From the reinforced windows of ward five, high up in the Edwardian eaves of London’s Royal Waterloo hospital for children and women, a 14-year-old Celia Imrie used to stare down, hoping to spot her mother. “When I walk past that old, redbrick hospital building today, on my way to the Imax or the National Theatre,” says Imrie, who went on to become a successful actor, “I can see the window where I’d sit waiting for her and a deep chill passes through me.”

Every day, thousands of commuters and tourists pass beneath the former hospital. Some might look up to admire the terracotta facade, with its ornate colonnades and glazed tile lettering, but few are aware of the medical horrors that took place in one small room on the top floor: the Sleep Room. It was here, on ward five, that female patients – they were almost always women – were put to sleep for three to four months (in one case, five), only roused from their beds to be fed, washed and given electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a shock of up to 110 volts that passed bilaterally through the temporal lobe of the brain, triggering a grand mal seizure.

Almost 60 years on, Imrie and other former patients want to know why they were subjected to such extreme treatments without consent. “My father was absolutely shattered when he saw me,” remembers Anne White of her time in the Sleep Room. “He said I just looked like a walking zombie.” Shelley, who worked as a nurse on ward five for six months in 1968, recalls the patients’ glassy skins. “They had this dozy, greasy sheen to them. They were like people you just don’t see. We knew them all, but not at all really.”

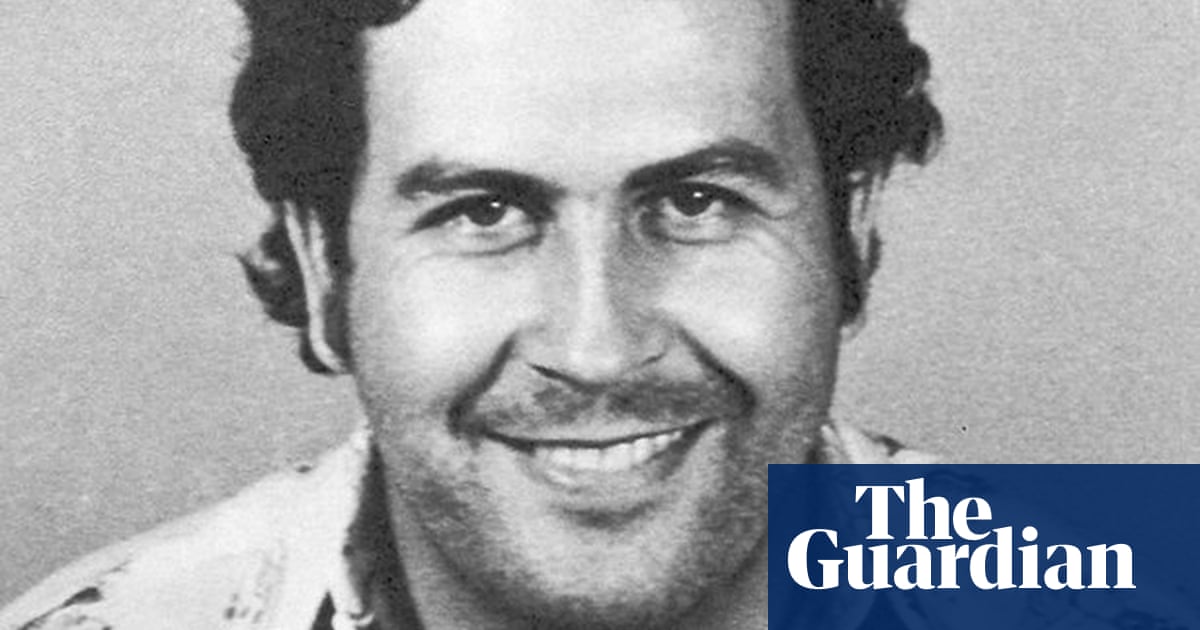

The Royal Waterloo became part of its more famous neighbour, St Thomas’ hospital, in 1948, the year the National Health Service was formed. It was an important year for William Sargant, too. An ambitious 41-year-old doctor, Sargant was appointed the physician in charge of the department of psychological medicine at St Thomas’, one of the world’s most prestigious teaching hospitals. It wasn’t long before ward five, a psychiatric unit for inpatients, was being referred to as the William Sargant ward. It was Sargant’s personal fiefdom, a place where he could pursue, unchecked, his own mechanistic approach to psychiatry: the brain, like any other organ or limb, was best fixed with physical treatments, he believed. If it was damaged, it first needed to be “splinted”.

