You can practically smell the stale cigarette smoke lingering in the air of the fake motel set for Bug. It’s the play’s only location – though it appears in a distinctive second guise in the second act – and in its staging at the Samuel J Friedman Theatre, the set comes to a corner in the center of the stage, jutting out toward the audience. The additional angle gives the room a little more depth, but it also distorts the room’s geography, rendering it neither proscenium neat nor fully realistic. That’s the increasingly hard-to-recognize world that Agnes (Carrie Coon) inhabits when she brings near-stranger Peter (Namir Smallwood) into her life.

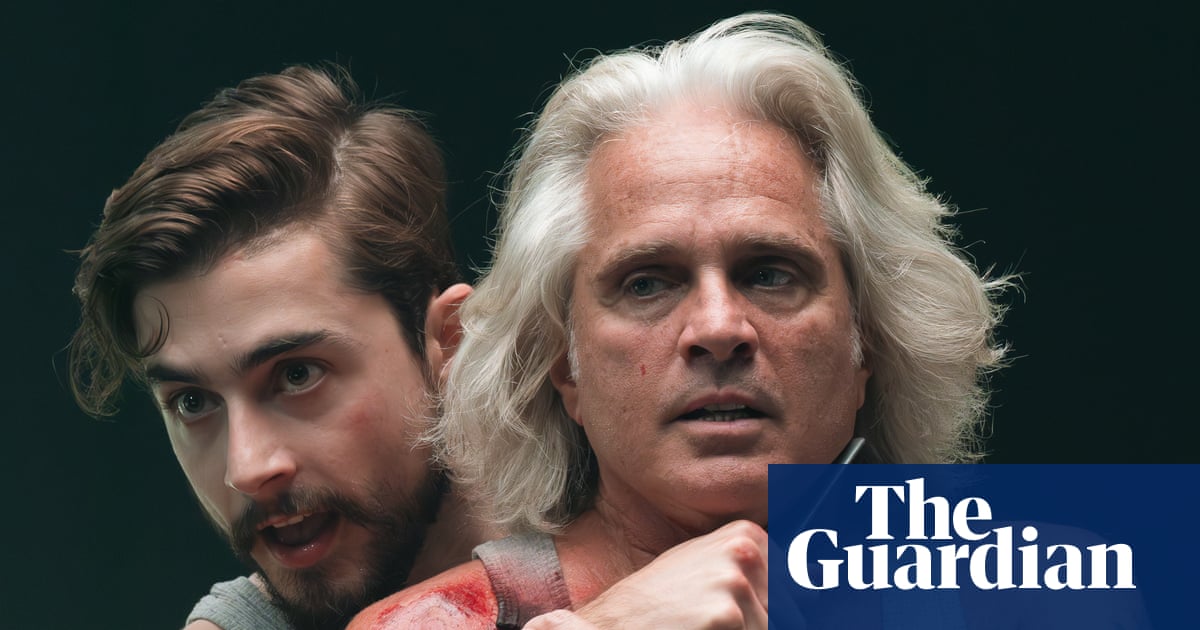

Agnes is a waitress living out of the motel, drinking and taking drugs in between shifts. Her abusive ex, Jerry (Steve Key), just out of prison, lurks around, expecting Agnes to welcome him back to their “home” whenever he pleases. So when her friend RC (Jennifer Engstrom) introduces Agnes to the drifter and supposed veteran Peter, he can’t help but seem gentler by comparison. But when Peter thinks he notices a bug bite from their shared motel bed, he starts to spiral further into paranoia. Agnes, whether aided by drugs, love, grief over her lost child or a combination of those, spirals right along with him.

This play by Tracy Letts – Coon’s spouse in real life – was initially produced in 1996 in London; revised for American shows in the early 2000s, including a year Off Broadway; and adapted into a 2006 feature film starring Michael Shannon as Peter (who originated the role in London and reprised it in several subsequent productions) and Ashley Judd as Agnes. So it’s a little odd that this first version on Broadway also purports (at least according to the Playbill) to be taking place in the present day, raising questions about what a new production of Bug has to offer in 2025.

The answers are mixed, even as the production itself remains a concise and compelling piece of theater. First written nearly 30 years ago, Peter’s increasing paranoia has a lot of 90s-era touchstones, positioning him as a Gulf war veteran, rambling about the Unabomber, Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995. There’s something to be gained from recontextualizing that itchy distrust into the present day, when conspiracy theories have undergone a shift from X-Files-ready pulp entertainment to something spread with near-religious fervor across the internet. After all, is seeing a motel room covered in microscopic bugs (even when the manager insists no other rooms have reported this problem) that different from ranting about the invisible threats of vaccines? In a sense, the world has caught up with the unnerving credulity Letts was underlining so many years ago.

Yet on a purely logistical level, there’s not much effort to make Bug less of a period piece, despite the claim that it’s taking place now. Granted, that would probably require a wholesale rewrite, and anyway, there is something equally poignant and devastatingly lonely about a world where this couple can still isolate themselves and find both solace and madness in each other, sometimes naked and sometimes afraid. Coon is as open and vulnerable as she is on the TV shows that have garnered her so many additional fans. And in contrast to Shannon, an actor whose magnetism derives from the intensity of his eyes, Smallwood plays Peter as more mild-mannered at first, doing a convincing impression of just what Agnes needs. The full extent of his paranoia, causing him to endlessly scratch at his skin and examine blood droplets in a microscope, convinced he’s seeing parasites, feels all the more heartbreaking.

Audiences seeing Bug for the first time, then, may well be transfixed, albeit temporarily. Anyone familiar with an earlier production or the William Friedkin film (which introduces some ambiguities to the story’s ending) might start to wonder if maybe Agnes and Peter are ultimately a little thin as characters – if they’re worth the intensity that Coon and Smallwood invest into this production. It’s probably not fair to compare a 100-minute early work from Letts to a towering masterpiece like August: Osage County, his Broadway debut from 2007. At the same time, Letts has clearly evolved as a writer since Bug, and it’s hard not to come away from this production wondering how he might address the contemporary version of this drug-addled psychological unmooring. It’s not so much that this production of Bug is outdated; more accurately, it’s got way too much competition, on stage and off.

1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31