I first met Robert Duvall in a muddy field in Maryland in 2001, on the set of Gods and Generals. It was a Warner Bros civil war epic, the kind of production where the scale alone made you feel small. I was playing a low-ranking Confederate aide-de-camp to General Stonewall Jackson. I was young, unsure of myself, and painfully aware of exactly where I stood in the hierarchy of things.

That morning, they placed him on the horse.

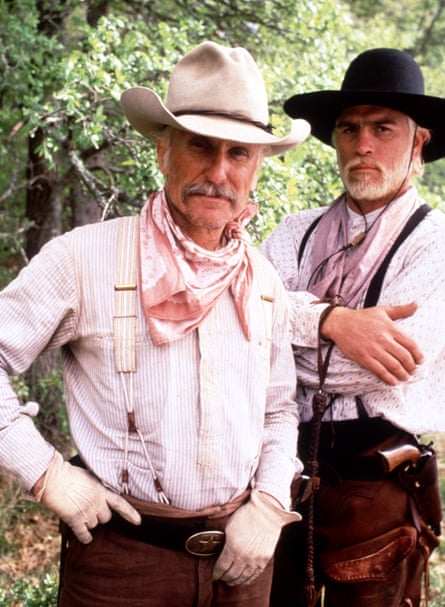

He sat tall and still in the saddle, dressed as Robert E Lee – grey coat, grey beard, grey sky above him – and he didn’t seem like an actor in costume. He seemed as if he had stepped out of the earth itself. He was Lee, and more than that, he was Duvall – a distant relative of Lee, too, which somehow made it all feel inevitable. He carried the weight of history effortlessly.

I remember standing there in my uniform, the wool damp and heavy on my shoulders, and feeling terrified. Not of him, but of disappointing the truth in the scene. He had a way of making you aware of truth without ever saying a word. We worked the entire day in that mud. Horses breathing. Cannons in the distance. Extras shifting in formation. And then it was over.

I retreated to my honey wagon – a sliver of a room somehow called a trailer. It was barely wide enough to turn around in, but to me it was a palace. I was just grateful to be there. I peeled off my boots, my socks damp and stiff, and began to change back into myself.

There was a knock at the door. I opened it to find Bobby’s assistant. He said, simply: “Mr Duvall would like to know if you’d join him for dinner.”

I tried to hide my shock. Duvall was legendary for calling out actors when they weren’t being truthful. He had no patience for falseness. He protected the work fiercely. The idea that he had noticed me at all was overwhelming.

Of course I said yes.

We met at a quiet restaurant not far from where we were staying. He was already seated when I arrived, relaxed, unassuming, almost invisible despite being one of the greatest actors alive. He looked at me for a moment and said, in that soft, unmistakable voice: “You’re a nice actor. You didn’t push the emotion.”

The scene was ultimately cut from the film. But that moment was not.

He didn’t elaborate. He didn’t need to. In those few words, he gave me something no one else ever had: permission. Permission to trust stillness. To trust restraint. To trust myself.

That dinner began a friendship that would shape the rest of my life. At the time, my acting career was unremarkable. I wasn’t getting the parts I wanted. I was drifting, quietly losing faith in the path I’d chosen. Bobby saw that before I ever said it aloud. He told me I should write. He had done it himself with The Apostle, released in 1997 and one of the most personal films ever made. He understood that sometimes you have to create the thing you’re meant to inhabit.

So I began writing. That screenplay became Crazy Heart. It was deeply influenced by his performance in Tender Mercies – that gentle, heartbreaking portrayal of a man worn down by his own life, searching for grace in the quiet corners. It remains one of the most truthful performances ever captured on film.

Bobby was the first person to read the script. He called me shortly after. “You’re going to direct it,” he said. Not a question. A statement. “I’ll produce it. Who do you want to play Bad Blake?”

I told him I had written it for Jeff Bridges, whom I didn’t know. And that I wanted T Bone Burnett to produce the music. I didn’t know him, either.

Bobby said, “Then write them letters.” Passionate letters. Honest letters. So I did.

A year later, Jeff finally read the script. The rest became part of my life’s story. But it began with Bobby’s belief. To call him a mentor is inadequate. He was as close to a father as I’ve ever known. He didn’t have children, and I think, in some quiet way, we found something in each other that filled a space in both of us.

We spoke nearly every day. Sometimes several times a day. We talked about Virginia – his beloved state, and mine. We talked about film endlessly. Coppola. Grosbard. Ford. Then Ray. Loach. Leigh. The Dardennes. International cinema we both loved, where truth was allowed to breathe.

One afternoon at his home in Virginia, he took me into his library – a quiet room filled with books, scripts, and the accumulated life of a man devoted entirely to the work. He led me to a corner where two handwritten notes were framed side by side on the wall.

One was from Gene Kelly, praising Bobby’s performance in Lonesome Dove. It ended with a gentle tease: “PS What, no tango?” Bobby smiled when I read it. Tango had become one of the great passions of his later life, something he shared with Luciana, his beloved Argentinian wife. He spoke about tango the way he spoke about acting – not as performance, but as truth. As listening.

The other note was from Marlon Brando. Brando praised Bobby as one of the greatest screen actors that ever lived, and ended with words that felt at once deeply personal and universal: “In the meantime, take care of yourself, direct another movie, and stop looking for Tangerine. She doesn’t exist.”

Bobby never explained what Brando meant. He didn’t have to. He wasn’t showing me those letters to impress me. He was sharing something quieter – a reminder that even the greatest artists carry doubt, longing and the lifelong search for truth.

That search defined him.

Regarding acting and directing actors, he would say: “Don’t rehearse your actors and never have a goal in mind. Start at zero and let the scene take you somewhere unexpected. If you’ve done your work, it will take you where you’re supposed to go.”

He believed that completely. He lived that way as an actor. You see it in The Godfather, in the quiet intelligence of Tom Hagen – consigliere to the Corleone crime family – the stillness behind the eyes. You see it in Apocalypse Now, in Kilgore’s terrifying calm. You see it in Tender Mercies, in every pause, every breath. And perhaps most of all, in his beloved Gus McCrae in Lonesome Dove. He never showed you emotion. He allowed you to discover it.

He never performed. He simply existed.

My wife, Jocelyne, and I were married on his Virginia estate, land viewed by George Washington himself in 1746. At that house and mine, we talked about everything. Sports. Politics. He was an old-school Republican. I was a liberal Democrat. But we listened to each other. Really listened. There was no performance in those conversations, either. Just curiosity. Respect. But it was film that bound us most deeply.

For more than two decades, Bobby was a steady presence in my life. He saw something in me before I had earned it. He protected that fragile early belief when it mattered most.

Years later, I had the privilege of directing him, alongside Christian Bale, in The Pale Blue Eye, in the winter of 2021-22. Watching him work again, after everything we had shared, felt like time folding in on itself. He was older, quieter, but the truth in him had only deepened. He needed less than ever. A glance. A breath. And everything was there.

Just recently, we had spoken about another role – a blind man in a story about a wounded civil war soldier making his way home through enemy territory, like Odysseus finding his way back to Ithaca. Bobby understood that man immediately. He knew his weariness. His dignity. His grace. It was a role he was meant to play. One we never got to make.

Robert Duvall’s legacy is secure. He is one of the greatest actors who ever lived. His work will endure as long as cinema itself endures. But that isn’t what I will miss most.

I will miss his voice on the phone.

His laughter.

The way he made me feel that the work mattered, and that I mattered, too. I will miss my friend.

I will miss Bobby D.

3 weeks ago

27

3 weeks ago

27