It may have been a quiet January transfer window, but even so, thousands of new shirts will be printed for Lucas Paquetá, returning to his former Brazilian club Flamengo, while his West Ham shirt instantly feels old. Not to mention the thousands of other players moving from one club to another. Uefa estimates that up to 60% of kits worn by players are destroyed at the end of the season, and at any one time there are thought to be more than 1bn football shirts in circulation, many of which are discarded by fans once players leave.

The good news is that lots of designers are bringing their upcycling skills to old kits, taking shirts and shirring them, sewing them or, as in the case of designer and creative director Hattie Crowther, completely transforming them into one-of-a-kind headpieces. “I’m not here to add more products into the mix, I’m here to reframe what’s already in circulation and give it meaning, context, and longevity while staying culturally relevant,” says Crowther, whose creations involving the colours and emblems of Arsenal, Liverpool and Paris Saint-Germain, are, she says, “a response to how disposable football product has become”.

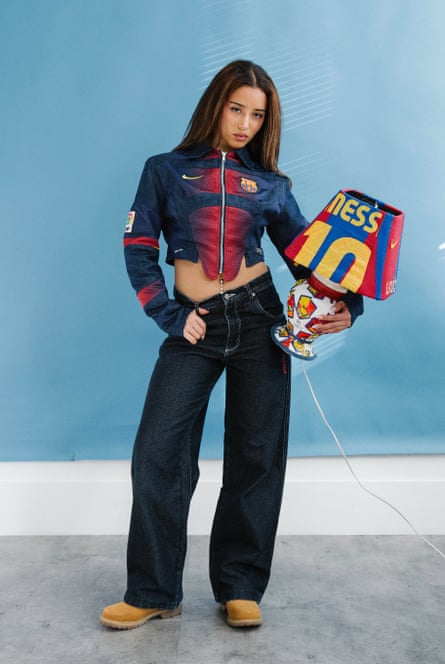

Crowther’s project, Soft Armour, is just one example of how women are leading this reinvention and rethinking of football shirts. Designers Renata Brenha and Christelle Kocher along with brands (re)boot and Rose Ojo have all reworked football shirts to create everything from dresses to puffer jackets. The clothing store Vintage Threads has a rework service transforming old football shirts into new, custom pieces, ranging from a shirred top (£180) to a leather football jacket (£525).

Many of its customers are women who, according to the head of the rework project, Caitlin Finan, want something “that’s maybe more their style than a big, baggy football shirt that doesn’t fit them well. That’s why we had a lot of interest in shirred football tops last summer. It just makes it a little bit cuter.”

Vintage Threads founder, Freddie Rose, suggests that the uniqueness of the pieces, compared with the templated football shirts we’re used to seeing, is what attracts people. The difference in the price-point might be hefty but, as Finan points out, unlike in the case of fast fashion football shirts, “the person [who made the reworked garments] got paid correctly”. Plus, “it’s definitely a more valuable way of expressing your personal style than a shirt,” she says.

Football and fashion journalist Felicia Pennant goes one step further and argues that “reworked football shirts are the answer when tackling the environmental waste that occurs when so many football shirts are being released every season”.

Most modern football shirts [professional and fan shirts] are made from virgin polyester, a type of plastic created from oil. The synthetic material’s properties are great for performance (it’s light and doesn’t retain moisture); fantastic for style (bold colours and designs can easily be applied to the fabric through sublimation printing); and perfect for profits (it’s cheap, costing half as much per kilo as cotton).

But it’s extremely energy-intensive to extract and the resulting polyester garment releases microplastics with every wash, before taking up to 200 years to break down – still quicker than it will take Spurs to win the league. Worse still, the shirts are more overproduced than ever with clubs like Bayern Munich going from releasing three kits every four years in the early 1990s to about 20 kits over the same period 30 years later. No wonder an estimated 100,000 tonnes of sports kit from the retail market ends up in landfill every year in the UK alone – that’s 951 football shirts per minute.

Of course, not all clubs release kits in such excess. My football shirt, Walthamstow FC’s William Morris-inspired away kit, ran for two seasons. The celebration of heritage via a local hero and the use of Morris & Co’s kaleidoscopic Yare design, made it more than a football shirt. It was a symbol of pride and a fashion statement that I wore gleefully around my home town.

The increasing popularity of retro football kits has also helped to ease the flow of garments to landfill sites. Kim Kardashian and Timothée Chalamet have been spotted wearing an oversized Roma 1997/98 shirt and the 1994 Mexico home kit respectively, while on the fashion marketplace Depop, searches for them were up 38% over the last six months.

Gary Bierton, co-founder of the retailer Classic Football Shirts, believes that “preloved football shirts remain loved because every shirt has a story, and that enduring legacy helps keep the product relevant”. But it’s not always the club’s narrative that makes a shirt appeal: he recalls once complimenting an LA local on a Sheffield Wednesday shirt, to which they replied: “What is a Sheffield Wednesday?” They had been drawn to the colours and stripes.

Whatever the reason, keeping shirts in circulation is a good thing. Not-for-profit campaign Green Football estimates that extending the life of a shirt by nine months can cut its carbon, water and waste footprint by up to 30%. Its 2025 campaign, Green Football’s Great Save, focused on saving kits from landfill by encouraging people to swap, donate and repurpose their kits.

Nottingham Forest Community Trust ran a workshop for local schoolchildren to turn football shirts into tifos, those huge, fan-organised flags that can take over whole sections of stadium crowds. By embedding climate consciousness in traditional football arenas, Green Football was able to meet fans where they were at.

But how much of a difference will these examples make in a wider consumerist culture hellbent on overproduction and overconsumption? Football’s hyper profit-driven nature is often in conflict with sustainability. Take for instance the fact that competing stakeholders enable a club like Manchester City to wear football kits made 95% from recycled polyester from textile waste while their front-of-shirt sponsor Etihad Airways emitted an estimated 1.9m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2023.

Joanna Czutkowna, the director of 5Thread, a consultancy specialising in sport, apparel and sustainability, believes reactive measures such as upcycling and vintage football shirt collecting are great entry points into discussions about sustainability. But even more change could come by integrating a circular economy into football’s ecosystem. “Circularity is about keeping products in use for as long as possible, getting maximum value,” she says.

That value, she points out, can be financial as well as environmental. “Why sell your shirt once when you can sell it five or six times [through the pre-loved football shirt market]? Why doesn’t every club have an in-house upcycler they support rather than one-off projects?” There is, she says, “money being left on the table and I think that’s something clubs might be missing.” According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, circular business models could be worth $700bn for the global fashion market by 2030.

Some clubs are already starting to see the long-term benefits of a circular business model. In 2024 and 2025, Brighton teamed up with sustainable upcycling brand, FC88, to create bum bags and bucket hats from misprinted youth football shirts. Nicole Bekkers, founder and CEO, says football clubs are more open to upcycling than in the past. “Once clubs see the financial and fan engagement upside, it triggers broader conversations about production volumes, circular design, resale, and material choices for future kits.” But, she says, upcycled designs need to look good. Otherwise “fans won’t buy it. It’s as simple as that. The real impact comes when sustainability is aspirational, collectible and desirable, not something people buy out of guilt.”

And that’s the beauty of upcycled football kits – not only are they good for the environment, they look beautiful too. Who knows, maybe I’ll upcycle my Walthamstow FC shirt back into a William Morris wallpaper?

3 weeks ago

23

3 weeks ago

23