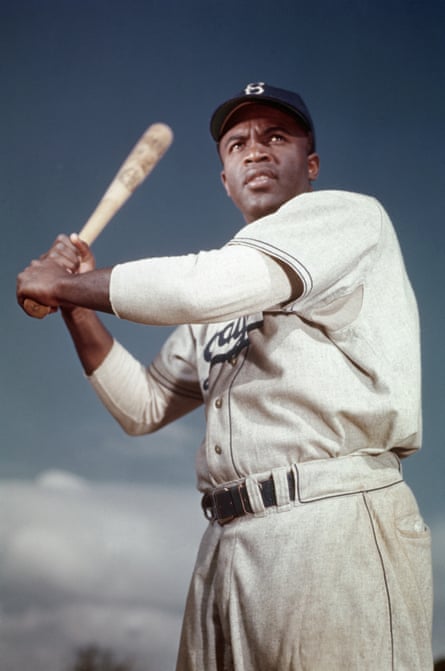

Everyone from Jackie Robinson’s home town has a story about the baseball legend. Stick around long enough in his southern California neighborhood and Jackie’s name will bubble up in a story about a distant relative who once struck out the future Hall of Famer on a dusty field that now bears his name. Over the years, these stories gather layers – part memory, part myth – until they sound like hometown folklore.

George Ito was one of those storytellers. A second-generation Japanese American who grew up in Pasadena, California, a few doors down from the Robinson family, George loved to remind his children about his friendship with Jackie. On jogs with his son, Steven Ito, he would rattle off tales of all the times he outran his legendary friend.

“Did I ever tell you about the time I beat Jackie Robinson in a tennis match?” he’d ask.

“Many times,” Steven would reply, his voice dripping with skepticism.

In 1986, at George’s funeral, members of the Robinson family made a surprise appearance. The gesture revealed what George’s stories only hinted at: the Robinson and the Ito families were more than one-time neighbors – they were lifelong friends. Through the Great Depression and the second world war, when Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes for incarceration camps, the Robinsons stood by their side.

Turns out, George’s stories were true, said Steven, 77. Many Japanese Americans from Pasadena have similar stories about the Robinsons. They were the kind of family that showed generosity and neighborliness.

Before Jackie made history for breaking the racial barrier in Major League Baseball and cemented himself as a sports icon, he and his older brother Mack Robinson formed deep bonds with Japanese American families – a legacy forged in an era of restrictive housing covenants. That quiet solidarity, some say, is as enduring as Jackie’s home-run legacy.

“That was the essence of the Robinsons,” said Edward Robinson, 58, Mack’s son. “We looked into the community and tried to always uplift.”

‘Baseball was their glue’

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, fear and suspicion swept across the US as the government ordered the incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. Many residents thought it was an unjust act, said Susie Ling, an associate professor of history and Asian American studies at Pasadena City College. There are many documented cases of people who during this time asked themselves: what can I do to help my friend?

Few of those stories, however, involved world-class athletes.

The Pasadena of Mack and Jackie’s youth was a multicultural enclave, said Wayne Robinson, 68, Mack’s son. Especially in parts of north-west Pasadena, where racially restrictive housing covenants confined most residents of color. This is where the Robinsons put down roots in 1922. Their home at 121 Pepper Street anchored a tight-knit block.

A little over two miles away, Shigeo “Shig” Takayama lived at 310 Green Street. Shig, a second-generation Japanese American, often walked home from school with Jackie and his siblings, said Joan Takayama-Ogawa, Shig’s niece. For an after-school snack, they collected free misshapen potato chips from a nearby factory.

During the war, while Shig and his older brother served in the US military, their father, Shichitaro Takayama, was incarcerated at Gila River in Arizona. In the family’s absence, neighbors including the Robinson family helped care for the Takayama home. Facing mass incarceration, many Japanese American families turned to their neighbors to help safeguard their properties. Many were betrayed. Hasty promises were broken. Some properties were robbed or vandalized.

In Pasadena, the Takayama home remained pristine.

“It was as if they walked out one day and then after world war two, came back home,” said Takayama-Ogawa, 70. She credits the Robinsons and other neighbors who stepped in to care for the property during the family’s forced absence.

Shig and Jackie’s friendship was forged out of the love of baseball. They played on the same high school team and again at Pasadena Junior College (now called Pasadena City College), where Shig – a scrappy third baseman just over five feet tall – stayed an extra year just to share the field with his friend.

“I was just lucky to play with him,” said Shig about Jackie in a 2003 interview. “I really enjoyed him. He was really a nice person.”

Despite his small stature, Shig could hit with power and run with speed, said Kerry Yo Nakagawa, founder of the Nisei Baseball Research Project.

“Baseball was their glue,” said Nakagawa, 70, about Shig and Jackie.

The families’ friendship created cultural transmissions – especially through food. For years, the Takayama family ate black-eyed peas and collard greens on top of white rice.

“To me, that tells me more about the relationships and community relationships than anything,” said Takayama-Ogawa.

That solidarity extended beyond Pasadena. In 1937, while traveling with the team for a baseball game in Fresno, Shig and Jackie were denied hotel rooms because of their race. The hotel staff set up two cots in a broom closet instead.

after newsletter promotion

The two friends bunked side-by-side, then got up the next morning and played ball.

‘You would defend your friends. That’s all you had’

On Pepper Street, the neighborhood kids formed a tight-knit friend group. In Jackie’s own words from his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had It Made, the group had a name – the Pepper Street Gang.

“Our gang was made up of Blacks, Japanese, and Mexican kids,” said Jackie in his book. “All of us came from poor families and had extra time on our hands.”

The ragtag group didn’t fit into the modern definition of a gang. They were just a group of neighborhood friends, said Kathy Robinson-Young, 66, Mack’s daughter.

George Ito, who lived at 273 Pepper Street, often recalled how the gang felt like a band of brothers.

After school, if the Robinson siblings were chased home by rock-throwing kids, they would run to Ito’s house and mount their defense.

The Pepper Street Gang held regular evening meetings, George told his family. Each meeting always started with a ritual: every kid would share the best thing that happened to them that day.

It almost sounds too wholesome to be true.

“That’s why it was kind of hard for me to believe when I first heard the story, right?” said Steven.

But for a group of kids of color growing up in Depression-era Pasadena, it was a deliberate act of optimism – a survival tactic disguised as a childhood routine.

“It’s a testament to what friendship really meant back then,” said Steven. “Even though you would get in the middle of this kind of hatred, it didn’t matter. You would defend your friends. That’s all you had.”

The Pepper Street Gang eventually disbanded. Most members are dead. Mack remained in Pasadena and became a tireless community advocate for youth and civil rights until he died in 2000. Jackie’s legacy, of course, towers over baseball history.

But to those who knew the Robinsons – and those whose families lived on the same block – it’s these quieter stories that reveal the fuller picture.

“There’s something wrong with the writing of our history if this story is little known,” said Ling.

Tall tales or not, these stories carry universal and timeless lessons: kind gestures can ripple across generations. Be neighborly. Stand up for your friends. Check on each other.

Small acts of humanity can change lives.

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48