Nobody wins a trade war. You can lose it by greater or lesser degrees: you may be one of the luckier casualties. But that’s about as good as it gets. So, while there will have been initial relief in Downing Street on Wednesday night, a feeling even that Keir Starmer’s placating of Donald Trump looks vindicated, what followed was no victory lap.

How could it be, after that grotesquely swaggering show trial the president staged in the White House garden, all the better to jazz up an economic assault on what were once his country’s allies? Come on down, Britain, escaping with just the minimum 10% tariff on its exports to the US and no drive-by insults! Better than Taiwan (32% plus a lecture about how the US used to build all the semiconductors once), Vietnam (“They like me, I like them” but still a brutal 46%), the EU (“very very tough traders” and lucky to get away with 20%) or poor Lesotho, still reeling from the overnight collapse of US aid and now whacked by a 50% tariff. But even lucky Britain still emerged with a 25% duty on cars that the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) estimates could cost 25,000 jobs, plus the grim realisation that this may be just the beginning of a long unravelling. Globalisation is dead, protectionism is back, and all to satisfy one man’s delusions that life was better in the 1800s before income tax was invented.

Ministers’ first worry will be about dumping – countries flooding Britain with cheap stuff they can no longer shift to the US, which is lethal for domestic producers – and the future of manufacturing jobs, many clustered in Labour seats. But beyond that lies the dismal prospect of more tax rises and spending cuts, given what this may do to already stuttering hopes of growth.

Stock markets tumbled worldwide but Trump seems past caring about that, or even about how ordinary Americans will react to the now inevitable price rises at home – not just on imported brands but on American-made ones involving foreign components. Instead, the president seems caught up in his own spectacle: the suspense stoked by refusing to brief friendly governments in advance, the made-for-TV drama of bringing a retired car-plant worker onstage to hail the supposed return of manufacturing to Detroit, the plot twists as he escalates or retreats. As Canada and Mexico have discovered, Trump can lift tariffs unexpectedly quickly but then just as suddenly come back for more, and the fact they had trade deals with the US did not protect them. Now we’re all strapped to the same mad rollercoaster.

It could be a long ride. Buried in that rambling speech was a tacit admission that tariffs abroad are raising funds for big tax cuts at home. That suggests Britons may end up paying with their jobs and prosperity for already wealthy Americans – those who can absorb higher prices now, and who don’t lose their jobs amid the unwinding of global supply chains – to get richer. Some special relationship that is. But it also implies that Trump will keep pushing the tariff button until the coffers are full enough, an outcome over which Britain has minimal influence. (We may have escaped relatively lightly this time less because of our Trump-whispering skills – other countries who tried buttering him up weren’t spared – than by being a service-based economy whose balanced trade with the US put us on the right side of a crude mathematical ledger.) Where political judgment could, however, make a difference is closer to home, as the various crises triggered by Trump start converging with each other.

The business secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, avoided denying this morning that he is considering nationalising British Steel, badly hit by a separate Trump tariff on steel. But that it’s even being considered is a sign of the times: defence manufacturing relies on steel, and a country forced into rapidly rearming will need a secure supply.

Britain’s proposed trade deal, meanwhile, risks getting tangled up in a culture war pursued by JD Vance and other key White House figures, seeking to impose their values – unfettered free speech, militant Christianity, deep suspicion of any regulation restricting profits – on a resistant Europe.

This week it emerged that US government officials are “monitoring” the seemingly obscure British case of the anti-abortion protester Livia Tossici-Bolt, who is challenging a fixed-penalty notice for allegedly breaching the legal buffer zone around a Bournemouth abortion clinic (designed to protect women being intimidated when seeking treatment). Washington is, apparently, “concerned about freedom of expression” in Britain. Though Reynolds stressed the case wasn’t raised in trade talks, the timing doesn’t seem wholly irrelevant.