Not for Sargant the couch-based therapists who had dominated psychiatry in the early 20th century. It was, in the words of one of his heroes, Lord Moran, personal doctor to Winston Churchill, time to “cut the cackle” and allow psychiatry, for so long seen as a Cinderella speciality, to take its rightful place in the medical mainstream. And deep-sleep therapy, or continuous narcosis, was his most notorious procedure.

Sleep has long been recognised as a way to calm the distressed – the “balm of hurt minds”, as Shakespeare called it in Macbeth – but for Sargant it had another use. The Sleep Room allowed him to administer treatments that his patients might not otherwise agree to, such as intense courses of ECT. Informed consent was implicit rather than sought – the wishes of desperate relatives were often sufficient. “I am not sure consent forms were in abundant use in the 60s,” remembers one medic who worked on ward five in 1968 and wishes to remain anonymous. “In those days, doctors rarely discussed the risks associated with treatments.”

Narcosis combined with ECT, Sargant believed, broke up set patterns, or circuits, of behaviour, and reprogrammed disturbed minds with more positive thoughts. A factory reset. But for many it was a terrifying ordeal that destroyed memories and left them wrestling with existential crises of identity. “As a rule, the patient does not know how long he has been asleep, or what treatment, even including ECT, he has been given,” Sargant said. “Under sleep … one can now give many kinds of physical treatment, necessary, but often not easily tolerated.”

Few people had the courage to stand up to Sargant. He belonged to an era of unfettered medical authority, when doctors, particularly male consultants, exuded a sense of droit du seigneur. They were treated like gods, by colleagues as well as by patients, breezing through swing doors, minions trailing behind them.

“He still features in my nightmares,” Imrie says today. “There was a whiff of sulphur about him,” said the late Malcolm Lader, emeritus professor of clinical psychopharmacology at King’s College London. He wore immaculate chalk-stripe suits (never a white coat), whether he was presenting TV programmes on the BBC, conducting his rounds, or making frequent trips across the Atlantic to lecture about Battle for the Mind, his bestselling book on brainwashing. Over 6ft tall, he was an imposing physical presence, on the wards as well as the rugby pitch. “If he’d been a gorilla, he would have been one of those huge male silverbacks,” says Henry Oakeley, Sargant’s registrar in the 1960s.

Sargant had administered narcosis to traumatised soldiers in the second world war, but admitted it was “not without its dangers”. He only started to champion the treatment again in the 60s, when one of his registrars, Chris Walter, noticed that if patients were treated with ECT, antidepressants and narcosis, they did better than those who were just given ECT and antidepressants. As was so often the case in psychiatry, no one was quite sure why. But patients were now sent to the Sleep Room instead of being lobotomised – they would only go under the knife if narcosis failed. The Sleep Room, in other words, had become a last-chance saloon.

Behind the medical rationale, however, the Sleep Room served a more sinister purpose. As the 60s started to swing and Sargant’s reputation soared, middle-class parents sent their wayward daughters to him for moral correction. In the mid-60s, for example, a wealthy businessman contacted Sargant, explaining that his daughter had fallen in love with an “unsuitable” local man in Europe and wanted to marry him. Could Sargant help? A photo later emerged of Sargant, the father and a heavily sedated daughter standing at the door of the aeroplane that had returned her to the UK. “Basically, Sargant brought this attractive young woman back at the end of a needle,” recalls a retired professor, who was a student at St Thomas’ at the time.

