The Korean wave is being feted around the world right now but Park Chan-wook is not feeling too celebratory. From the outside, South Korea seems to be a well-oiled machine pumping out a stream of world-conquering pop music, cuisine, cars, cinema (especially the Oscar-winning Parasite) and TV shows, as well as the Samsung flat-screens to watch them on. But Park’s latest film, No Other Choice, bursts the balloon somewhat. It paints modern-day Korea as an unstable landscape of industrial decline, downsizing, unemployment and male fragility – with no KPop Demon Hunters coming to save the day.

“I did not mean it for it to be a realistic portrayal of Korea in 2025,” says Park, a serene, almost professorial 62-year-old. “I think it’s more accurate to view it as a satire on capitalism.”

No Other Choice’s setting is the comically mundane but almost literally cut-throat world of paper manufacturing, where a freshly fired executive hatches a deranged scheme to get ahead by murdering his rivals for a new position, of which he does a pretty bad job. But it could just as well be about the entertainment industry, which is also more precarious than it looks, Park suggests: “Even though Korean films and shows are so globally trendy, Korean audiences have not been returning to the theatre after the pandemic, and there’s also talk around how the TV industry is being threatened. And this decline happened immediately after the success of Squid Game and Parasite. I think that gap in itself is very ironic.”

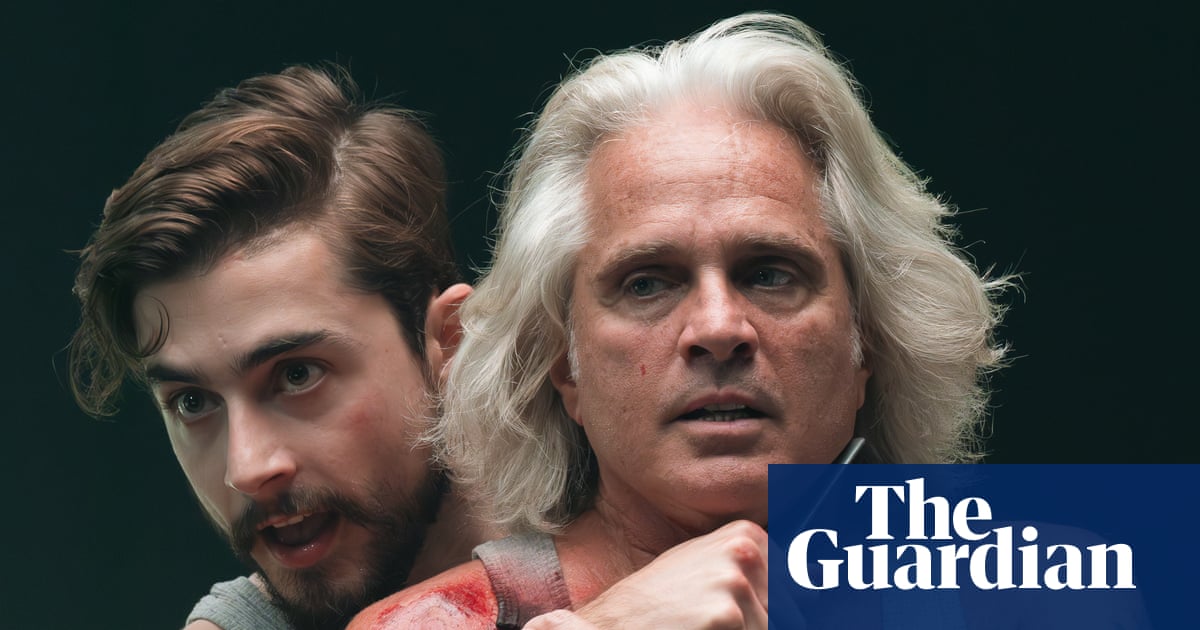

Irony is very much the mode with Park’s cinema. No Other Choice begins with salaryman Man-su (played by Lee Byung-hun) congratulating himself for having it all: a good job, beautiful house, loving wife, two children and two dogs. He welcomes the onset of fall, not realising it augurs his own fall: within days he is on his knees begging for work, having been made redundant by his new American bosses, which leads him to his deranged murder plan. It sounds bleak but it’s leavened by heavy doses of black comedy, mordant slapstick and clumsy violence, including a hare-brained plot to eliminate one of his competitors by getting obliteratingly drunk with him – via the very Korean technique of poktanju: a shot glass of whisky sunk into a pint of beer. Park was no stranger to this cocktail in the past, he admits, “but I don’t drink it any more. I realised that I shouldn’t be doing that to myself.”

Even No Other Choice’s title is ironic: Man-su clearly does have other choices. He could go after his employers rather than his peers. Or he could simply put up with being poorer – but he’ll do anything to avoid losing his house and his status, especially within the family. “The audience desperately wants to cheer him on and for him to find a job, but at other times, they realise that his choices are wrong,” says Park. “Those two feelings coexist, and the audience switches between them. That was the goal behind the making of this film.”

The greater irony here is that Park is practically the poster boy for Korean cultural clout. He has been on the crest of the Korean wave for the past 20 years, and alongside his compatriot, Parasite director Bong Joon-ho, he has broken down barriers for the country’s cinema. As with Bong, Park’s movies have combined festival acclaim with commercial appeal, not least his breakthrough Oldboy, which won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2004 and introduced the world to a new brand of vivid, gruesome, twisted but technically accomplished cinema – epitomised by the scenes where Oldboy’s protagonist dispatches multiple assailants in a one-take corridor battle, armed only with a hammer, and another where he eats a live octopus. In the UK, Park’s films were marketed under a DVD label called “Asia Extreme”, alongside works by compatriots such as Kim Jee-woon and Kim Ki-duk and certain Japanese directors.

