Almost three days into a South African government operation in which 78 bodies and 218 miners had been pulled out of an illegal goldmine, Zinzi Tom still had no news of her brother, Ayanda.

“I’m not coping, but I need to be strong. I need to put my feelings aside, I will deal with them after,” said Tom, 31, who has become a de-facto leader for relatives of the trapped miners. “I can’t lose hope. It’s something that I just can’t do.”

Police launched Operation Vala Umgodi (plug the hole) in late 2023 to try to stamp out illegal mining across South Africa’s north-eastern mining belt. Officers blocked supplies of food, water and medicine from workers underground in an attempt to force them to the surface so they could be arrested. But after miners started dying, authorities had to launch a rescue operation.

Analysts estimate there are 30,000 miners, known as zama zamas, producing 10% of the country’s gold.

“It’s an attack on our economy by foreign nationals in the main,” Gwede Mantashe, the mines minister, said in a press conference on Tuesday, adding that illegal mining had cost South Africa’s economy 60bn rand ($3.2bn/£2.6bn) last year.

In early November, police said their blockade of the mineshafts around Stilfontein had forced hundreds of miners to the surface since mid-October “as a result of starvation and dehydration”.

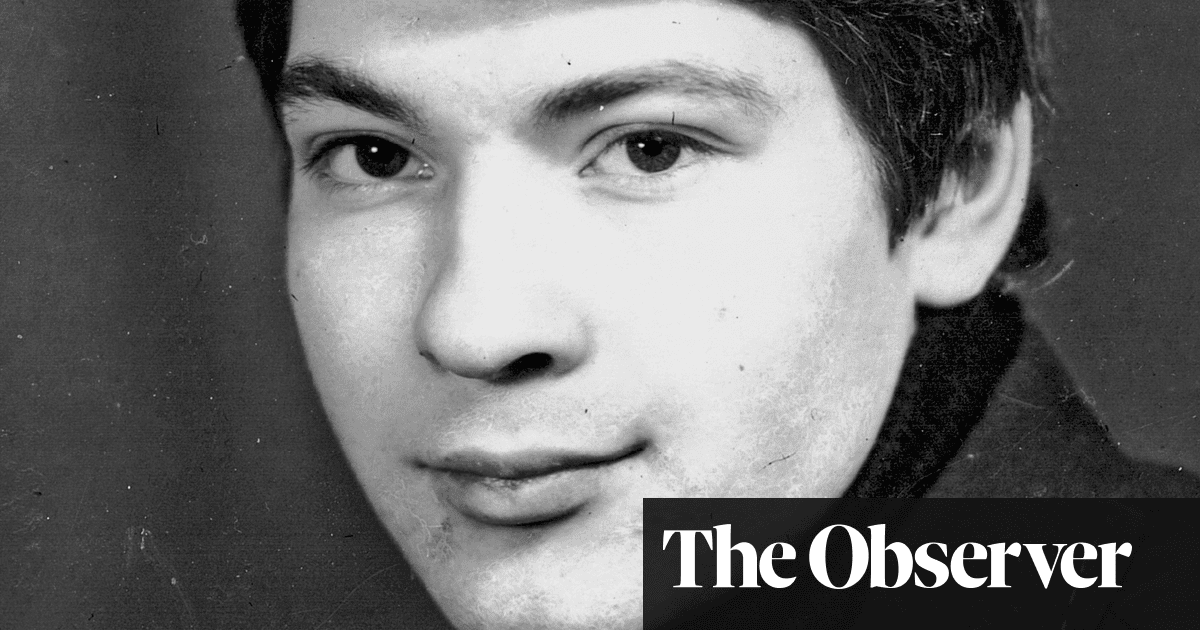

Later in November and December, they allowed some supplies to be sent down the 1.2-mile deep Buffelsfontein mine shaft about 100 miles south-west of Johannesburg, where Tom’s 26-year-old brother went underground in July, driven by hunger and desperation after being unable to find a job.

South African authorities have repeatedly claimed the miners are free to come out and that those still underground are trying to avoid arrest, pointing to more than 1,500 people who have resurfaced from another mineshaft in the area.

Activists and relatives argue that the two mines are not connected underground and that the food, water and medicine they have been allowed to occasionally send down the Buffelsfontein mine is not enough to stop people starving.

Speaking in Khuma, a township with a population of about 50,000 and home to many relatives of the illegal miners, Tom said people had been trying to bring miners out of the shaft with a hand-operated rope pulley system since November, when allowed to by police. But, she said, they had managed to bring out only 35 people alive, and nine bodies.

On 9 January, a letter brought to the surface said 109 people had died. Videos circulated by the NGO Mining Affected Communities United in Action (Macua) appeared to show more than 50 wrapped bodies underground and emaciated men begging to be rescued.

Tom then launched an urgent court case and the government agreed to the rescue, which is being carried out with a crane-winched cage operated by a private company.

Before the operation, Macua had claimed there were 400 to 800 people still alive in the mine. At the site on Wednesday morning, onlookers were kept on a road above the site, just able to make out bodies being carried away. Police guarded the entrance, frisking medical and forensic staff as they arrived.

In a single-storey brick house in Khuma, Angelila Moeletsi recalled the frustration and fear when she realised her 34-year-old son, Clement, had gone down the illegal mine on 24 July. She had thought he was staying with relatives in another province, looking for work as their family’s sole breadwinner.

Clement was pulled from the mine on 9 December and arrested. He was released on 30 December, but his mother had already developed a heart problem from the stress. “I am not happy with the way the government handled the situation,” she said. “Because people ended up losing their lives.”

3 months ago

72

3 months ago

72