As a toddler, Gerald Durrell was on a walk when he peered over the side of the road and spotted two creatures. “They were gently sliding over each other in what looked like a dance. They were a pale coffee colour with black, ridged stripes. They were glutinous and beautiful”.

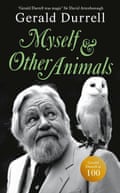

This rather flattering description of two slugs writhing in a ditch opens a new collection of writings by the beloved conservationist, who died in 1995 and would have turned 100 today, and it sets the tone for the book: all animals should be considered miraculous, conventional looks aside.

Myself and Other Animals – a riff on the title of My Family and Other Animals, Durrell’s 1956 account of his childhood on Corfu – traces the origins of the naturalist’s lifelong rapture with animals, combining his unfinished memoirs with extracts from his published books, articles, radio broadcasts, introductions to texts by other writers, and letters to his family.

The book “is an attempt to let Gerry’s life unfold for the reader, and for the reader to get to know him”, says his wife Lee, now honorary director of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, which was founded by Durrell in 1963 and has since helped more than 100 species recover from the brink of extinction.

Myself and Other Animals begins with Durrell’s unconventional childhood. He was born in Jamshedpur, India, but after his father’s death when he was three, the family relocated to England. His mother went to a nursing home after a breakdown, leaving Durrell with nanny-governess Miss Burroughs, who would lock him in various rooms including his bedroom at night, “as if I were a dangerous prisoner”. At school, he retaliated against a bully and was spanked; his mother immediately withdrew him. Lee suggests these early experiences might have been “why he was really a kind person, wouldn’t hurt a fly – literally”.

By 1935, the family were fed up with England and its weather, missing the warmth of India, so they left for Corfu. Arriving there felt like “being born for the first time”, writes Durrell. On the island, he became an autodidact, lying for hours observing the secret lives of animals and conducting dissections. There were dragonfly larvae which would “split open like strange sandwiches, and from their uncouth interiors would emerge the adults, hawk-eyed, wings glittering like a thousand church windows”. There were beetles, “rotund and neatly clad as business men, hurrying with portly efficiency about their night’s work”.

Sparkling descriptions of animal behaviour are the beating heart of Durrell’s accounts of trips to Cameroon, Guyana, New Zealand, Mauritius, Madagascar and elsewhere. Lee sees his “extraordinary” writing as part of his legacy, along with his more direct conservation work, including setting up Jersey Zoo and the Durrell Conservation Academy, which has trained more than 7,000 conservation practitioners. His books help “bring people closer to nature and develop a deep love” for it, “and therefore go out into the world, make the world a better place”.

after newsletter promotion

Towards the end of 1939, “when it looked as though war was inevitable”, the family returned from Corfu to England. Soon Durrell got his first job, as an assistant in a pet shop. Later he worked at Whipsnade Zoo, before he began a 10-year stint collecting animals for zoos on trips to Africa and South America, helped by an inheritance from his father.

Durrell’s concern for species extinction thrums throughout Myself and Other Animals. On the endangered aye-aye, he wrote that allowing such a creature to fall into oblivion is “as unthinkable as burning a Rembrandt, turning the Sistine Chapel into a disco, or pulling down the Acropolis to make way for a Hilton”. He considered human destruction of habitats to be “suicide”.

He lamented the difficulty of generating positive PR for animals that are in danger of extinction but do not have the “charming and decorative appearance” of animals like pandas. “It is awfully difficult to get people worked up over the fate of some obscure, drab and very probably ugly little creature however zoologically important it may be.” He reminded readers that animals can’t write to an MP or strike: “they have nobody to speak for them except us, the human beings who share the world with them but do not own it.”

Durrell’s descriptions of animals are often humanising – perhaps he saw that as the only way to make homo sapiens care. Brow-leaf toads suffer from “deep and ineradicable inferiority complexes”; a kangaroo about to give birth and thus cleaning her pouch by turning it inside-out is compared to a “rather frantic elderly lady” searching through her shopping basket for a lost train ticket.

Durrell also used his writing to criticise the widely held belief that zoos are “mere places of amusement” with little scientific value. He argued that at its best, a zoo could be a laboratory, educational establishment and conservation unit all in one.

What would the conservationist have made of the state of today’s world? Lee says he would be pretty upset. The Great Barrier Reef, which he explored and wrote about with awe, is now in “terrible shape” due to the climate crisis. “He’d have been absolutely sickened by it. But at least, through his eyes, we see this beautiful, amazing ecosystem as he saw it back in the 60s.”

3 months ago

62

3 months ago

62