In the past 15 years, online communities websites such as William Sargant at the Royal Waterloo Hospital have tried to bring survivors together to tell the world what happened to them. It hasn’t been easy. Some of the medical records of patients who passed through the Sleep Room, including five who died, have disappeared or been destroyed, fuelling conspiracy theories that Sargant had been conducting experiments on behalf of the intelligence services. And there is still a stigma attached to mental illness. Patients are often reluctant to tell their story, one comparing the shame of her time in the Sleep Room to admitting to a stretch in prison.

Sargant’s surviving patients believe he represented the epitome of patrician arrogance, echoing the way men have, throughout history, exerted control over women’s bodies. Suffering from a range of eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder and anxiety, as well as postnatal depression, many were in their teens or early 20s during their treatment, which means they are now in their 70s. Sixty-year-old recollections can be unreliable, particularly those dimmed by repeated electric shocks and large doses of drugs. And there are those who will argue that memories set down while thoughts are distorted by mental illness are not real and should not be trusted. But the brain is a resilient organ. Sargant underestimated its plasticity, its resistance to being permanently “repatterned”. And now his patients, for so long neither heard nor believed, are ready to tell their story.

‘I used to gaze at the dead-looking women lying on the floor on grey mattresses, silent’

Celia Imrie

My poor mother used to come and visit me every day when I was an anorexia patient on ward five at the Royal Waterloo. It was 1966 and I was only 14 at the time. There were moments when she sat down beside my bed and I didn’t even know who she was. At other times, they wouldn’t let me see her because I was still struggling to eat my midday lunch at 2.30pm. It was like being in a prison camp. They are horrible memories, as you can imagine, and sometimes I struggle to recall exactly what happened.

I was brought up in Guildford, the fourth of five siblings. My mother was a true-blue aristocrat; my father was born in a tenement block in Glasgow. He went on to become a successful doctor, dentist and radiologist, who worked at the Royal Surrey County hospital in Guildford. I think it was embarrassing for him to have a daughter who starved herself.

I was put on heavy medication as soon as I arrived on ward five. Three doses of liquid Largactil daily. I can remember the tumbler cup quite clearly. The side‑effects were startling. My hands shook uncontrollably for most of the day, and I’d wake up to find clumps of my hair on the pillow. But the worst consequence was that everything I saw was in double vision. When Sargant came into the room, there were two of him. It was horrific.

I was injected with insulin every day, too. Sargant was a big believer in fattening up his patients to get them well, and you soon put on weight with insulin. I think I had what was called “sub-coma shock treatment” – you weren’t given enough insulin to induce a hypoglycaemic coma, but it was enough to make you drowsy, weak, sweaty and hungry.

Some years back, I tried to find my hospital records, to see the details of my treatment. Unfortunately, Sargant seems to have taken away a lot of his patients’ records, including mine, when he retired from the NHS in 1972. Either that, or they were destroyed. I can’t remember ECT happening to me, but I can remember it happening to others.

At one point during my stay I shared a room with another woman and I witnessed her having electric shock treatment right next to me. I vividly recall every sight, sound and smell. The huge rubber plug jammed between her teeth; the strange, almost silent cry, like a sigh of pain, she made as her tormented body shuddered and jerked; the scent of burning hair and flesh. It was a terrible thing for a 14-year-old to witness. Afterwards, Sargant came into our room and said in front of the woman, “Well, if we hadn’t caught her, she would have been out of the window.”

The Great Man was very grand when he came on his ward rounds, tall, with an evil presence. The other doctors and nurses all bowed and scraped – they were in thrall to this self-appointed god of psychiatry. He was brusque and cold, and he never talked directly to you. Instead he issued orders over your head, talking about “this one” and “that one”. But that was preferable to making eye contact with this proud, incorrigible man with his hard, dark eyes.

I remember having to go over to St Thomas’ hospital and be paraded in front of a theatre full of students as part of one of Sargant’s “grand round” presentations. He was there in the middle of everyone, with me, addressing a group of medical students. I can’t remember exactly what Sargant said, but I suspect he boasted about the insulin I was being given – and possibly the electric shocks. I had to take my clothes off because the students had to see how thin I was.

