‘You can’t get this wrong, they grow by themselves!’ she laughs.

I love a lush garden and dream of being surrounded by the cacophony of flowers, bees and butterflies that were a staple of my Indian childhood. But I am reconciled that the decidedly meditative act of sowing, tending and reaping must wait until retirement.

My patient has other ideas. At the end of a consultation, when I ask how she is coping, she furnishes images of her indoor garden. Shrubs, palm fronds and dainty blooms. But one plant captures my whole attention. It stands tall, nearly touching the ceiling as if pulled there by an invisible string.

Its leaves are big and bright, sturdy in the way of broad shoulders. They grow all the way along the stem. No broken or curled leaves, no hesitant shoots, just a solid staircase of soothing green all the way up. So, when she says that this is the thing she looks to for tranquillity, I understand. This plant has a presence. And a certain dignity. I can imagine holding a quiet dialogue with it.

Noting my interest, she does what thoughtful people do. The next time, she presents me with a baby version of the plant.

I am touched, but find myself confessing that even supposedly ‘low maintenance’ plants perish under my watch. You’ll be fine, she laughs. The subtext is, ‘even you can do this’.

I place the white pot inside our front entrance where I can see it and remember her. The plant has two nascent leaves. It looks content in the corner it shares with the fake orchid.

Owing to a family history, my patient has an aggressive cancer. Her measured temperament does no justice to her bad luck. But a pragmatic acceptance of her situation mixed with resolute determination to do her best is inspiring. In her case, the best turns out to be a complete response to treatment.

Every oncologist has an indelible memory of a patient’s disease unexpectedly melting away. Later, there will be nuanced questions about the how and why, but in that moment of discovery, there is only happiness – and a tsunami of hope.

When her disease eventually returns, her failing body serves only to gird her spirit. As I rue my inability to make a tangible difference to her survival, she repeatedly tells me that she is not afraid to die. Searching her face, I see that she is serious and am moved by her equanimity. Her funeral overflows with well-wishers, testament to a short life lived with great love and unceasing generosity.

Months later, during an intense Australian summer, I notice one leaf of the plant go brown and another curl inward. The other four leaves look healthy. I take extra care to water the plant, hoping this will do the trick. Next, I sprinkle some plant food, willing its revival. I move it from sun to shade and shade to sun. But nothing I do is good enough. I am not usually sentimental about plants, but this exercise tests me.

For weeks, I wonder why I am taking extraordinary measures until I realise that the plant’s journey is a metaphor for my patient’s life.

At the start, she was youthful and energetic, and my early care kept her that way.

Then, as her health took a downturn, my efforts stopped helping.

More chemotherapy was not better; more surgery was not the answer; until finally, even more worrying was pointless. In hospice, under the fog of sedation, she smiled at me with her eyes, said thank you and went back to sleep. The once consoled was now doing the consoling.

‘Indoor plant dying: why?’ I ask Google.

Underwatered, overwatered, overfertilized, under fertilized, too much sun, not enough sun. And if it’s none of those, Google unhelpfully declares, then the diagnosis is: failure to thrive.

Is it a coincidence that this was the opaque diagnosis I had offered my patient when she asked why, despite everything I was doing, she never felt quite right? I feel glum, and to an extent, thwarted by nature. Again.

I wonder if my patient’s more deliberate care and attention might have resuscitated the plant. Did hers grow into an indoor tree because it was serving a greater purpose while mine just stood guard at the front door?

‘Do you want me to replace it, love?’ my gardener offers innocently. With my track record, we have had this conversation before, and I have usually, gratefully, agreed.

‘No need’, I swallow, feigning a nonchalance I don’t feel. What good would it do to burden him with why?

Abandonment is just a word, but in the doctor-patient relationship, it has enormous implications. Many cancer patients report that once they stop responding to treatment, their oncologists grow uninterested. From my vantage point, this is neither fully true nor so simple – but that doesn’t really matter.

In this age of modern medical miracles, all I could offer my patient was that I would walk with her until the end. I was there the night before she died, still processing my disbelief and devastation.

As we enter the cooler months, I am hoping anew. Maybe the plant will shake off its ailment and reach for the ceiling. Or maybe that’s an unlikely story I am telling myself.

Like their patients, doctors cling to hope, too.

-

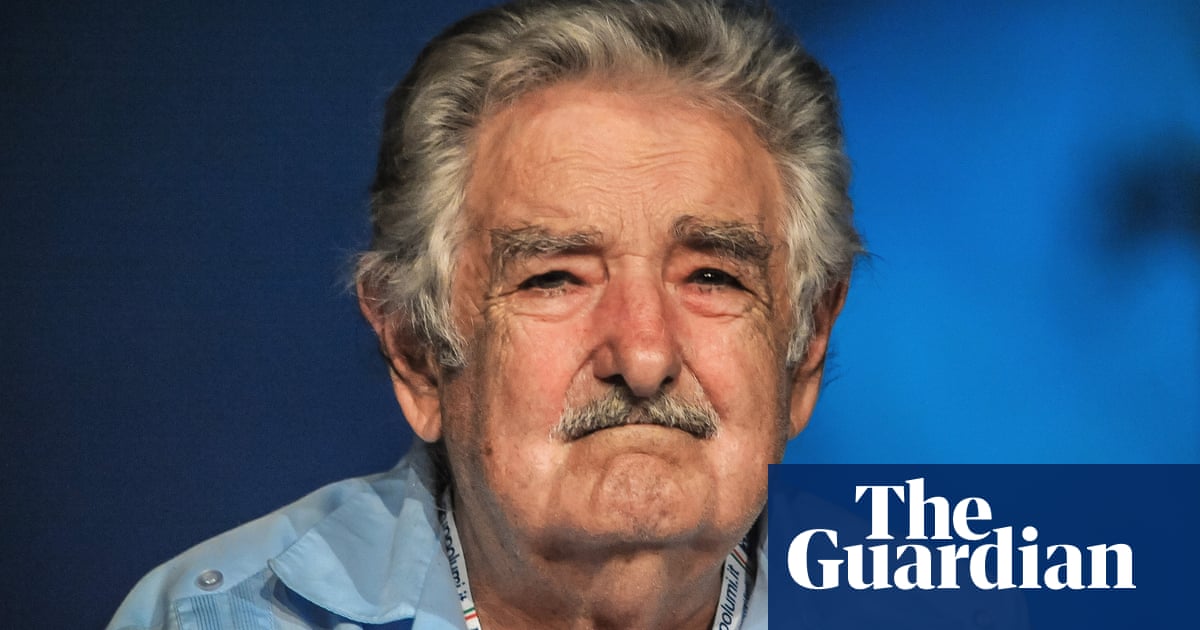

Ranjana Srivastava is an Australian oncologist, award-winning author and Fulbright scholar. Her latest book is called A Better Death

1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31