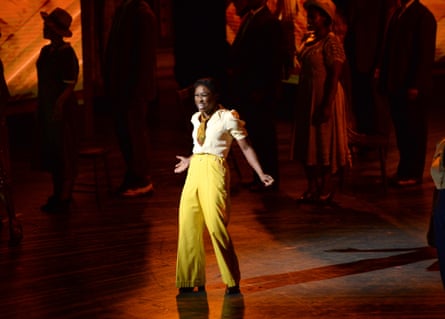

I thought I knew everything about Wicked when Cynthia Erivo walked into a meeting room in the Guardian’s London offices. She felt wildly incongruous, way too perfect and vivid for the neutral surrounds, like seeing a princess on an escalator, but I suspect she comes off like that in a lot of rooms.

Last week, Erivo received an Oscar nomination for best actress for Wicked, one of 10 nominations for the film. Released last November, within one month it had become the highest-grossing movie adaptation of a stage musical in history. Critics had been tipping it to do a double with Gladiator II, in the style of Barbenheimer the year before, with audiences seeing both in a double bill. In the event, it blew Ridley Scott’s film out of the water. Importantly, it is also astronomically magnetic to teenage girls (I have those at home), and do they ever talk.

So I knew that the braids for the wig worn by Erivo’s character, Elphaba, were made by a woman in north London, and I am not remotely surprised that, even in 5in heels, Erivo is still tiny (she is 5ft 1in without them). I know about her and her co-star Ariana Grande’s matching tattoos – “For good” on their palms, “so when we hold hands, the words touch,” Ariana told MTV in an interview; and, along with witchy hats and whatnot, hearts with letters on their ankles. Ariana’s says E for Elphaba (and Erivo), and Cynthia has a G for Glinda (and Grande).

What I didn’t know was that this role could have been written for Erivo. This is the backstory to the Wizard of Oz (for anyone who has been asleep for 100 years): the wicked witch, Elphaba, is just a very talented, young, entirely green witch, and the good witch, Glinda, is another, less talented but very popular young witch.

“I think I was surprised by how connected I felt to Elphaba,” Erivo, 38, says. “Surface, we’re different: I walk into the room, I’m bald-headed, I’ve got no eyebrows, I’ve got nails, I’ve got piercings, I’ve got tattoos, for me that’s my everyday normal but a passerby might think: ‘What is happening here?’ But as you peel away those layers, yes, I understand what it feels like to be set apart from everybody else, and not fit in; yes, I understand what it feels like to be a kid whose father doesn’t care; yes, I understand what it’s like to feel alone when you’re in a room full of people who don’t know where you’re coming from or why you’re so tired, or why you do things your way. Me and Elphaba had that same journey, trying to fit, and it doesn’t work. Your only choice is to be who you are.”

To colour in those bold outlines a little: Erivo was born in south London in 1987, to Nigerian parents who had fled the long and chaotic aftermath of the Biafran war. They split up when Erivo and her sister, Stephanie, were tiny, and she is estranged from her father. He disowned both his daughters at a tube station when Erivo was 16.

Her mother, a nurse, raised them on her own, and knew Erivo would be a singer from when she was 18 months old, the legend has it, though Erivo dates it from when she was five. “You don’t really know the difference when you’re five. I knew that whatever I was doing seemed to make people happy, but you’re just making noise. I properly realised I could sing when I was about 11.” This was at an all-girls Catholic school in Clapham called La Retraite, which had an amazing music department. She took up the clarinet, the saxophone, the viola, then dropped the wind instruments. “When you’ve got an instrument in your mouth, you can’t sing. I can pretty much sing everything, but that comes from curiosity, starting with Magic FM – Mike and the Mechanics, Aretha Franklin, Kate Bush: all of that music was part of the vocabulary I used to learn to sing.”

That off-the-radio Aretha apprenticeship became, in 2021, her performance in Genius: Aretha, a National Geographic series for which she was nominated for a Primetime Emmy, outstanding lead actress. Her first big screen break was in Steve McQueen’s Widows, in 2018.

“My family’s not a musical, acting family. I had no clue how to do this,” Erivo says, and there is plenty of pluck and luck in her route from being a kid with a gigantic voice, getting to drama school, into fringe musicals, into the West End and then Broadway, but there are also a lot of obstacles that read like snobbery and racism.

She started a music psychology degree at the University of East London. “I just went for anything that would allow me to have anything to do with music and singing.” It was boring – she puts that more tactfully: “I wasn’t stimulated” – and she dropped out and went to work at Theatre Royal Stratford East, in the bar, as an usher, “I just thought: ‘If I’m in a theatre, maybe there’s a chance, I could meet a director, I might just meet somebody.’ You don’t realise until you’re working in a theatre that there’s a weird division – an invisible line comes up. You think you’re in this hub but you aren’t.”

She says she was baffled when she was refused point blank the chance to audition, thinking: “But I’m right here. What’s the worst that could happen? I could be terrible, I could be great, you don’t know. I could just try? You could say no, and I could go back to work.”

She caught a break when artistic director Rae Macken, who had cast her as the lead when she was 15, in a Young Vic youth outreach production of Romeo and Juliet, came to run a short course at Stratford. “She said: ‘I think you should train.’ I don’t know what she means. She said: ‘I think you should go to Rada.’ You know, I didn’t know drama school existed until today, and she wants me to go somewhere beginning with ‘Royal Academy’.”