Being taken to the loo is another memory – I clearly wasn’t able to walk on my own. And at some point I went down the end of the ward to look at the Sleep Room. I used to peer through the portholes in the swing doors and gaze at the dead-looking women lying on the floor on grey mattresses, silent, in a kind of electrically induced twilight. I can remember the distinctive smell, too – the smell of sleep.

I can’t be sure if I ever spent any time inside that room, but I can picture it so clearly. And, although I saw many female patients come back to the ward from there, I never saw anyone emerge from the place awake. You went in asleep and you came out asleep, and you were totally unconscious while inside. So you wouldn’t necessarily be aware that you’d had the treatment. Today, I must accept the very real possibility that I was taken there. Certainly the insulin treatment that I received was often a precursor to narcosis. Like the electric shocks, I have to assume that it might have happened to me, even though I can only recall it happening to others.

I do know that lobotomy – or leucotomy, as the doctors called it – was a very real threat. I distinctly remember patients on the ward with big bandages on their heads, barely able to walk.

Many years later, I went with friends to see Coma. It is a second-rate film starring Michael Douglas and Geneviève Bujold, in which Bujold discovers a ward full of patients suspended in hammocks in drug-induced comas. When we came out into Leicester Square in London, my friends were laughing at the silliness of the plot, but I had the shakes and it took me some days to recover. They probably thought I was coming down with something. In fact, it wasn’t until much later that I realised why that film had upset me so deeply.

Sargant continues to cast a long shadow over me, 60 years later. Even today, I can still see his face so clearly; his ape-like features. And sometimes I go to the depths of despair for no real reason. Most of the time I manage to pull myself out of it, but there’s no question that Sargant damaged me in some way.

‘Waking up after a dose of ECT was absolutely terrifying. I didn’t even know who I was’

Mary Thornton

My memories of ward five are a series of detached snapshots. Electrodes attached to the side of my head; being given a general anaesthetic; seeing an image of myself in the mirror one day, a strange face staring back at me. It was early 1971 and I was barely 20. I understood that I was being treated for an acute anxiety state. And, as part of that treatment, Dr Sargant would give me continuous narcosis to help my head have a nice long rest.

after newsletter promotion

Initially, I stayed in a single room along a narrow corridor. Ward five was mostly for female psychiatric patients, but I can distinctly recall a tall, thin man wandering up and down, singing Hello, Dolly! endlessly. I was given ECT soon after my arrival. I was also given Largactil – we used to call it the liquid cosh – and Haldol, another antipsychotic.

My parents used to bring me cigarettes, and I was allowed two during meals. There was never enough time to smoke those damn things. I remember the baths, too, because the doors had a horrible peepy hole in them so that the nurse could take a look at you while you were having a bath.

In the early days, my boyfriend John would come and take me out for a walk on the Embankment. One day, he came in and I didn’t recognise him. I had no idea who he was. The ECT and drugs had destroyed my memories of him. He was so upset that he stormed into the Great Man’s office to confront him. Reaching across Sargant’s desk, he tried to strangle him, shouting, “What the fuck have you done to my girlfriend?” Sargant must have pressed a panic button, because John was grabbed by two beefy orderlies, who threw him out on to the Embankment and told him never to return. After that, I forgot all about John until much later.

It was then, I think, that Sargant decided it was time to move me into the Sleep Room. During narcosis, we slept continuously, only woken every six hours for meals, washing and toileting. We were also given an anaesthetic followed by ECT, but I have no memory of this – it’s what I’ve since read and been told. As for the Sleep Room itself, I can clearly recall the darkened ward. I can remember the smell. The stink. There were six divan beds, low on the ground. I was in the one on the left-hand side.

I was on ward five for 12 weeks in all, and received ECT throughout my stay there. Waking up after a dose of it was absolutely terrifying. I felt complete and utter terror because I didn’t even know who I was, or what my name was … I remember rubbing my temples and feeling these sort of dry salt patches where they had put the electrodes on either side of my head. Apparently, Sargant used to give it to people in my state at least twice a week, so I could have had as many as 24 shocks. I can’t be certain, though, as my memory was obliterated by the treatment. I have tried in vain to track down my records. For six to eight of those 12 weeks, I was in the Sleep Room. I remember the end of my bed being up on bricks, and some kind of enema being dripped in very, very slowly. What was that all about?

