“This man is my hero,” Michael Watson says simply as he turns to Peter Hamlyn, the neurosurgeon who saved his life and carried out seven operations on the stricken boxer’s brain in the aftermath of his fight against Chris Eubank in September 1991. “We are like family, me and Peter, and we have unusual banter. Peter says I’m a little bit dark to be family.”

Watson chuckles at his friend’s quip but, having interviewed Watson multiple times before and after the fateful bout that pushed him close to death, and having spent the morning with Hamlyn, I sense an essential truth. The brain surgeon and the boxer share a deeply compassionate intent to help each other.

Watson says: “The spirit between us has no colour. The power of love is real, isn’t it?”

Hamlyn replies gently: “That’s right, Michael.”

An hour earlier, while waiting for Watson and his carer to arrive, Hamlyn had spoken about the ways he had made boxing so much safer and how he had started the previously ignored discipline of sports medicine in Britain in 2005. But Watson dominates our conversation.

“Michael’s been an inspiring figure in my life and he was with me throughout a major tragedy in my family,” Hamlyn says. “We have three sons and five years ago our eldest boy died. Dominic was just 25 and he and his two brothers, Gabriel and Benedict, were wonderful guys and a real unit. They were called the blondies, because they’ve all got blond hair. I don’t know where they got that from.”

The flaxen-haired 67-year-old smiles despite the pain. “Dominic had just finished at Cambridge. He had helped his college win the rugby that year and he’d persuaded his rugby team to enter the rowing too. He was incredibly fit but he had something called SAD or sudden athlete death. Remember the footballer who collapsed [Fabrice Muamba while playing for Bolton against Spurs in 2012] and eventually got resuscitated? He was one of the few who actually came round. I was there when it happened to Dominic and, while I managed to resuscitate him, he died 24 hours later.”

The bond between Hamlyn and Watson, which had lasted almost 30 years by then, strengthened during the devastation of Dominic’s death. “Michael helped me so much,” Hamlyn says. “He was amazingly calm and very easy to talk to. He’d ring me most days to see how I was doing.”

Watson is again determined to help his friend as, on Wednesday, he walks a mile through London to raise money for i-Neuro, Hamlyn’s charity dedicated to researching brain illnesses and injuries. “Michael’s Mile” will be arduous for the 60-year-old as he struggles to walk. It offers a small echo of the epic feat Watson achieved when he completed the London Marathon in six days in 2003.

Hamlyn is the founder and president of i-Neuro, but he lingers over the link between his lost son and his old friend. “After school, Dominic joined us one afternoon during Michael’s 2003 marathon. Ricky Gervais also joined Michael and Dominic thought it was brilliant. Most disabled people are looked down on and talked to loudly and pityingly but Michael was a famous hero doing incredible stuff. That was one of Dominic’s great memories.”

Hamlyn pauses. “Around that time, Michael and I went to numerous schools where he talked about what had happened to him. He would get the students to feel the holes in his head from surgery. They’d come away knowing which side of your brain controls which side of your body. He talked about the fact that when he was rich and famous life wasn’t very good. He also explained why life is now rather better for him.”

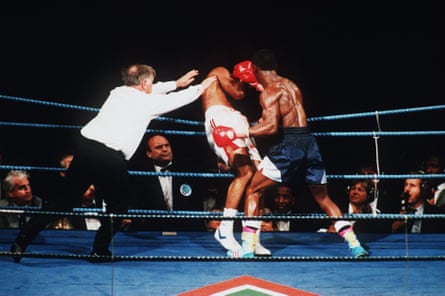

The surgeon first saw the boxer in the early hours of Sunday 22 September 1991. Watson had dominated his world title bout against Eubank at a seething White Hart Lane. He knocked down his bitter rival near the end of the 11th round and seemed to have won, only for Eubank to drag himself up and land a desperate punch.

That brutal uppercut caused catastrophe as a blood clot developed and exerted terrible pressure on the left side of Watson’s brain. He was let down by the British Boxing Board of Control, which failed to offer the necessary medical care at ringside or have an emergency plan in place.

It took almost two and a half hours for him to reach Hamlyn’s neurological unit and that delay changed the course of Watson’s life. The tragedy could have been averted because in 1989 Hamlyn had saved two boxers, Robert Darko and Rob Douglas, with identical injuries.

Both men recovered because, as Hamlyn says, “if a boxer is resuscitated properly, and kept oxygenated, given the right drugs, then you’ve got a good hour, maybe two, to get surgery”, adding: “Otherwise your brain is damaged every minute you’re not resuscitated. With Michael there was pandemonium in the ring. If you look at the pictures, his head is resting on a briefcase. That was the extent of his resuscitation.

“Eventually he gets to North Middlesex hospital, where he had the resuscitation now given as a matter of routine at ringside. But he was in the wrong hospital as they had no neurosurgeons. It was two and a half hours before I got knife to skin.” When Hamlyn sliced open Watson’s skull it was immediately evident “he was severely damaged – the only surprise has been the extent to which he’s recovered”.