Nor does the fact that US officials have challenged the British regulator Ofcom about new laws on online social harms, aimed at removing illegal material and protecting children from harmful content. A chronically online White House seems to be trying to force itself not just into a debate over the tax treatment of American tech giants, but over the toxic effects of social media platforms on our everyday lives. If Brits don’t want to stew in an angry, poisonous, fake-news-addled information ecosystem any more than we want to eat chlorine-washed American chicken, that should be our sovereign choice. But will it?

Starmer’s main aim for now is characteristically to sit tight and say little. There will be no instant retaliation, just weeks of consultation on what one may look like if it happened, and no revoking of Trump’s state visit. The government will push doggedly to get that trade deal signed, no matter how limited the protection it offers. Starmer will try to drain some drama from the situation, refocus on May’s local elections – though arguing about potholes and bin collections feels mildly surreal now – and quietly identify any small opportunities arising from this latest crisis.

Maybe Britain could benefit from a brain drain of talent across the Atlantic, as scientists and investors spooked by American political instability and arbitrary cuts to research grants seek to leave. Maybe, as the IPPR argues, now is the time for Britain to go all in on electric car production.

But this May’s summit with the EU now looks more crucial than ever in determining whether this crisis draws us closer to Europe or pushes us further apart. British and American fates are still very intimately entwined. But this president has knowingly upended first our security, then our prosperity. With friends like that, who needs enemies?

-

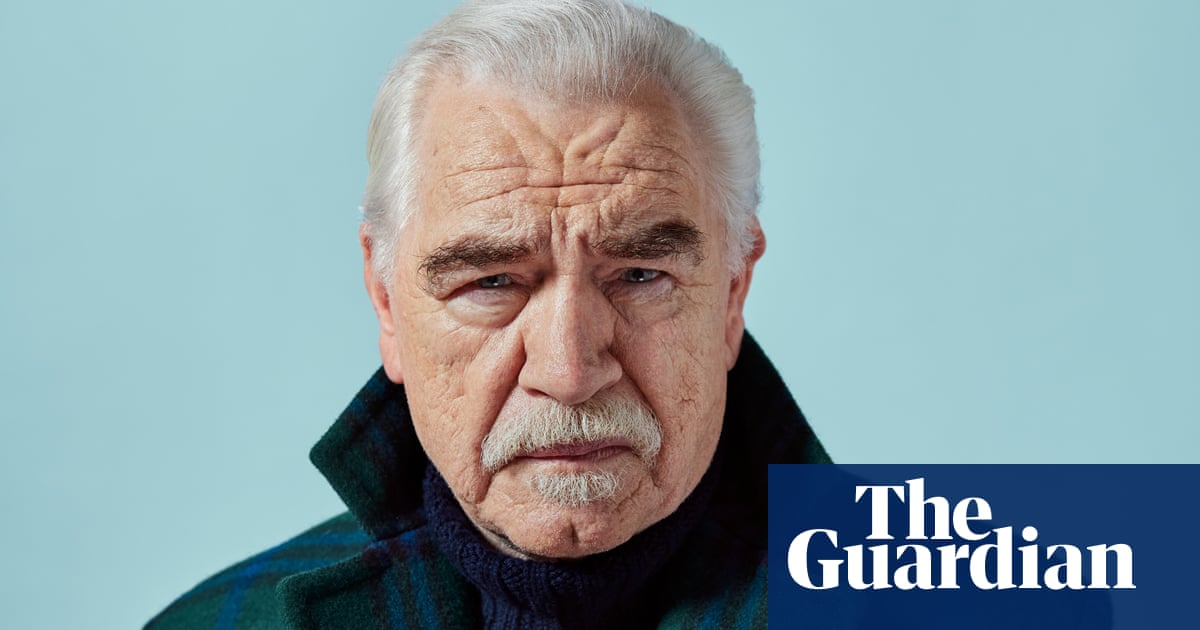

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist

-

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

18 hours ago

5

18 hours ago

5