In the classic dinner-party scene in the film Notting Hill, Tim McInnerney’s character promises a brownie to “the saddest act here”. In response, the guests (including the glamorous movie star played by Julia Roberts) try to outdo each other with tales of their painful suffering and pathetic failures.

In our gloomy autumn of 2025, western democracies could play quite a convincing version of this game. There is the depressed United Kingdom, where Keir Starmer’s approval ratings have fallen to record lows and Reform leads in the polls. There is the deeply broken United States, where a supine opposition seems incapable of preventing Donald Trump from chopping away one guardrail after another of our constitutional order. There is Spain, where this summer a Socialist party scandal threatened to topple the fragile minority government of prime minister Pedro Sánchez.

But as winter approaches, it might seem as if France deserves the brownie. Its government has limped along in a state of paralytic ineptitude since a disastrous snap election in July 2024 produced the mother of all hung parliaments. Since then, Emmanuel Macron has gone through five prime ministers (counting poor Sébastien Lecornu’s second go-round), while his own popularity hovers around a disastrously low 20%, and dropping. Two-thirds of the French see politicians as fundamentally corrupt, and as apparent proof of this belief, former president Nicolas Sarkozy reported for prison this week to begin serving a five-year sentence for campaign finance violations. Meanwhile, the public deficit is expected to rise to a dangerous 5.4%, leading to the downgrading of France’s credit rating.

The French public is still reeling from the trial of Dominique Pelicot and the more than 50 men whom he allowed to rape his drugged and unconscious wife, which was widely seen as symbolising a dire national failure to address the abuse of women. And as if all this weren’t enough, on Sunday morning thieves brazenly broke into the Louvre and, in a humiliating security failure for the government, made off with millions of euros worth of France’s crown jewels.

Small wonder that in a new poll, fully 90% of the French believe that the country is in decline.

And, since despondent moods tend to build on themselves, events that might otherwise be taken as incidental (the Louvre break-in) or as demonstrating the strength of republican institutions (Sarkozy’s jailing), instead have been widely cited as further evidence of national decadence.

Small wonder then that the bleak mood has driven so many voters into the arms of the far right – in this case, the National Rally of Marine Le Pen. As Americans know well, alluringly simplistic stories of great nations laid low by feckless elites and unchecked immigration tend to play very well with older white voters who feel economically blocked and socially disdained. Polls show that in new parliamentary elections, the National Rally would far outpace its nearest competitor. Macron has not helped matters with his haughty insistence that, despite last year’s electoral defeat and the catastrophic polling, his office not only gives him the right to impose unpopular policies, but to lecture the French on their shortcomings when they object.

There’s no denying the depth of the problems, yet there are still reasons to question whether France is heading into violent catastrophe, or just dealing with a series of grave, but still relatively ordinary, crises.

For one thing, diagnosing national decline and blaming it on a kind of pervasive moral rot is practically a French national sport. The practice goes back at least to the 1760s, when defeat in the seven years’ war, and the loss of much of the colonial empire, provoked anguished debate about the population’s supposed lack of patriotic fervour compared to that of the hated English. After Napoleon’s defeat, a generation of writers worried that France’s days of glory and splendour lay in the past. In the mid-19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville criticised his countrymen for submitting to “soft despotism”, and in the midst of the second world war, the great historian Marc Bloch blamed France’s “strange defeat” in large part on the corrosive divisions of the interwar years. More recently, French bestseller lists have featured titles such as La France Qui Tombe (The France That Falls) and Le Suicide Français (The French Suicide). It’s also worth noting that the first book to bear the title The Decline of France was published in 1842.

But despite all this breast-beating, the country has often shown unexpected resilience in the face of crisis. Earlier in this century, after the large-scale 2005 riots by youths, many of them Muslim, in the miserablesuburban cités, many French writers predicted imminent social breakdown or worse. Drawing on them in 2014, the British academic Andrew Hussey published a controversial book called The French Intifada. Yet more than a decade on, his dire predictions have not come to pass, and the French Muslim population remains on a path – difficult and terribly uneven, but a path nonetheless – of integration into French society. Hussey himself has just published a new, equally pessimistic book entitled Fractured France: A Journey through a Divided Nation, but tellingly focuses as much on the disaffected white working class as on Muslims.

France today is unquestionably divided, giving rise to enormous pain and anger. But at the same time, it is worth asking how deep the divisions actually extend, in comparison both to the past and to what exists elsewhere.

after newsletter promotion

In the century after the French Revolution, the country was also divided, and the divisions ran deep indeed. Should the country be a monarchy or a republic? Should the Catholic church be the state religion, with control over the educational system? Should the state strive to redress social inequalities? In 1820, the historian Augustin Thierry called France “two nations on the same soil, two nations at war in their memories and irreconcilable in their hopes for the future.” During the revolution of 1848, the Paris Commune of 1871, and the second world war, civil strife took tens of thousands of lives.