Incredibly, Sargant only lost five of his patients through his inhumane narcosis treatment. But there must have been patients with other complications, intestinal ones, for example, if they were kept asleep, without exercise, for months on end. In later life I certainly had horrible problems with my gut, and with various obstructions, which led to me losing half my bowel and ending up with an ileostomy, where your small intestine is brought through an opening in the abdomen to allow waste to exit. I can’t help feeling that my time in the Sleep Room is at least partly responsible for my subsequent medical problems.

One memory of the Sleep Room that I used to think was false and imagined, but I now know to be true, was that if the ECT and narcosis were to fail, I would be given a lobotomy. That would be the next course of treatment for me. I was absolutely terrified at the prospect. I had it in my head that this was going to happen if I didn’t pull my socks up, and fast. They had tried to persuade me to visit occupational therapy. I hated stuff like making baskets and fiddling around with bits and pieces. But then I thought, if I don’t play ball, I’ll never get out of this place. I have no recollection of leaving there after three months, or who came to get me, or anything.

After I was released, I was sent to my eldest brother in Yorkshire. He was a dentist and had five children at the time. One day, while staying there, I suddenly remembered there was someone in my life called John. I must have found his phone number in my luggage or something. I rang him and said, “Can you meet me at King’s Cross station?” It must have been a big shock for him because he’d been told I’d never come out of hospital. Thankfully, I recognised him, and six months later we decided to get married. We brought up four children in Brampton, Cumbria, and I went on to run an antique shop from my house before going into teaching. Sadly, John died in June 2021 after many years of fighting cancer. I miss him dreadfully.

Anxieties have haunted me for most of my life, but I don’t get depressed. And I’ve always had an interesting relationship with food – it’s a lot better now than it used to be. But I can’t deny that I have had a life of pain since I left the Sleep Room. For over 15 years, I was addicted to fentanyl. That’s another story, and one that’s made me angry for a long time.

‘I remember a block of rubber being placed in my mouth and jelly rubbed into my temples’

Linda Keith

I was a wild child of the 60s, and from a ridiculously young age I’d had a passion for R&B music. I first met Keith Richards when I was 17 and he was 19, and he wrote the song Ruby Tuesday about me after we’d split up. As a model, I worked with all the great fashion photographers of the time, including David Bailey. By the time I met Jimi Hendrix, in 1966, drugs had become a big part of my life. Within a year, I had become a detached and elusive spectre.

My parents always referred to me as “being ill” rather than the more accurate description of me: a pleasure-seeking, music-obsessed drug addict. What they wanted was a tame, house-trained lapdog. They couldn’t face my real afflictions, which is why, in early 1969, when I was 23, they sought out completely the wrong person to cure me: Dr William Sargant.

My parents drove me past his house on Hamilton Terrace in St John’s Wood to persuade me what a great man he was. They even gave me his book – as if, by reading it, I’d consented to his treatments. I couldn’t read a page, and refused to see him. No way was I going to be violated by his brutal methods, but my parents had already contacted him, describing me as being ill with depression.

I wanted to sort myself out in my own way, but I knew it would take a great deal of soul-searching. Going cold turkey at some point was also inevitable. I didn’t want to do it just yet, so I went out to score – one more time. When I returned, I headed straight up to my bedroom and got myself high. Everything was fine and then the peculiar sensations began. My head felt enormous, full of fluid, red and bloated, my eyes seemingly popping out of their sockets. Then I had a fuzzy feeling, like pins and needles, and my tongue started to feel too large for my mouth. And then I realised that I was struggling to breathe. I phoned 999 but couldn’t talk, so I had to find my parents for help. I put a towel over my ridiculously elongated tongue and grunted at my parents as I handed over the phone. The paramedics gave me a shot of something, and the facial paralysis weakened. My tongue went back to its normal size, too. I agreed, in my terrified state, to see Sargant.

