Joan Didion, the original girlboss of American letters, keeps inspiring new takedowns. Critiquing Didion’s racism, the writer Myriam Gurba compared her to an onion: “She’s very white, very crisp, and she makes people cry.” An anonymous woman in a Los Angeles bar called Didion “that lady from Sacramento”. (Didion might have fooled the New York Times, but Angelenos know she wasn’t from Los Angeles.)

Eve Babitz’s recent takedown of Didion might be the most extraordinary, though, because it has been issued from beyond the grave.

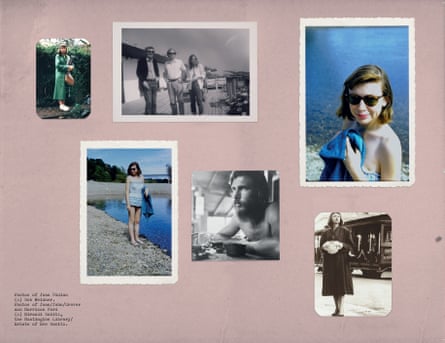

Babitz, who died in 2021, was a Hollywood it girl of the 60s and 70s, and the author of several witty, freewheeling chronicles of her LA life, including Eve’s Hollywood, and Slow Days, Fast Company. As famously “boobalicious” as Didion was famously thin, Babitz was at the center of the wild 60s LA scene that Didion captured in her 1979 book The White Album. She dated multiple men who championed Didion’s work, while Didion helped Babitz publish her first Rolling Stone article and edit her first book. Didion profiled Jim Morrison, calling him one of the “missionaries of apocalyptic sex”. Babitz actually had sex with him.

The women’s relationship was a fraught one, and when Babitz died, she left behind boxes full of unsent letters, including one to Didion – a letter that is simultaneously furious and enamored, attacking how Didion performed her role as an acclaimed female journalist, and the dynamics of her marriage to John Gregory Dunne, a less successful writer.

“Could you write what you do if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” Babitz asked in the unsent 1972 letter. “Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening? Would the balance of power between you and John have collapsed long ago if it weren’t that he regards you a lot of the time as a child so it’s all right that you are famous. And you yourself keep making it more all right because you are always referring to your size.”

Didion, who had recently published a takedown of the women’s movement, had told Babitz that she did not like Virginia Woolf’s diaries. “It’s entirely about you that you can’t stand her diaries. It goes with Sacramento,” Babitz wrote. “You prefer to be with the boys snickering at the silly women and writing accurate prose.”

Lili Anolik, the journalist and Babitz biographer who discovered the unsent letter, has turned it into the heart of a new dual biography, Didion and Babitz. The book is a meditation on what it takes for a woman to become a famous writer – and an examination of just how ugly and messy a literary career like Didion’s, or a party girl life like Babitz’s, can look behind the scenes.

It’s also a takedown of Didion, portraying her as calculating and brutally careerist, and examining just how much of Didion’s fame as a chronicler of 60s counter-culture relied on her upper-middle-class social position, and the series of well-connected men who championed and protected her.

Anolik interviews the right-leaning political journalist Noel Parmentel, Didion’s charismatic lover in New York, who helped get Didion’s first novel published but would not marry her. Parmentel describes essentially arranging the famous literary marriage between her and Dunne, who was, he said, “not brilliant, but bright”, and, unlike him, willing to “be at the breakfast table every morning” and “edit her line by line”.

Anolik was drawn to the contrast between Didion, the “controlled, eyes-on-the-prize” former sorority girl, and Babitz, a “walk-on-the-wild-side type” who was “emotionally sloppy but morally courageous”, as she told me in a recent interview.

“What I like about Joan is how extremely she wanted to be a great writer, more than she wanted anything else,” Anolik said. “If I expose anything, or reveal anything, it’s to understand the price she paid to be Joan Didion.”

Babitz was much less strategic in how she operated. “She made everything impossible for herself. She made it so hard,” Anolik said. Often, Babitz did things that made Anolik think: “Eve, that’s so fucking stupid – dont’ call yourself a groupie” and give people “ammunition to dismiss you”. (Didion’s husband called Babitz “the dowager groupie.”)

