When I ask Sean Scully what an abstract painting has over a figurative one it’s music he reaches for. “You might ask, what’s Miles Davis got over the Beatles? And the answer is: doesn’t have any words in it. And then you could say, what have the Beatles got over John Coltrane? Well, they’ve got words.”

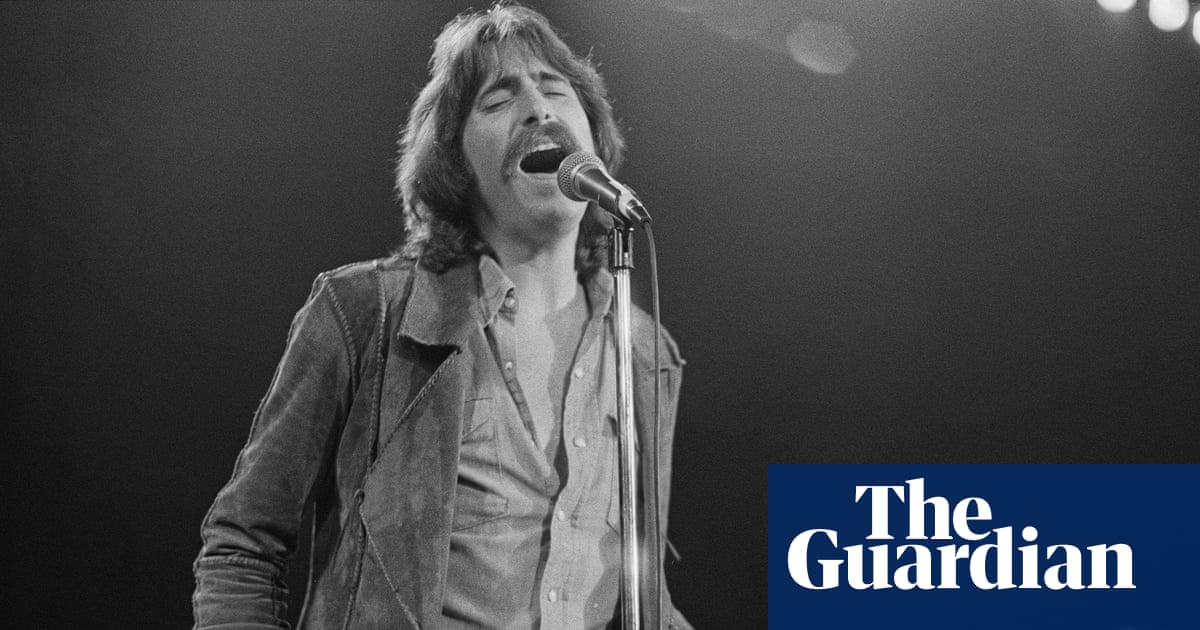

It’s clear which choice he has made. Scully, who paints rectangles and squares and strips of colour abutting and sliding into each other, is an instrumentalist in paint rather than a pop artist. The meaning of his art is something you feel, not something you can easily describe. He has more in common with Davis and Coltrane than with the Beatles. In addition to improvisational brilliance, his new paintings even colour-match with Coltrane’s classic album Blue Train and Davis’s Kind of Blue. For Scully, the greatest living abstract painter, is playing the blues in Paris. In his current exhibition at the city’s Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, long, textured blue notes as smoky as a sax at midnight alternate and mingle with black and red and brown in a slow, sad, beautiful music that doesn’t need words, art that doesn’t require images.

Those blues have been with Scully since childhood. “I got interested in blue because I had the blues.” He is still driven by pain, he tells me, over green tea in an upper room of the gallery. “Even now I’m terrified of the dark. I can’t walk across a room in the dark and I can’t get out of my car in the dark.” Luckily the gallery is brightly lit – all white. But the anguish is there in his art, a sense that under an apparently decorous, civilising order – patterns of rectangles as neat as ploughed fields or windows in a house front – bubbles up a storm of barely controlled feeling. In his Blue paintings that inner turbulence foams more mightily than ever.

Born in Dublin in 1945, Scully moved to London as a small child. He is named after his grandfather who hanged himself in military prison in 1916 in Chatham, Kent, while awaiting execution by firing squad – he had deserted from the British army to try to join the Easter Rising. But Scully doesn’t identify as purely Irish: rather he feels an internal tug-of-war. “I’m Anglo-Irish. And you’ve got this irresolvable, endlessly irresolvable dance between order and abandon that’s all in me all the time and it will be in me until the day I drop dead.”

He has been “tormented” since he was a child in postwar London. “I’m the product of a completely smashed-up family, an Irish family.” His father, too, deserted from the British army, during the second world war, and was imprisoned. By the late 1940s, “my mum and I were in this slum off the Old Kent Road. On my birth certificate for father’s profession it says ‘traveller’.”