Today, France again roils with anger, from the Muslim-majority banlieues of Paris and Marseille to the white working-class redoubts of the Pas-de-Calais. But the anger stems above all from a sense of being left out, abandoned by the state and arrogant social elites (both embodied all too well by Macron), rather than from fundamental disagreements over the proper organisation of the state and society. Large majorities favour the maintenance of the social safety net (including national health insurance), gender equality, abortion, birth control, gun control, secular public schooling, and respect for science. The single issue that has cost Macron the most support was his attempt (now suspended) to raise the retirement age by two years. Opponents cast it as a neoliberal betrayal of French workers, but it was an adjustment to the social safety net, not a full-scale repudiation.

Compare this situation to the one in the US, where the ferocious polarisation of recent years corresponds to much deeper cultural and ideological divisions. The Maga Republicans want to gut the central government to an extent utterly unimaginable in France. They want to ban abortion and restrict access to birth control, allow virtually unlimited gun ownership in the name of personal freedom, challenge the authority of medical science and reintroduce religion (meaning Christianity) into public classrooms. Democrats (and a substantial portion of the general population) oppose these moves.

France still faces enormous challenges in the coming year. It is hard to imagine Macron finding a way out of the current political impasse, and while he adamantly promises to remain in office until the end of his term in 2027, an inability to pass a budget by the end of December, or additional votes of no confidence could yet force his resignation (which 70% of the population desires). And it is widely expected that, after Macron, the National Rally will finally come to power.

Even so, I have confidence, born out of many years observing the country, that things will not go as badly for the French as the French themselves predict. When it comes to the prize for the “saddest act” among the western democracies, I still think the US deserves the brownie.

-

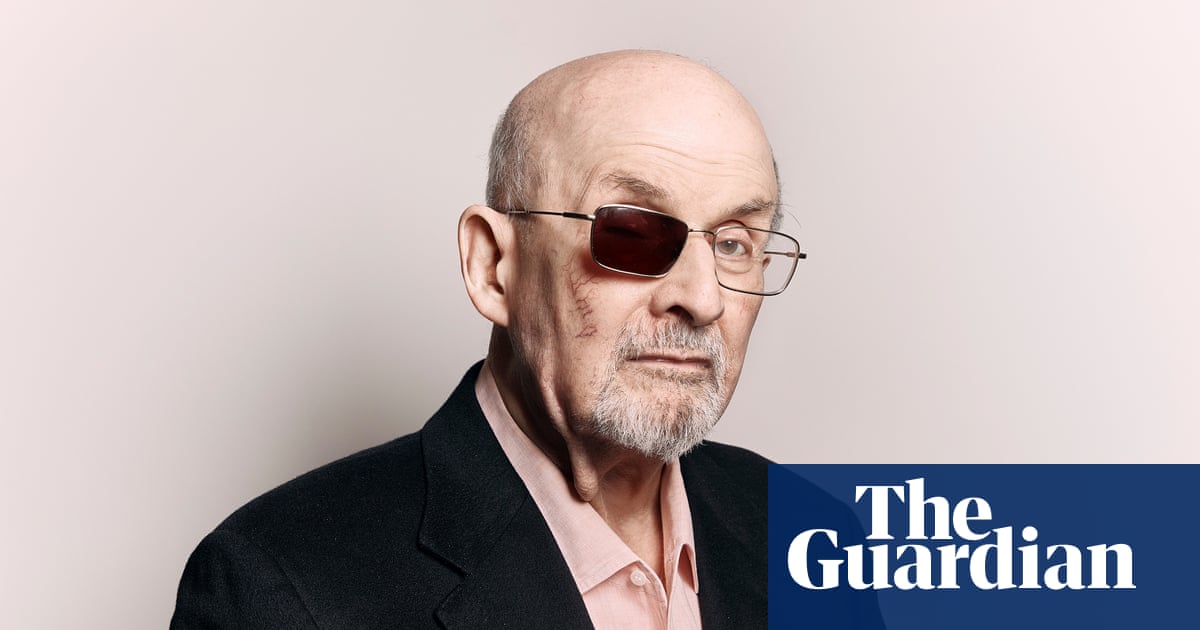

David A Bell teaches French history at Princeton. His books include Men on Horseback: Charisma and Power in the Age of Revolutions

3 months ago

64

3 months ago

64