Hamlyn had worked at Formula One races with Sid Watkins, his neurosurgical mentor who made grand prix racing so much safer. “When Sid started working in Formula One [in 1978] it was considered normal that drivers died. Sid changed that. He was driven by it and I guess I inherited that. Michael was the third boxer I’d seen with an identical injury and I thought: ‘This isn’t right, they’re not getting the care that F1 drivers get.’

“I heard this storm that boxing needs to be banned and I was thinking: ‘That’s not our job. Our job is to do the right medicine.’ Of course boxing is dangerous, but we need to take out the unnecessary harm.”

Watson spent 40 days in a coma and, in the midst of a self-righteous cacophony, the calmest voice belonged to Hamlyn. “I’d never been on TV,” he says, “but Des Lynam, a wonderful man, asked me: ‘What should be done?’ I thought: ‘That’s an easy question. You’ve got to do this, this, this, this.’ Years later Des said: ‘The remarkable thing was that you came out with this list of really obvious things.’”

Hamlyn reveals “there are 273 major A&E departments in Britain, and just 20 of them have on-site neuro”, adding: “So the likelihood of finding someone who can help you with an urgent brain injury is vanishingly small. For sports that threaten serious injury – motor sports, horse sports, combative sports – you need resuscitation on site and an evacuation plan. You need an ambulance and to know which hospital to head for in case of serious injury. The rest of my career was spent trying to disseminate that thinking across different sports.”

after newsletter promotion

The surgeon explains brain damage in boxing with piercing clarity. “If your head is against a wall it would be impossible to cause the injury Michael had. If your head doesn’t move, it doesn’t happen. The shearing force tears the blood vessels. If you’ve got an absolutely rigid neck, and know what’s happening, you’re very unlikely to get injured in that way. The big risk is being caught unawares and fatigued. So the main protection for a boxer remains the referee. They’re stepping in earlier and, of all the things done in boxing, that’s the most important.”

Boxing is so much better since Hamlyn’s recommendations were accepted. There have also been times when, while watching England play Test rugby, he has picked out four members of the side that have been operated on by him. But he stresses: “The creation of sports medicine as a speciality, which came out of our successful Olympic bid in 2005, was one of the greatest achievements. Until then there were no recognised sports doctors.

“As the medical adviser to the bid I told Seb Coe we had no sports doctors. I then explained this to Richard Caborn, the minister of sport, and he managed to get the Department of Health to agree to recognise sports medicine as a speciality if we won the bid. When we did, I stopped training neurosurgeons and started training sports doctors, as did lots of my colleagues from other specialities. By the time we got to the 2012 Games, it was run by sports doctors. It was a huge change and now Britain leads the world in sports medicine.”

Hamlyn is fascinated by new research in neuroscience using AI. He talks animatedly of innovations where “people who were paralysed are able to move artificial limbs just by thinking – they’re also training people who’ve lost their speech to drive an artificial voice box, again just by thinking”.

Watson’s brother Jeff sustained the same brain injury in a car accident when he was a boy. Meanwhile, Hamlyn’s brother Paul, an artist, has “occipital lobe dementia, which is the same as Alzheimer’s but the pathology starts in your occipital lobe and affects your vision”.

Hamlyn says: “Michael and I are fired up by what AI can do for neurological disorders. It analyses mobile phone data to diagnose neurodegenerative disorders that boxers and sports people get. Five to seven years before symptoms develop, we can identify changes by assessing the tone of your voice, your eye movements, how rapidly you dial the numbers, the extent of your vocabulary.”

The agony of walking a mile now awaits Watson. His left knee hyper‑extends and the quicker the pace the more it locks painfully. Hamlyn will walk every step with his friend: “I’m a worrier and I’ll be anxious until it’s done.”

Watson, whose nickname was The Force, oozes conviction: “I love the challenge and I’m a fighter. I’m the people’s champion so don’t ever quit on life. It has its downs but you can overcome them.”

I ask Watson about helping Hamlyn to withstand the loss of his son. “When I got injured I felt my spirit come out of this shell of my body. I flew to the heavens like a bird in the sky.” He turns to Hamlyn. “Dominic’s living now, in heaven, mate.”

We sit in the Rival Boxing Gym on the Caledonian Road, near Kings Cross and I ask Watson how he feels being back in a boxing space: “It’s home, a safe haven.” Watson is helped to pull on boxing gloves and, slowly, he hits the heavy bag. He shouts “feel the force” as he keeps punching.

He has to be persuaded to save himself for his long walk. Hamlyn says: “We have 50 runners running for i-Neuro and they will raise over £100,000. Frank Warren [the promoter] has donated £500 to each runner. That’s £25,000 on top, a stunning amount, from Frank. We can do an amazing amount of good with that.”

Watson leans forward to make me understand how much this matters. “Peter brought out the best in me,” he says. “I’m raring to go and so thank God for my hero. I love this man for saving my life and allowing me to look onwards and upwards.”

Walk a Mile with Michael on Wednesday 16 April at 1pm, from Wellington Arch to Horse Guards in London. Donate here.

2 months ago

42

2 months ago

42