My parents arranged for me to be admitted to ward five under his care. I have no memory of getting there or of being put to sleep in his Sleep Room. All I know is that I didn’t wake up for six weeks. My memories are necessarily patchy, dim recollections from when I was woken up to be fed, washed or be given ECT. The room was in almost complete darkness, except for a small pool of light from a dim lamp. It was eerie. Silence, apart from the moan of sleeping patients, as many as eight of us crammed close together. I was in the first bed on the right, behind the door.

We were woken every few hours to go to the loo and be fed. It was a twilight world, and I have a tinge of fear even now as I force myself to think about the enormous amount of ECT that I was given. I have no idea how they dealt with my withdrawal from drugs. I’m guessing that the cocktail of medication they gave me to put me to sleep tempered my physical withdrawal symptoms. I had no understanding of what was going on or being done to me. Time didn’t exist. I had been rendered completely helpless, but I was strangely aware of my helplessness at some unconscious level.

After my narcosis treatment, I was taken from the Sleep Room to a small room on ward five overlooking Waterloo Bridge. My memory of these few months is also limited – just vague impressions. But I do remember being taken in a van with other patients over to St Thomas’ to have ECT twice a week. It was the same anaesthetist every time: a good-looking man, tall and kindly, who would always say, “Small prick coming.” It made me laugh every time.

I remember a block of rubber being placed in my mouth and the contact jelly rubbed into my temples. Then I was off. I never recalled anything of the shock itself and would come to in the recovery room shortly afterwards. There were so many patients being treated with ECT – it was like a conveyor belt. I must have had almost 50 ECTs in total during my entire stay. I count myself lucky, blessed even, to have a full complement of faculties today, in my mid-70s.

Only once was there a glimpse of the old me. My mother told me later that I had managed to manipulate her into bringing in my passport for some practical administrative reason. Somehow, I managed to get myself to New York and the Salvation Club for a private gig that Jimi Hendrix wanted me to attend. Once I had my passport, the rest was a breeze. A car was waiting for me outside the hospital, arranged by Jimi, and I was whisked off to Heathrow and on to a flight to New York. I arrived just in time to go to the club. I have little recollection of the gig or the rest of the night, but I do remember telling everyone that I was in a psychiatric hospital in London. I also took some drugs. Of all things, I took Tuinal, a sleeping pill. It’s what people took in clubs before Mandrax.

The next morning, I found myself on a plane bound for London. I dutifully rolled up to the Royal Waterloo and rang the bell. I’d become so institutionalised that I wanted to return to hospital. I suppose nobody believed where I’d been – they must have assumed I was delusional, like a lot of Sargant’s patients: “Been hanging out with Jimi Hendrix in New York, have you? Of course you have.”

My time in the Sleep Room left me hugely mentally incapacitated. I couldn’t make any decisions on my own. I needed help to choose what clothes to put on in the morning, what to order in a restaurant, and what to do with myself during the day. Most shockingly of all, I could no longer read. I recognised letters and words, but they made no sense to me, so I gave up. I watched television instead and sat with my parents like the dutiful lapdog they had always wanted me to be. I wasn’t happy or unhappy – I wasn’t there. It was as if my brain and personality were dead. I have no idea if my parents were satisfied with the new me, or whether they regretted Sargant’s brutal annihilation of my character.

Once, after my release, I had an outpatient appointment with Sargant at his private practice at 23 Harley Street. He was a huge man, tall, with an ugly mouth. My parents called him dapper. I asked him when I might read again, and he said he didn’t know. No one had had as much ECT as me, so he had no frame of reference. I found this horrifying, but not as much as what happened next – he actually came on to me. Tried to hug me and kiss me on the mouth. I wasn’t as docile as he expected and lashed out. I ducked and ran, hitting him sideways, and he went over on to an ottoman pouffe in the middle of the room. He was lying sprawled on the floor as I made my exit.

I sometimes wonder what I would say to Sargant if I saw him again. Probably what I said when I saw him on Bond Street a few years after he’d stopped treating me. He thought he was being very friendly and that I’d be thrilled to see him, but I called him a monster – to his face. I said it to the person walking past me, too.

“This man is a monster.”

And then I walked on.

2 months ago

61

2 months ago

61