The last time Joregelis Barrios heard from her brother Jerce, the call had lasted just one minute.

Immigration officials had moved Jerce from the detention center in southern California where he had been for six months to another one in Texas. He sounded worried, as if he had been crying. He told his sister he might be transferred somewhere else soon.

No one has heard from him since.

Within hours of that call, Jerce was forced on a plane to El Salvador and booked into the country’s most notorious prison: the Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (Cecot). He was one of more than 260 men that Donald Trump’s administration had accused of terrorism and gang membership. His sister thought she recognized him in the videos shared by the Salvadorian government, among the crowd of deportees with shaved heads and white prison uniforms, being frogmarched to their cells by guards in ski masks. Then CBS News published a leaked list of the deportees’ names, confirming her worst worries.

“It was a shock,” said Joregelis. “Jerce has always avoided trouble.”

Jerce, a 36-year-old professional soccer player and father of two, had come to the US last year to seek asylum, after fleeing political violence and repression in Venezuela.

An immigration hearing to review his case was scheduled for 17 April, just weeks after he was abruptly exiled to El Salvador.

“He was so optimistic, up till the last day we spoke,” said Mariyin Araujo, Jerce’s ex-partner and the co-parent of his two daughters, Isabella and six-year-old Carla.

“He believed the laws there in the US were the best, that it would all work out soon,” she said. “How far did that get him?”

Barrios was flown to Cecot on 15 March. For the past two months, his family has been obsessively scanning news updates and social media posts for any sign that he is still alive and healthy. They have been closely monitoring the court cases challenging Trump’s invocation of the wartime powers of the Alien Enemies Act against the Venezuela-based gang known as Tren de Aragua, to exile immigrants – most of whom have no criminal history – to one of the most notorious prisons in the world. And they have been wondering what, if anything, they can do for Jerce.

In Machiques, a small town near Venezuela’s border with Colombia, locals have painted a mural in Jerce’s honor. His old soccer club, Perijaneros FC, started a campaign demanding his release – and children from the local soccer school held a prayer circle for him. “We have created TikToks about him, we have organized protests, we held vigils,” said Araujo.

“We have looked for so many ways to be his voice at this moment, when he is unable to speak,” she said.

But as the weeks pass, she said, she is increasingly unsure what more she can do. The Trump administration has doubled down on its right to send immigrants to Cecot, despite a federal judge’s order barring it from doing so.

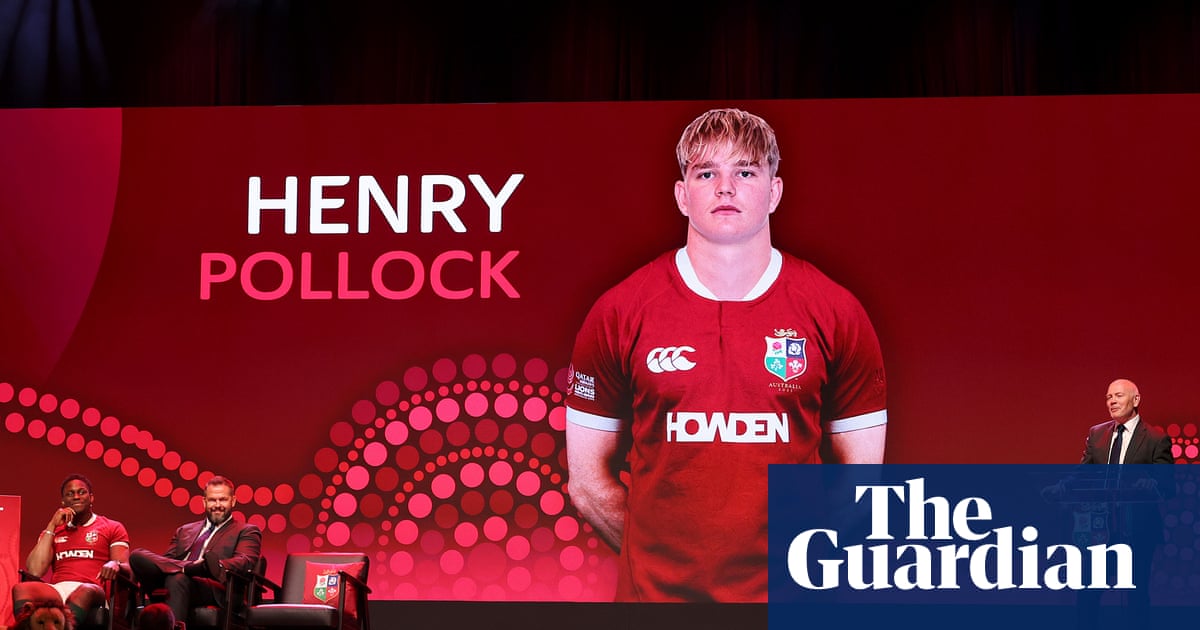

To justify these extraordinary deportations, both Trump and El Salvador’s president, Nayib Bukele, have publicly insisted that the men sent to Cecot are the worst of the worst gang members. To mark Trump’s first 100 days in office, his Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released a list of “Noteworthy individuals deported or prevented from entering the US” – and characterized Jerce as “a member of the vicious Tren de Aragua gang” who “has tattoos that are consistent with those indicating membership” in the gang.