Looking back, Park is uneasy: “I felt like I was getting boxed in because of that brand. It created an unnecessary form of prejudice.” He’s relieved that the label no longer applies, partly because his “extreme” aesthetic has infused mainstream cinema, but also because Park moved on with apparent ease to Hollywood and slightly less violent English-language projects. These included his 2018 John le Carré miniseries The Little Drummer Girl, starring Florence Pugh and Alexander Skarsgård, and 2024’s underrated The Sympathizer, about Viet-Cong spies in 70s America, featuring Robert Downey Jr in multiple roles.

“It’s not like I’m making intentional choices to mellow down my violence to avoid that sort of a reputation,” he says. “I don’t know what kind of films I’ll be making in the future, but they could be equally as graphic as my previous ones.”

Directing in English wasn’t as easy as it looked, he adds, especially on his first Hollywood feature, 2013’s Stoker, a Hitchcockian thriller starring Nicole Kidman and Matthew Goode. “I was scared at first, especially in regards to having conversations through an interpreter,” he says. He was helped by his actors. “It actually wasn’t that different, maybe because Nicole tried her best to adjust to me.” Kidman prefers to do her own preparation, he explains, whereas he prefers to sit down with the whole cast and work through the script line by line. “I suggested to her: why don’t we just try it out? And ultimately, she said it was very helpful.”

He is not fluent in English and is speaking through an interpreter today, but “my English is good enough where if I sense that something is not being translated correctly, I can point that out,” he says. “Another issue that could arise is misunderstanding from linguistic or cultural differences, but I’ve actually tried to use that to my advantage, because I could offer a perspective on British or American societies that people within the society might fail to see.”

Now, like Bong, he mixes it up: some projects in English, some in Korean, others a hybrid of the two. His sumptuous lesbian thriller The Handmaiden transposed Sarah Waters’ novel Fingersmith from Victorian England to early 20th-century Korea. Similarly, No Other Choice is adapted from The Ax, a novel by American crime writer Donald Westlake, but set in Ulsan, a coastal city in south-east Korea. Park has been trying to adapt the story since he first read it in about 2005, he explains – around the same time as a French-language adaptation of the same story was released. “Initially, this was intended as an American film in English, but lots of fruitless years have passed, and it eventually changed into a Korean film.”

The delay at least gave him the chance to cast Lee, who first worked with Park on his 2001 hit Joint Security Area, and more recently starred in Squid Game and voiced the chief demon in KPop Demon Hunters. Park describes him as “the Jack Lemmon of Korea” – handsome but expressive and versatile, a relatable everyman. “Before, he would have been too young for the role, but because a lot of time has passed, he had reached just the right age.”

Despite the story’s age, the themes of economic and masculine insecurity – and the victims of neoliberal capitalism turning on each other rather than the real villains – still resonate, especially in Korea. But Park has given it a very 21st-century update: the spectre of artificial intelligence looms large in this new industrial landscape, adding another level of irony to the tale. “While the original novel portrayed competition between humans, I added AI, which is so powerful that you can’t even compete with it any more,” he says.

Again, these anxieties are not limited to paper manufacturing – even if it can be seen as a metaphor for the dying age of analogue. Park is well aware that AI is coming for his own profession, too. “It doesn’t look as threatening right now, but considering the speed of its development in the past year, I’m very concerned for how many people in our film industry will have their jobs replaced by AI.” He’s worried for colleagues, he says, “but I’m also worried for a situation in which I have no choice but to embrace AI – for instance, if studios decide to cut budgets with AI.”

Either way, he’s unlikely to be bumping off his rivals, No Other Choice-style. Especially not Bong Joon-ho: the two of them are old friends. Park gave Bong his first job, in fact. “I asked him to work on a script for me, and we had discussions, but it never ended up happening.” The two have used the same actors, including Parasite star Song Kang-ho, and Park co-produced Bong’s 2013 sci-fi movie Snowpiercer. “Our wives are very close as well, so we meet up very often. And Song Kang-ho – his family is also very close with our families. So we often hang out together,” he says. “When I wrote the first draft for No Other Choice, I shared the script with [Bong] and asked for his feedback.”

Perhaps that’s part of the reason Korea’s screen culture has been so successful recently. Not only are they not at each other’s throats, their work often views economic success and the capitalist model with scepticism, if not downright pessimism. There’s no Korean equivalent of the American Dream, it seems. You could say No Other Choice tackles head-on the same ironies and inequalities as Bong’s Parasite, or his recent sci-fi comedy Mickey 17 – where a cloned Robert Pattinson plays the ultimate expendable worker. Or even Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Squid Game, with its life-or-death, winner-takes-all gameshow setup, which was inspired by Hwang’s own experiences of economic hardship after the 2008 financial crash. Perhaps Korean cinema is offering perspectives that we westerners are failing to see.

Not that Park has any stated agenda, philosophically, thematically or even geographically. As if to prove the point, he says his next two projects are both US-backed, but one is a sci-fi (adapted from the Japanese manga Genocidal Organ), the other a western (Brigands of Rattlecreek – it sounds very violent).

“If I got a proposal for a good story that takes place in France or in a country in Africa, I would go there,” he says. “I just follow good stories.”

1 month ago

27

1 month ago

27