His mother’s personality dominated his childhood. “My mother was really a hurricane. Or a monsoon, perhaps, would be a bit more accurate: she was warm and enveloping but left everything broken. So that would be a good metaphor.”

It was a conflict between his mother and the nuns who taught him that scarred him. She “got into a huge fight with them because they said if my father worked on a Sunday, the devil would move in under my bed”.

At the age of seven Scully was taken away from the scary nuns, but also from the ceremony and ritual beauty of Catholicism. “And so I had a kind of nervous breakdown. I went to the state school and I think that is when I became an artist. That incredible rupture. I asked my mother could I have an altar at home and she said no. So I lost my religion, and I’ve never been able to put it back together again. I’ve tried to put it back together with art.”

Scully trained in England as a figurative artist, supporting himself with manual jobs, then in 1975 moved to New York, where postwar art took a walk on the abstract side. When he arrived, the last abstract expressionists were battling it out with the minimalists. But for him the American avant garde had lost all feeling. “They got emptied out. They made art big and emblematic but also empty.”

Like who?

“Newman,” he says, referring to the abstract expressionist painter and sculptor Barnett Newman, who created fields of pure colour and vast space divided by vertical lines that have been interpreted as divine lightning: he vaunted the quasi-religious vocation of abstract art in his painting cycle Stations of the Cross. For Scully this was pure pomposity. He is even sceptical about that abstract expressionist holy of holies, the Rothko Chapel in Houston: “I found it extraordinarily underwhelming.” I bristle a bit because I love Rothko.

Despite his misgivings, Scully was and is an heir of these artists. He is attracted to the “religious, romantic” side of America that gave birth to their sublime art. In the 1970s and 80s, he found a way to infuse that romantic spirituality into paintings that at first glance looked like the regular, uninflected patterns and arrangements with which the minimalist movement sought to cool out their grand elders. He’s still moving shapes about with minimalist simplicity but with unmistakable inner passion. In his Blue paintings, he says, “I try to make abutments and unions and relationships that are difficult, strange, tender, poetic, that reflect all the ways that bodies can come together, that bodies can share something, just like we have to share this planet. I think about all this stuff when I’m making my paintings and that’s kind of what they stand for.” The scale of his paintings also matters hugely, or rather not hugely. “The fact that they’re so small I think makes them vulnerable in some way. And their intimacy is very, very strong. They’re not heroic.”

Clearly, he is still searching for the faith he lost as a child, and is deeply drawn to the spiritual dimension in art that made Rothko want to put his paintings in a chapel: “Abstract painting goes straight into your soul. So I think it has to believe in some kind of spiritual power. I mean, that’s its function, because it’s pre-verbal, isn’t it? It goes bang, straight inside.”

As he speaks I can see his paintings downstairs, rivulets and ridges of blue and black and tear-pools of paint that do speak directly to the soul. But I wonder whether it’s the “English” side of his Anglo-Irish identity that has enabled him to renew abstract art. His paintings have a meat-and-potatoes English empiricism, a digging down into real feelings.

And Scully really has been shattered. In 1983 his first son, Paul, died in a car accident aged 18. “Those things, they just feed on themselves.” He “went off the rails” with grief. “I have a lot of sadness in me, but I love painting. I love it. I’m so happy in my studio. I go there every day. I love to go there and mess around or prepare something, you know, do something. But when I paint, I paint very, very direct.”

He has flown to Paris today from Dublin where he has just opened a show and has another coming up in London. Scully is devoted to family life and dotes on his teenage son Oisin. Not long ago they moved to London for the schools. Now they’re back in New York because Oisin “detested” London. And they’re attending a Catholic church, because even though Scully cannot recover his faith, his son has become interested in religion. In his garden, he has a replica of the bridge from Monet’s garden and beyond it statues of Buddha and an angel. He likes to tease visitors by saying: “You can’t speak loudly because there’s an angel,” as if he believes there’s a real one out there.

Abstract painting is still divisive: random squares, dollops of colour are all very well but aren’t they just pretty patterns like wallpaper? Today, a lot of what passes for abstract art is as vacant as dots on wrapping paper. But truly powerful abstract painting, like Scully’s, has a sense of necessity and inevitability: it must be this way. It expresses mysteries that can’t be put in any other form.

In spite of his scepticism about Mark Rothko’s chapel, Scully is the only abstract painter around today I would dream of comparing to the Russia-born, Jewish American genius. In the Blue paintings you sense a Rothko-esque mystery and intensity.

“When you listen to Nessun Dorma,” he says, again reaching for music as an analogy, “it makes you cry – but you don’t know what the words are. That’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to break people’s hearts. I want to make abstraction popular without lowering the bar.”

1 month ago

25

1 month ago

25