When Babitz’s books were originally published in the 70s, they didn’t get much attention. By the early 80s, when Didion had cemented her fame with The White Album, Babitz was dealing with a cocaine addiction, and eventually had to move back in with her mother. In her later decades, she struggled with Huntington’s disease and a terrible accident that left most of her body covered with painful burns.

Anolik is unapologetically on Babitz’s side, the champion of a once-forgotten writer she helped restore to the canon with a 2014 Vanity Fair profile, portraying Babitz as an “irresistible hybrid of boho intellectual and LA party girl”.

Though she lived in LA for 24 years, Didion took the stereotypical serious person’s view of the city, as “a spiritually starved place full of glamorous and empty people”, Anolik told me. But Babitz, who thought she would never be treated as “a major important serious author”, refused to do that: “I’m a gossip storyteller who likes LA rather than hates it,” Babitz wrote in one of her letters. Unlike Didion, Babitz was actually from Los Angeles, and had gone to Hollywood high school, the inspiration for her first book.

After Anolik’s profile, Babitz’s literary career belatedly took off. Her books were reissued by NYRB Classics, with introductions from a series of young journalists who claimed Babitz as one of their own, falling in love with her blunt, confident, over-sharing prose, which can feel much more current than Didion’s postured mid-century malaise.

When I moved to Los Angeles at the height of the pandemic, Babitz was one of the first LA writers people urged me to pick up. Reading Eve’s Hollywood during those months of isolation made me feel like I was cruising through the streets with a brilliant, fast-talking, gloriously petty local. More than one California art girl I know has decorated her bathroom with the iconic Julian Wasser photograph of a nude Babitz, at age 20, playing chess with Marcel Duchamp. (Anolik notes that Didion engineered the photograph as revenge against her lover at the time, an art curator who did not invite her to an important opening.)

Neither Didion nor Babitz’s books offer much today in terms of revealing political analysis, though Didion, who was always something of a political reactionary, is certainly a better writer than the journalists satirizing woke-ism today.

Other famous local authors – like the leftist historian Mike Davis or the speculative fiction writer Octavia Butler – understood California more deeply, and produced books that still feel “eerily accurate”, even “prophetic” of the conflicts Los Angeles is facing now.

But Didion and Babitz’s stylish self-mythologizing remains relevant, the precursor to the social media streams of gen Z women invoking not a full “mental breakdown”, but a diminutive “menty b”.

Some of the details about the two writers’ fast times in LA are delightfully absurd: before he made it in the movies, Harrison Ford was a pot dealer, and then Didion’s carpenter at her house in Malibu. Ford was, reportedly, not a very diligent craftsman, but according to Babitz, who knew: “The thing about Harrison was Harrison could fuck.”

Others are sadder, like Babitz’s constant anxiety about her weight, including her belief that Mick Jagger did not like her because he thought she was fat, and Didion’s intense, meticulously controlled thinness. Despite cooking elaborate meals for other people and touting her culinary skills, Didion “allowed herself no flesh”, Anolik writes.

Didion and Babitz died six days apart in December 2021: “I want to believe that Joan Didion lived an extra week out of spite so she could officially outlive Eve Babitz,” one journalist wrote in a viral tweet at the time.

Critics have had mixed responses to Didion and Babitz. Not all readers will be compelled by a 1960s story about two white women fighting for literary recognition while Watts burns somewhere in the background. Several reviewers have said they were particularly unconvinced by Anolik’s argument that the two writers represent the “two halves of American womanhood”.

But the Hollywood buzz around the book has been undeniable. The actor Emma Roberts chose Didion and Babitz for her book club, and she hosted a launch party for the book early this month at Chateau Marmont, the setting of so many of Eve’s stories. There were bouquets of cigarettes and lighters printed with Didion and Babitz’s names. Celebrities from Oscar-winner Da’Vine Joy Randolph to Elizabeth Olsen to Nicole Richie took turns reading some of Babitz’s letters aloud.

It was a very particular kind of seance. Three years after her death, Babitz’s one-liners were once again echoing through the old Hollywood hotel, now in the voices of a series of young actresses. Didion might have won most of the laurels. But it’s possible that, on their friendship, Babitz was getting the last word.

3 months ago

43

3 months ago

43