Jokes have a specific relation to Trumpian politics: they are the tip of the spear for introducing illegal or once-unacceptable ideas to the public, under a thick gloss of irony or plausible deniability, to advance a far-right agenda.

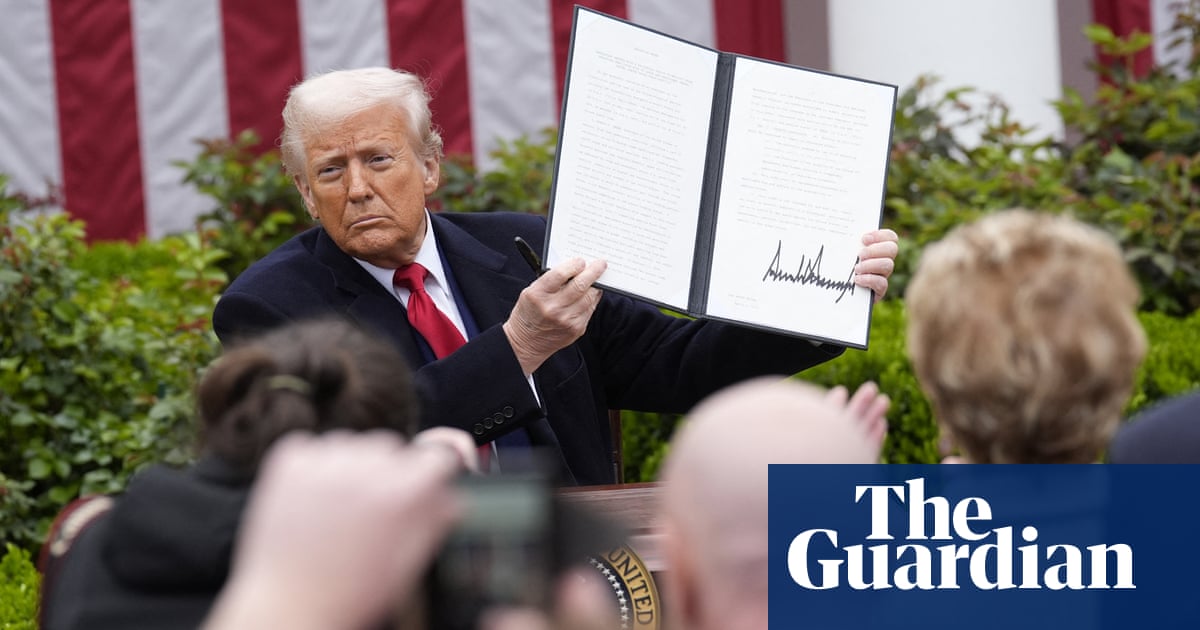

In 2016, Donald Trump’s support from the young, online “alt-right” was underestimated in part because so much of the profession of love for Trump, and for his racist and authoritarian ambitions, came in the form of supposed jokes. Trump himself, meanwhile, uses humor to charm and titillate, making jokes to demean adversaries, get audiences on his side, and hint, with winking coyness, about his next move. This has been his strategy for years.

So when analysts have asked, over the years he has been floating the possibility, whether Trump is joking or serious when he has said that he will seek a third term in office, in defiance of the constitution, the answer was never an either-or. The answer was “yes”: he was both joking, of course, and he was also entirely serious.

For those who still had not caught on to this game, Trump made himself helpfully explicit this week, in an interview with NBC News. “I’m not joking,” he said, when asked to clarify his ambitions to continue in office in violation of the 22nd amendment. “There are methods which you could do it [sic].” He acknowledged that he could possibly run as a vice-presidential candidate – in potential violation of the 12th amendment – and assume office once the presidential candidate on his ticket stepped aside, as one possible way to hold onto power. “But there are others, too,” he said. He refused to elaborate on what those other methods might be.

Constitutional lawyers – a group of people who seemingly cannot help but indulge in clever games of wordplay even when the republic is at stake – seemed to take up Trump’s anti-constitutional authoritarian ambitions as something like a fun intellectual challenge.

“Anyone discounting a 3d Trump term per the 22d am + the 12th am is thinking magically,” wrote Larry Tribe, of Harvard Law, on Bluesky. “The 22nd dsn’t bar *serving* a 3d term, only being *elected* 3 times. The 12th dsn’t bar running for VP unless ‘ineligible to serve as Pres, but Trump isn’t ineligible. QED! [sic.]’” This is more or less what the Trump supporters seem to be saying: that somehow, the plain meaning of the 22nd amendment – to prevent a dictator from seizing permanent control of the presidency – is not in effect – at least, not if Trump performs a sufficiently clever formal trick, something like the legal equivalent of a drunken dancer bending over backwards while proceeding underneath a limbo stick. In the event that that doesn’t work, Andy Ogles, a Republican representative from Tennessee, has introduced a bill that would nullify the 22nd amendment for Trump’s purposes – just in case.

But the wordplay and logical twisting that is taking place should be understood as pretextual, and completely irrelevant to what Trump is actually doing by declaring his intention to stay in office. Trump does not care about meeting the requirements – technical or substantive – of the 22nd amendment. That is because he does not care very much about the constitutional limits on his authority and will at all. Trump already considers himself a dictator. What he is saying, when he declares his intention to illegally run again, is not that he could find a way to do it that is plausibly legal. He is saying, instead, that the law does not apply to him. Trump is declaring that wherever the constitution contradicts his desires, the constitution is moot.

The Trump era has already been one of dramatic constitutional disintegration – one that his own accumulation of power and disregard for the law has accelerated but did not incite. The principle of popular sovereignty has been eroded by the US supreme court’s systematic gutting of the 1965 Voting Rights Act – which has made voting more onerous, particularly for racial minorities and groups that tend to vote Democratic – and by their 2010 decision in Citizens United v FEC, which opened a floodgate of money into politics and allowed billionaires and other monied interests to manipulate the political process to their benefit.

Congress’s scleroticism and stagnation have made the legislative body into little more than a media platform: Senators and representatives can use their notoriety and sometimes their subpoena power to make a point, but they are rarely in a position of making policy. Instead, much of the work that would have once been called legislating is now done by the federal courts, and by the executive. And that executive’s power and prerogatives have expanded far beyond what is imagined by the drafters of article II – now carrying sweeping powers to pursue military acts of aggression abroad and a novel new impunity from prosecution for illegal deeds committed at home. The president – at least with Donald Trump – now looks like something much closer to a king, with the supreme court serving as something like a counsel of scheming viziers or gossiping court eunuchs.

Under such conditions of constitutional rot, it seems almost inevitable, in retrospect, that a failure to grasp the failures of the American political system would lead to the emergence of a strongman dictator. But one need not take such a long view of history to see the obvious truth that Donald Trump does not think that he should have to leave office just because the law says so.

One can look, instead, to recent history. After all, we already know what happens when Trump is supposed to leave the presidency: he holds onto it, refusing to go and encourages violence to try to get his way. Just because the attempted putsch did not work on January 6 does not mean that it did not signal a core feature of his theory of his own power: that any attempt to take it from him, be it by law or by custom or by the ballot box, is illegitimate. The 22nd amendment is hardly the first law that Trump has ignored in pursuit of this principle. He has never been a law-abiding man before. Why should we expect him to start now?

-

Moira Donegan is a Guardian US columnist

23 hours ago

4

23 hours ago

4