Euan Uglow, they say, is an artist’s artist, and therein lies the problem. If you were approaching his painstaking canvases out of curiosity – how to construct the figure, capture precise perspective, proportions – I can see how their visible workings (complex little dashes and crosses and plumb lines and geometric grids) would prove revelatory. But lots of us come to art to be inspired, transported, to feel. And for all their technical prowess, Uglow’s 70-odd regimented paintings at MK Gallery leave me cold.

First, some context, which we get immediately upon entering – in a slightly maddening move, the five-room retrospective of the artist opens with a room of seven paintings, of which only two are by him. After studying at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in London from 1948 to 1950, he moved to the Slade. He was influenced by Paul Cézanne and Alberto Giacometti, as well as three tutors, all of whom are represented here.

Things pick up in the following room, which brings Uglow, who died in 2000 aged 68, into better focus. In 1959 he rented a studio in Battersea, London, and began to develop his own style – painstakingly devised paintings based on intense observation. In the early works are flickers of life. There, in the beautifully plump and juicy beads strung around the slender neck of his friend, Gloria Ceccone, and the bright flashes of cerulean and ochre bursting against black in the striking portrait of the Ghanaian painter and activist, Marigold.

I’m warming to him until I come face to face with the first of a series of large-scale nudes, this one spliced and diced in a way that makes me think of a meat cleaver. Which is bizarre, really, because there’s nothing meaty about Uglow’s naked women, a world apart from his more popular London contemporaries Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud. If anything, you could compare them to carcasses, any fleshiness picked off the bones, which jut out at awkward angles. The central room is devoted to nudes reclining on one wall and standing on the other, a frieze of female form. Frieze, or freeze: the word that springs to mind is static. The left breast of the woman in Root Five Nude (1974-75) is upright and stiff, when surely it should be flopped over.

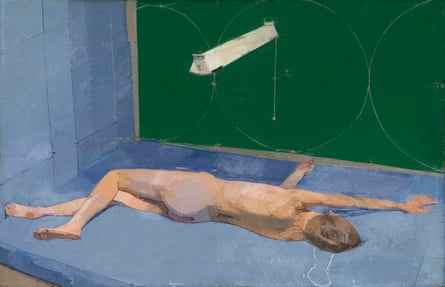

Like Freud, Uglow made huge demands on his models, scrutinising them for days, weeks, months, years. He used three models for Three in One (1967-68) – a ghostly white outline hints at the arm of a previous girl, while the clunky white heater hovering above underscores the artist’s chillingly laboured process. Just look at the dates: The Diagonal (1971-77), an extraordinarily elegant and at the same time excruciating image of a long, lean model stretched plank-like on a folding chair across a horizontal canvas, took six years. It wasn’t uncommon for his sitters to bow out partway through a picture.

Which is what happened with Cherie Blair, who appears twice, the second time semi-naked in an open blue shift dress (the tabloids had a field day when the portrait came to light). A trainee barrister, she was introduced to Uglow by her head of chambers, and posed for him before realising she didn’t have the time that Uglow demanded of her. Hanging beside her unfinished portrait is a more polished canvas modelled by a substitute.

There are moments of brilliance. The pinkish sole of the right foot in Pepe’s Painting (1984-85) is intimate and tender, and there’s masses of character in the adamantly flexed left foot of that model in The Diagonal. But the pink legs of the striding model in Zagi (1981-82), seemingly on the brink of movement, look as if they’ve just emerged from a too-hot bath. And Nuria (1998-2000) is a Sarah Lucas bunny without the humour.

Which is the trouble with Uglow. He takes himself so very seriously. He once said: “I want the brain to intervene between the observation and the mark.” Another often-quoted line: “The proper subject of a painting is painting itself. It’s not what gets painted that matters, it’s how.”

That may be what mattered to the artist, but it doesn’t always make for an enriching viewing experience. It’s true that, in the age of AI, there is something reassuring, even rousing, about seeing the time and effort he put into his pictures – but too much methodology sucks the life out of art.

The exhibition ends with a series of still lifes: a quite lovely daisy; a lonely plastic cake, which does nothing for me after seeing Wayne Thiebaud’s creamy and moreish slices at the Courtauld last year; a toy palm tree (your guess is as good as mine); a slumped and spoiled peach.

For a brief moment, I wonder if I’m witnessing a glimmer of self-parody when I read the title of the final work on show: Mouse Loaf (1991-92). Uglow worked on the painting for more than a year, insisting on his uncompromisingly fastidious approach even as the mound of bread was gradually nibbled by rodents. To prevent it from collapsing, the artist filled it with plaster. Life chewed cold.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1