If the antibiotics we use to treat infections ever stopped working, the consequences would be catastrophic. It is estimated that the use of antibiotics adds about 20 years of life expectancy for every person worldwide (on average). As the King’s Fund put it, if we lose antibiotics, “we would lose modern medicine as we know it”. Doctors, public health experts and governments take the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) very seriously, yet the problem appears to be getting worse.

A report from the National Audit Office in February finds that out of five domestic targets set in 2019 to tackle AMR, only one has been met – to reduce antibiotic use in food-producing animals. Others, such as the target to reduce drug-resistant infections in humans by 10%, haven’t made much progress; in fact, these infections have actually increased by 13% since 2018.

AMR is often misunderstood. I have often heard people say “I’m afraid of taking antibiotics and becoming resistant to them.” But AMR isn’t about individuals becoming resistant to antibiotics. It’s about pathogens – most often bacterial infections but also viruses, fungi and parasites – evolving to become resistant to our current drugs, so that the infections they cause become untreatable. Think of ear, urinary tract and chest infections, or procedures such as C-sections and other routine surgeries, becoming life threatening because the drugs we use to treat infections or to prevent them after medical procedures don’t work.

However, I despair at Britain beating itself with yet another stick. The country has actually been fairly good at tackling AMR. In 2023, our research team led by Jay Patel published an analysis in the Lancet Infectious Diseases journal measuring the global response to AMR in 114 countries. The UK made the top three “best performing” countries with only the US and Norway ahead, followed by Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Japan. The credit in the UK largely sits with Dame Sally Davies, the chief medical officer for England from 2011 to 2019, who made it a priority during her tenure and continues to lead as the UK special envoy on AMR. The UK government has led on national guidelines and oversight in human and animal health in conjunction with the EU.

We may worry about doctors overprescribing antibiotics in the NHS, needlessly exposing pathogens to these drugs and allowing them to evolve resistance. But having worked on AMR governance before, my take is that the biggest threat is the rise of resistant pathogens emerging in countries using huge amounts of antibiotics in their animals for growth and cheap meat. Think of pigs, chickens and cattle in China, Brazil, India and, even until recently, the US. Livestock alone is estimated to consume 50% to 80% of the antibiotics produced in high- and middle-income countries. These resistant pathogens develop in animals, which are given antibiotics as a prophylactic even when they’re healthy. They then infect a human, who may travel and spread it to other humans. It is a straightforward formula. Antibiotics in animals plus farm workers plus air travel equals drug-resistant infections in the UK, and elsewhere.

It is not just theoretical. In 2018, a study in Nature found that widespread colistin-resistant bacteria, including in hospitals in London, could be traced to a single event in 2006 in China when a bacteria jumped from pigs into humans. Colistin is a last-line antibiotic for certain infections, meaning it is given after other drugs have failed, yet it was used heavily for growth promotion in pig farming in China. Since these findings, the Chinese government, as well as India and Japan, banned colistin in animal feed. This probably will have a larger impact on reducing AMR than anything being done in UK clinics and with human prescribing practices.

The UK is best protected from drug-resistant infections by working with other countries to regulate the use of antibiotics, especially in animals. Davies has tried hard to push this agenda globally, bringing together human health, agricultural and vet experts to agree on standards and regulations that are a universal good. However, there is a clear conflict with those who argue that boosting animal production, including of cheap and available meat, is the priority, especially in middle-income countries with large populations.

Why can’t we just develop new antibiotics if our current ones become ineffective? Simple question and tough answer. These are technically difficult drugs to develop and we have made very slow progress. Developing similar versions to existing antibiotics isn’t enough because they won’t be as effective against pathogens that have developed resistance: we need totally new classes of drugs. And a recent World Health Organization report noted that since 2017, while 13 new antibiotics have obtained authorisation, only two represent a new chemical class.

Our best to shot to tackle AMR is to protect our current arsenal of drugs and make sure they remain effective. This means working with other countries on a shared approach to how and when drugs are used in humans and animals. This is an ongoing challenge, especially in a world where cooperation is breaking down and isolationist approaches are on the rise. Yes, we can blame the UK government for many things, but on the issue of AMR it is a standout country and a global leader.

-

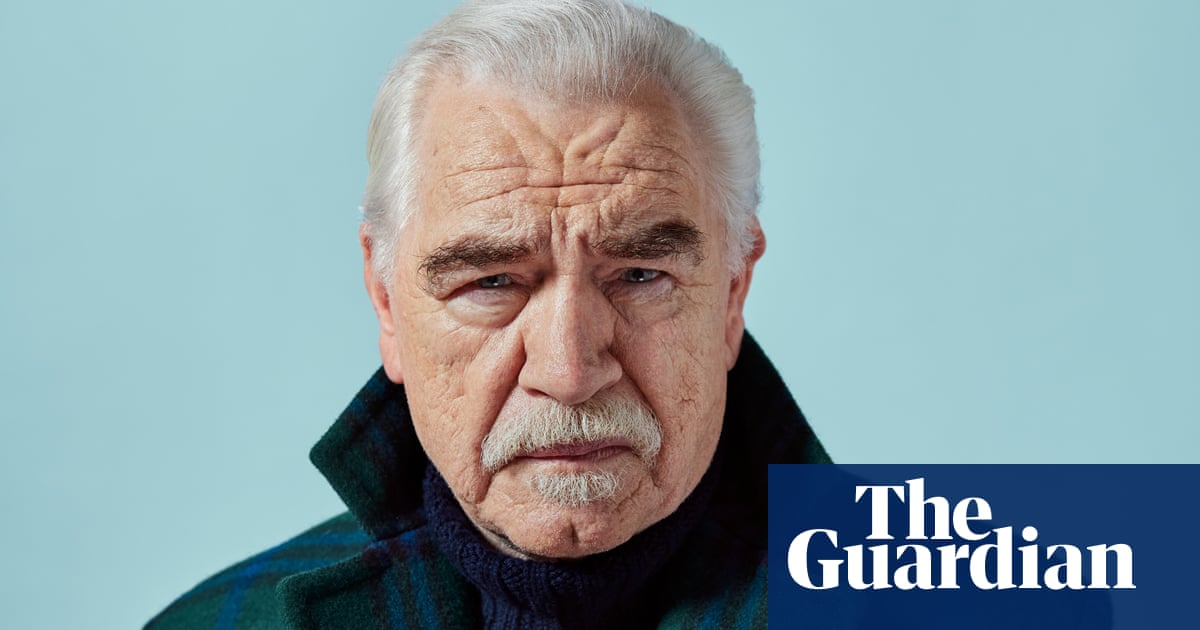

Prof Devi Sridhar is chair of global public health at the University of Edinburgh, and the author of How Not to Die (Too Soon)

23 hours ago

5

23 hours ago

5