Jerce’s family and lawyer say the only evidence DHS has shared so far is that he has a tattoo on his arm of a soccer ball with a crown on top – a tribute to his favorite soccer team, Real Madrid. His other tattoos include the names of his parents, siblings and daughters.

“My brother is not a criminal,” Joregelis said. “They took him away without any proof. They took him because he’s Venezuelan, because he had tattoos, and because he is Black.”

She’s still haunted by the strange sense of finality in his last call. He had asked after his daughters, and whether his Isabella had been eating well. “I told him she had just had some plátano,” Jorgelis said. “And then he said to me: ‘I love you.’ He said to tell our mom to take care.”

Araujo has struggled to explain to her daughters why their father hasn’t been calling them regularly. She lives in Mexico City with Carla, her six-year-old. Isabella, three, is in Venezuela with Jorgelis.

Carla, especially, has started asking a lot of questions. “Recently, she said to me: ‘Mom, Dad hasn’t called me, Mom. Could it be that he no longer loves me?’” Araujo said. “So I had to tell her a little bit about what had happened.”

Now Carla cries constantly, Araujo said. She misses her father, she misses his scrambled eggs, she misses watching him play soccer. She keeps asking if he is being treated well in detention, if he is eating well. “It’s too difficult,” Araujo said. “From a young age, kids learn that if you do something bad, you go to jail. And now she keeps asking how come her dad is in jail, he’s not a bad person. And I don’t know how to explain. I don’t know how to tell her there is no logical explanation.”

Jerce had been in detention of some sort ever since he set foot inside the US.

Last year, he had used the now defunct CBP One app to request an appointment with immigration officials at the border. After more than four months of waiting in Mexico, agents determined that he had a credible case for asylum – but decided to detain him in a maximum-security detention center in San Ysidro, California, while he awaited his hearing.

“Jerce didn’t tell us much about what it was like there, because he didn’t want us to worry,” said Jorgelis. “The only thing he did say was, why did he have to be Black? I believe he faced a lot of racism there.”

When he first arrived at the border, immigration officials had alleged he might be a gang member based on his tattoos and on social media posts in which he was making the hand gesture commonly used to signify “I love you” in sign language, or “rock and roll”.

His lawyer, Linette Tobin, submitted evidence proving that he had no criminal record in Venezuela, and that his hand gesture was benign. She also obtained a declaration from his tattoo artists affirming that his ink was a tribute to the Spanish soccer team and not to a gang. Officials agreed to move him out of maximum security shortly thereafter, in the fall of last year. “I thought that was a tacit admission, an acknowledgement that he’s not a gang member,” Tobin said.

When officials moved him to a detention center in Texas, Tobin worried that transfer would complicate his asylum proceedings. Since she is based in California, she wasn’t sure whether she’d be able to continue to represent him in Texas.

Jerce had been worried when Tobin last spoke to him on the phone, in March, but she had reassured him that he still had a strong case for asylum. Now, the US government has petitioned to dismiss Jerce’s asylum case, she said, “on the basis that – would you believe it – he’s not here in the US”.

“I mean, he’d love to be here if he could!” she said.

Other than ensuring that his case remains open, Tobin said she’s not sure what more she can do for her client. After the ACLU sued Donald Trump over his unilateral use of the Alien Enemies Act to remove alleged members from the US without legal process, the supreme court ruled that detainees subject to deportation must be given an opportunity to challenge their removals.

But the highest court’s ruling leaves uncertain what people like Jerce, who are already stuck in Salvadorian prison, are supposed to do now. As that case moves forward, Tobin hopes the ACLU will be able to successfully challenge all the deportations.

But in a separate case over the expulsion of Kilmar Ábrego García, whom the administration admitted was sent to Cecot in error, the supreme court asked the administration to facilitate Ábrego García’s return to the US – and the administration said it couldn’t, and wouldn’t.

In his last calls with his family, Jerce told them he’d be out of detention soon – that it would all be better soon. Once he was granted asylum, he said, he would try to join a soccer league in the US and start earning some money. He had promised Carla he’d buy her a TV soon.

Now, Araujo said: “I don’t even know if he is alive. We don’t know anything. The last thing we saw was a video of them, and after that video many speculations, but nothing is certain.”

3 hours ago

5

3 hours ago

5