This would have been 2007, and drama schools generally, particularly the elite ones, were still famously tough on everyone. It was part of the training, partly some actorly thing about dismantling the ego, and partly a preparation for the outside world of performing, where rejection is the norm and can be encountered for something as trivial as your hair or as existential as your soul.

That was the theory, anyway, but in 2020, when the Black Lives Matter movement hit British institutions and they started to profess their support, Rada (among many others) was hit with waves of accusations of hypocrisy, from former students denouncing the treatment they received and the blank lack of inclusivity. When Erivo and David Harewood became vice-president and president respectively in 2024, they were the first actors of colour in the school’s 120-year history to take those roles.

In 2020, Rada apologised and said that it “has been and currently is institutionally racist”. Erivo doesn’t describe her experience there in those terms, but hearing her talk about it, the only way you’d call it “not racist” is if you said: “Not just racist, also classist.”

Just before she started at Rada, she had auditioned for and won a backing-singer gig for Westlife, which would have paid 10 grand, “and that would have done it. That would have paid off everything.” But it would have meant she missed the first two weeks of the course, “and the people running the place don’t necessarily understand people who aren’t given everything. They don’t understand what that experience looks like.” So they said no. (“There was another student in a play, missing two weeks, and that was fine; it was just a weird looking down on a backing-vocals gig.”)

She had to work for the shirtmaker Thomas Pink all the way through the course. “I genuinely had to work much harder than other students, and I got penalised for it. I’d come in exhausted, and they’d say: ‘Well, she’s not dedicated. She’s not concentrating.’ It took me a long time to make people understand that I wasn’t lazy – I was just tired.” The knock-on effect was that in student productions, which is where you’d pick up an agent, she was always given tiny parts. “First, it was because they thought I wasn’t concentrating. It was like a punishment. The second time, I can’t even remember the excuse. The third year, the excuse was, they thought I was ‘efficient’ and other people needed more help.”

She ended up putting on her own cabaret and landed an agent from that. “I’ve never really talked about this before. I’ve never really talked about how tough my journey has been. I think I’m just so grateful, and you take the good with the bad. Learning what I needed to learn at Rada meant that I could learn what I needed to learn in theatre, and learning what I learned in theatre meant I knew what to do on Broadway, and that’s set me up for TV and film.”

She got some formative training at Rada. “My acting teacher, [the late, renowned] Dee Cannon, she really understood what I was, and understood that there were preconceived notions of what black women should be, the strong black stereotype. And she said: ‘That actually is not where you excel. Where you excel is softness, and vulnerability.’”

The only break she got in the British TV industry was from Michaela Coel, very early on, in Chewing Gum, and they remain close. But musical theatre roles landed fast, each one bigger – bigger part, bigger stage, bigger splash – than the last. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg at the Gielgud, then Sister Act, during the tour for which “I found out that The Color Purple was auditioning. I knew in my gut I was supposed to do that show. I sounded like a crazy person. People would ask about other roles, and I’d say: ‘No, I’m meant to be Celie.’ They wouldn’t see me – I don’t know why.” Fate (in the form of the actor Jason Pennycooke) intervened on her behalf and she got that part, which was fringe in London (the Menier Chocolate Factory), but transferred to Broadway two years later, where audiences would break into a standing ovation after Celie’s self-actualisation banger I’m Here.

If from a distance it sounds as if Wicked was an out-of-the-blue, lottery-level lucky strike, from stage to huge screen, that’s probably just by comparison with Grande, who has been megafamous for years. Erivo had had a number of major film parts, part of an A-list ensemble cast in Bad Times at the El Royale in 2018, and playing Harriet Tubman in Harriet the following year. It is still hard to overstate the gear change, though: Wicked the film, and Wicked the gif creator, the phrasemaker, the comical fairytale of Erivo and Grande’s friendship, are all so massive.

The two women basically start crying with mutual adoration whenever they are interviewed, but most famously when a journalist started a question with: “People are taking the lyrics of Defying Gravity and really holding space with that and feeling power in that.” Now that’s all the internet can talk about, “holding space”, and seriously, did Erivo and Grande fall in love during this movie? They do have one more joint tattoo after all; where and what of is a secret. Erivo bats all that off, diverting back to her relationship with her character Elphaba, and how: “You can’t help but take some of that alienation on. Especially when you know how it feels. I think about the dining hall scene, where everybody’s looking with so much hostility. When you play those experiences, you take it in. My way was always to block everyone out.”

Overall, the adjudication of the internet, TikTok at least, is that Erivo and Grande are just really good friends. Besides, Erivo’s in a relationship with the screenwriter Lena Waithe, who described the first time she saw Erivo, at the Met Gala in 2018. “I remember [thinking], ‘Who is this tiny person with a British accent?’ We’ve just been vibing ever since.”

Five minutes from the end of the interview, my 15-year-old came in. She was meant to ask a question about Wicked II, but she just said: “You’re so amazing” a number of times, and Erivo was incredibly, step-out-of-professionalism warm and chatty, about the fact that my daughter’s secondary school is around the corner, historically rivalrous, from La Retraite. So I asked about Wicked II, and it “might cause a ruckus,” she said. “It’s a darker movie. They’ve grown. They’re not in school any more. I think it’s really juicy.”

She has three other film roles confirmed, but not public yet, another one waiting for a decision, and she is releasing an album of her own songs this year, with maybe a mini-tour. “I’m an oddball, so I’m going to try and find ways to make it make sense to me.”

I think gen Z are on to something: I think she is amazing, and there’s a lot to hold space for, once you’ve figured out what it means.

Wicked is in cinemas and available to rent or buy at home

3 months ago

54

3 months ago

54