After decades of recovery, southern right whales are showing signs of a climate-driven decline in breeding rates, which scientists say is a “warning signal” about changes in the Southern Ocean.

After being hunted to near extinction by commercial whaling in the 19th and 20th centuries, southern right whales remained endangered in Australia.

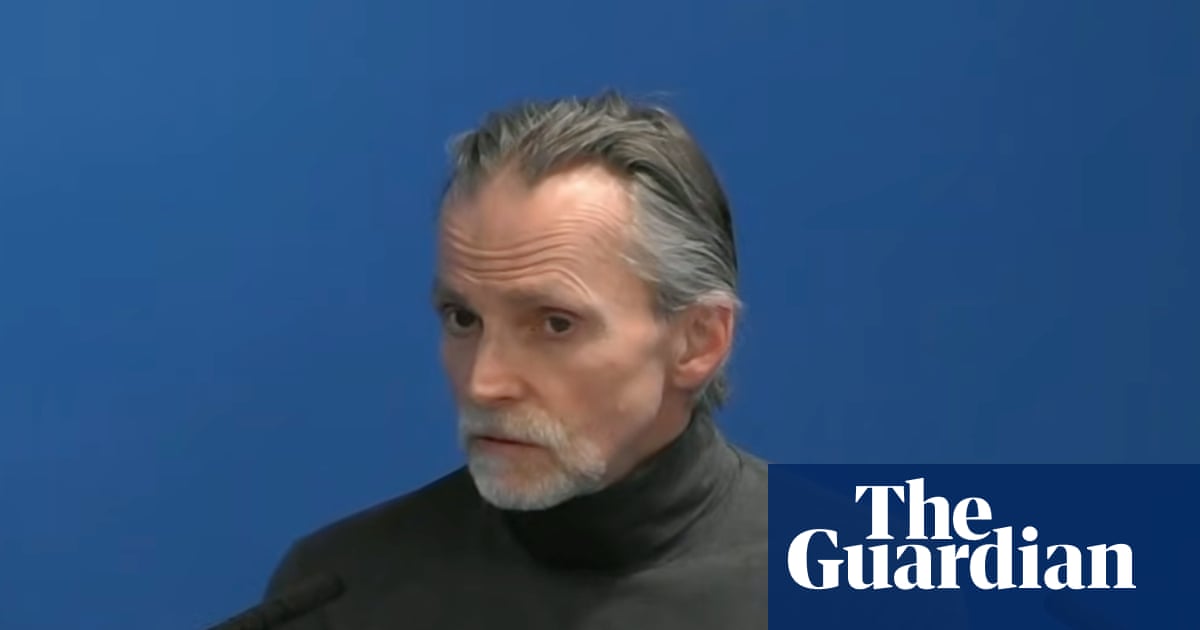

But long-term monitoring has revealed a worrying slowdown in breeding rates since 2017. Instead of giving birth to a calf every three years, southern right whales have shifted to four-year or five-year cycles, says Dr Claire Charlton, a marine biologist and the director of Current Environmental.

For more than three decades, scientists have used photo identification data collected at the Great Australian Bight to study the species, identifying individuals by unique patterns of a type of callus, called callosities, and tracking their migrations and breeding behaviour over time.

Charlton, who leads the right whale program in the Great Australian Bight, says southern right whales are “magnificent animals” – “just the sheer size of them, and the fact that they live for 150 years”.

“They feed in Antarctic and sub-Antarctic waters during our summertime, and then migrate up to our coasts during winter,” she said. “The whales come every year to breed, mate, rest and socialise.”

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

The research, published in Scientific Reports, has linked the shift in breeding cycles to climate-driven changes in their foraging grounds in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic.

“We know that the ocean is warming, the sea ice is melting, that causes other environmental changes,” said Charlton, the study’s lead author.

The paper analysed calving intervals over 35 years, revealing a correlation between breeding rates and sea ice extent, the prevalence of marine heatwaves, the availability of prey and other climate-driven changes.

The researchers said similar trends had been observed in southern right whale populations across South America and South Africa, with other krill-dependent predators also facing pressure from marine heatwaves and declining sea ice.

This was a “warning signal” about how climate change was affecting marine life, Charlton said, which highlighted the urgent need for coordinated conservation efforts.

Whale scientist Vanessa Pirotta, who was not involved with the study, said long-term data was essential for understanding these long-lived animals, and how they might adapt to a changing environment.

“We need to continue to learn more about [southern right whales] given that we were responsible for so much of their loss and where their populations are right now,” Pirotta said.

Commercial whaling ceased in Australia in 1979 and was banned by the International Whaling Commission in the late 1980s. Driven to fewer than 300 animals, populations in Australia now range between 2,346 and 3,940 individuals, or about 16% to 26% of pre-whaling levels.

Southern rights were like “tractors of the ocean”, said Dr Peter Corkeron, a marine ecologist and adjunct senior research fellow at Griffith University, who was not involved in the study. To feed, the whales would seek out dense patches of zooplankton and “go back and forth like they’re mowing the lawn”.

The change in calving intervals was a sign that conditions in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic weren’t as good as they once were, he said.

“As mammals, the choice to have a baby is demanding,” he said. “If a female wants to maximise her lifetime reproductive output, she has to balance having babies and living a long time. When conditions are getting worse, you pull back on having as many babies.”

“Anthropogenic climate disruption affects everything,” Corkeron said. “It’s just another message, if people choose to pay attention to it, that we’ve got to do something about this.”

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3