One sunny March day on Angel Island, a hilly landmass in the middle of the San Francisco Bay, a dancer with a 40-ft braid attached to her head glided across a narrow concrete walkway. The audience sat on chairs in front of a long wooden building: a former detention center where – from 1910 to 1940 – half a million people, the majority Chinese, were held for months, even years, in prison-like conditions.

Sometimes called “the Ellis Island of the west”, Angel Island’s immigration station is the unlikely setting, and inspiration, for an ambitious new work by the Oakland Ballet Company. It’s based on the people from 80 countries who were confined to the the island’s detention center, which was the result of the Chinese Exclusion Act and other racist laws designed to keep Asian people out of the United States. In response, the detainees carved over 200 poems onto the walls expressing their anguish and rage.

As the ballerina moved, her braid stretched behind like the train of a gown while four other dancers shifted around her. One carried a wooden boat symbolizing the immigrant’s journey from China to America. As the dance progressed, the braid seemed to change meaning. At one point, it was like a line of ancestry or memory connecting the woman to her home country. The next, it became a rope lashing the dancers together. When the woman tried to flee, it pulled taut, holding her in place. Then she wove it like a skein of yarn and cradled it in her arms. By the end, the braid was snarled around her body as she crumpled to the stage.

The Angel Island Project premiers on 4 May at Oakland’s Paramount Theatre, with more performances planned in the fall. The ballet is the work of seven Asian American and Pacific Islander choreographers, each interpreting a poem from Angel Island and other harrowing tales in Chinese American history. It’s set to an oratorio by Chinese-born composer Huang Ruo, which will be performed by the Del Sol Quartet. Throughout, a choir will sing the words of the poems in Mandarin and English. “Like a stray dog forced into confinement, like a pig trapped in a bamboo cage, our spirits are lost in this wintry prison,” begins one of the verses. “We are worse than horses and cattle. Our tears shed on an icy day.”

This poignant piece of theater has origins in the Covid pandemic. In 2021, Graham Lustig, Oakland Ballet’s artistic director, was dismayed to learn that one of his dancers was subjected to racial slurs due to the rise of anti-Asian hate in the US. In response, he partnered with the Oakland Asian Cultural Center and launched the annual Dancing Moons Festival, becoming the first program to feature the work of all-Asian artists.

In 2023, Lustig discovered Ruo’s oratorio Angel Island, which was composed in 2021, and began developing a ballet about the detainment center.

The project is expansive, an eight-part ballet exploring different facets of Pacific migration with 12 dancers, seven choreographers, a string quartet and 16-piece choir. “It’s the biggest project the company has ever taken on,” says Lustig. “And at its root, I think it’s a very compelling story about American history, which is less well-known. I think it deserves to be shone a light on.”

This message has taken on even greater significance in recent months, as Donald Trump’s administration has begun its aggressive campaign to arrest and detain immigrant residents in the US, raising alarming parallels with the dark history of Angel Island a century ago.

Phil Chan, an author and choreographer who lives in New York but grew up in Berkeley, created two pieces for the ballet. Like many Bay Area residents, he went to Angel Island on field trips as a child, but the history didn’t sink in at the time. It wasn’t until this project that he absorbed the full meaning of the poems on the barrack walls.

“It has been really special to dive into this history, especially right now, and to ask some of those questions about who belongs here, who was allowed to be here, who wasn’t,” he says. “But at the end of the day, we’re all Americans, right? I don’t see it as just a Chinese American story. This is really an American story. It’s part of how we, all of us, got here.”

Resurrecting history

While European newcomers stayed only a few hours at Ellis Island, other immigrants on Angel Island were typically detained from two weeks to six months. The longest stay was almost two years. They were interrogated, separated by gender, exposed to poor living conditions, and forced to endure invasive medical exams. It was all part of Chinese exclusion, a series of restrictive immigration laws that started with the Page Act of 1875 and continued until China became a US ally in the second world war.

The different choreographers provide varied viewpoints within a larger story about the immigrant experience. In the case of Seascape, the piece with the braid and boat, classical Chinese dancer Feng Ye was given the poem: “The sea-scape resembles lichen twisting and turning for a thousand li. There is no shore to land and it is difficult to walk, With a gentle breeze I arrived at the city thinking all would be so at ease. How was one to know he was to live in a wooden building?”

Ye explains she chose the braid because of its importance in Chinese culture, the belief that hair carries memories through time, and her personal associations of homesickness when she first moved to the US from China nine years ago. Working with a 40-ft prop presented technical hurdles for the performers, who risked tripping over or getting tangled in the braid. But, she adds, she embraced the risks as part of the dance.

“It was a very big challenge because there are a lot of uncertainties, things we cannot control,” Ye says. “But it’s an interesting part of it to me. That’s like history. We don’t know the next step. We never know. And you cannot control it.”

Waves of migration

In addition to the immigration crackdown, the federal government is also censoring artistic expression it deems DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) in an attempt to silence voices that don’t fit in with the administration’s narrative of America. It has eliminated arts funding for underserved communities and is rescinding grants previously awarded for creative and educational endeavors. In early April, the government terminated a $25,000 grant to the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, which preserves and elevates the history of migration to the US through the Pacific. Executive director Edward Tepporn expects a second grant will soon be revoked, resulting in a loss of $100,000.

“Without this funding, it definitely hampers our opportunities and abilities to tell these often invisible stories,” Tepporn told CBS News.

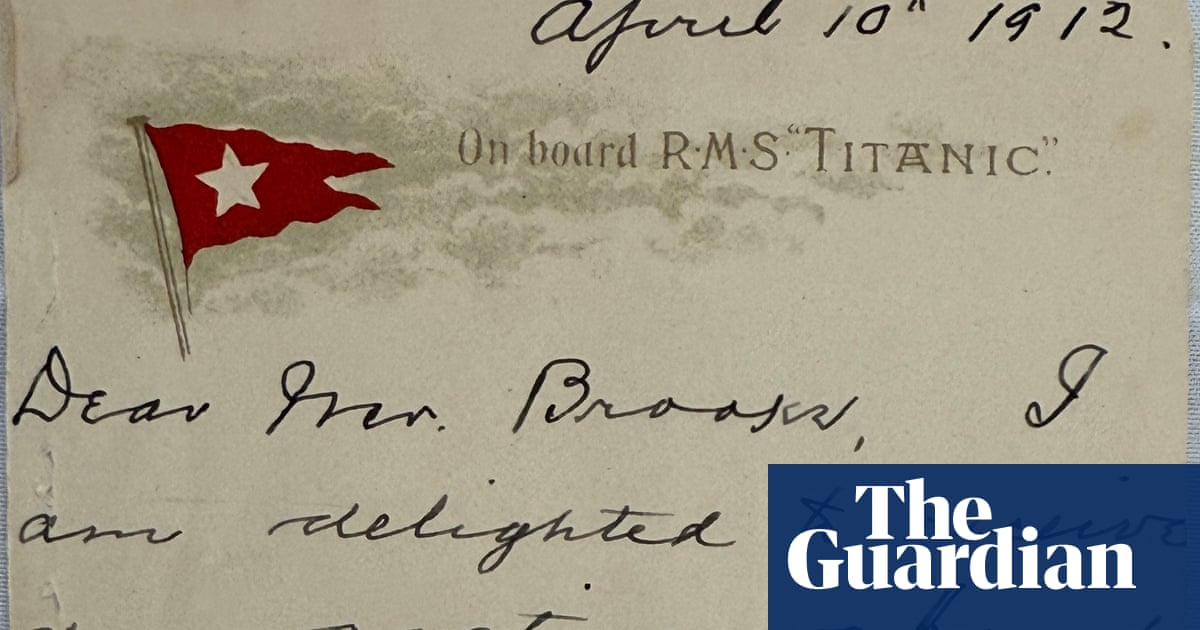

Given this, a ballet centering the talent of Asian and Asian American artists and depicting the painful consequences of history feels especially relevant. For example, a segment in the ballet entitled The Last Chinaman From the Titanic portrays the six Chinese men who survived the sinking of the ocean liner in 1912. One individual, Fang Lang, was found clutching a floating door, likely the inspiration for the well-known movie scene starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. However, when the survivors reached Ellis Island, they were barred from entering the United States and denied medical care. Chang Chip developed pneumonia and died in 1914.

In the suite, ballerina Jazmine Quezada is hoisted into the air by the other dancers. As they turn, pushing her as high as they can, she lifts her arm skyward, reaching for something that she doesn’t receive. There is nothing to do but drop her empty hand.

Chan’s finale for Angel Island Project focuses on waves: the dancers imitate the ocean waves bringing immigrants to this country, which turn into waves of people who come and keep coming, throughout the generations, despite exclusionary laws. There’s resiliency and hope in the act of migration, even as other things are left behind.

It’s a message that rang true for many of the dancers, a mixed group from different backgrounds who brought their individual histories to the ballet. After the March preview on Angel Island, a woman asked the dancers if they had personal connection to the material. As the bay sloshed in the background, Quezada raised her hand.

“My dad is from Mexico and my mom’s family is from Mexico, and they immigrated here. It’s just bringing up feelings about how much they struggled to get here and create a better life,” she said, tearing up. “I love them so much and I miss my grandparents. And I’m so glad for what they have done for me.”

7 hours ago

6

7 hours ago

6