If you want to contemplate quite how far back Status Quo’s roots go, consider this: the band’s founders came together before the Beatles had released their first single, before the idea of “the band” was even a thing in pop music. They’re often dismissed as one-song wonders, or as proponents of brutally simplistic music – but as much as the Stones or the Who, Status Quo are carved into British rock.

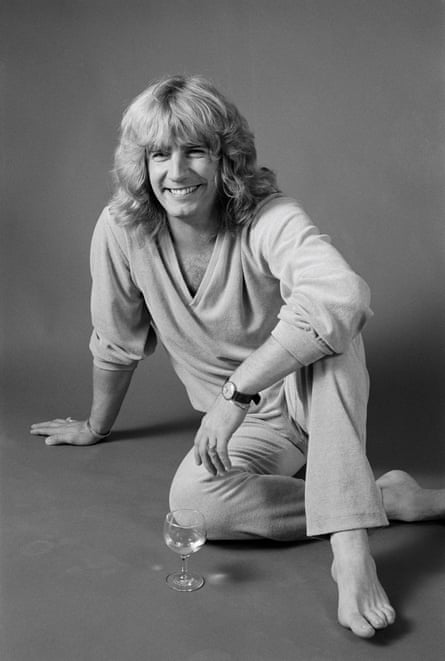

Francis Rossi and Alan Lancaster formed the Spectres in 1962, when the guitarist and bassist were still at school. Drummer John Coghlan signed up a year later and Rick Parfitt completed the “Frantic Four” when he joined after sharing a bill with the Spectres at Minehead Butlin’s in 1966. The Beatles showed Rossi not just what he could do with his life, but touched something very primal in him.

“Everybody liked them,” he says, “and I must have been a wimpy kid, and I terribly wanted to be liked. Still do in some ways. That’s quite sad. But we tried to emulate them – that’s where we wanted to go.” Over 60 years on, he’s not there yet, despite the end of his iconic partnership with Parfitt, who died aged 68, in 2016. “I don’t know what else to do. I’m obsessed by it all, and I just keep going.”

Rossi, everyone says, doesn’t like talking about the past. He doesn’t have much choice today, because we’re talking as Quo prepare to reissue the 1977 album Live!, recorded in Glasgow when the band were at their peak as a rock band: when their force and power was as blunt and brutal as the Stooges, but without the nihilism, and with added massive hit albums and singles.

The first was in 1968, with the ersatz psychedelia of Pictures of Matchstick Men. “We weren’t very happy being dressed-up pop stars. And our tour manager, Bob Young, said, ‘Well, why don’t you change?’ So we grew our hair long, got rid of the clothes and put on jeans and T-shirts. And boogie was the right music to play.”

For Rossi, the boogie style – the tough, hard rock version of the 12-bar blues, exemplified by songs such as Whatever You Want or Roll Over Lay Down – also tied in with the shuffling Italian music he grew up with in south London. “There are so many things in our lives that are shuffles, even nursery rhymes – Nellie the Elephant. Our marches do that. It appealed to me and it still does.” That was crossed with what he was hearing on the university circuit Quo were playing. “We used to work with Fleetwood Mac a lot on the uni circuit,” Rossi says. “You could sit down beside the stage and they’d start playing – der-der, der-der – for an hour and a half. We wanted to do that, to be that.”

Quo were constantly written off as “heads down, no-nonsense, mindless boogie”, Rossi says, and were parodied as such by Alberto y Lost Trios Paranoias on a 1978 single. But there’s more to them than that. Their 1975 No 1 Down Down, with its multiple sections, is like the Paranoid Android of 12-bar boogie, or consider that What You’re Proposing was one of two consecutive Top 20 hits – along with Living on an Island – about cocaine-addicted alienation. The latter, written by Parfitt, was speaking plainly about waiting for people to come to Jersey with drugs for him. The former, by Rossi, was more allusive but its theme was evident. “I used to believe what I read in the press, that there was nothing to the lyrics,” Rossi says. “But then I’d read them and think, ‘That was about my first wife, that was about such and such.’ In doing it, I think it’s far too” – he pulls a face to suggest a highfalutin intellectual – “to say, ‘I’m going to write about this now.”

But the truth will out, nonetheless. “That’s what I think, yes.”

The new reissue of the live album – the full sets from all three nights at the Glasgow Apollo in October 1976 – could really have been recorded anywhere and at any point during the mid-70s. For a start, their set didn’t change a whole lot through those years: “We had a good set and we stuck to it,” drummer Coghlan says. “And it meant I didn’t have to look at a set list.” And, second, Quo worked so hard through those years that they were like a juggernaut, night after night. “They weren’t afraid of hard work, and they got their heads down,” says Bob Young, their tour manager. “We were just one of those bands that liked playing,” Coghlan says, plainly.

One of the curiosities of Quo is that its members almost always co-wrote, and they didn’t look far for co-writers. Young has his name on a bunch of Quo’s biggest hits, which must have made him the highest-earning tour manager in rock history. Young laughs at the thought, though accepts it was probably true: “I ended up in the unique position of being tour manager, songwriter and harmonica player.”

But, as time went on, the writing with others reflected the fact they weren’t getting along with each other. “It got to a point where we should have taken some time off, maybe three or four months,” Coghlan says. But they didn’t. Coghlan left in 1982, kicking over his drum kit during a recording session and walking out without a word, sick of his bandmates. Lancaster, who had formed the band with Rossi, departed after the End of the Road tour in 1984. And Parfitt was haunted by insecurities about his status within the band – specifically about having always been viewed as No 2 in the group to Rossi, who stood centre stage and took most of the vocals.

“He was my greatest friend, but someone” – Rossi can’t say who – “got to him. Somebody knew it was a weakness with him. And as we got older it got worse and worse. I always saw it as the two of us, because we made a great pair – and I think we were a bit unfair on the rest of them. We would sit in the car and hold hands and dress the same just to wind people up, and I think certain people decided to get between the two of us.”

Rossi, plainly, is an unusual person. “Francis has always been his own man,” Young says. “He’ll say what he wants; he hasn’t got a lot of filter, like it or not.” In his autobiography, Rossi mentions his tendency to say inappropriate things and cause offence, and says he doesn’t visibly grieve the deaths of those he has loved, including Parfitt. I mention to him that those were both traits of mine, that I obsessed over until being diagnosed as neurodivergent and learning they were common behaviours: a lack of grief is related to object impermanence about people. Has he, I ask as delicately as I can, ever been tested?

He looks not horrified but fascinated. “You’re the first person that’s ever broached that at all. And now there are loads of things going on in my mind, because that would explain …” He starts to talk about the deaths of his mother and father, how he poked at his mother’s body to be sure she was gone, how when he was told his father had died he just wanted to check on the arrangements for his own perfectly normal working day: “I said, ‘Is the car coming to pick me up?’ And it makes me feel like I’m cold. But if I’m in a situation and I’m told what I’m supposed to do, I can’t do it. I’m supposed to grieve, I’m supposed to say certain things. And I will be thinking, ‘I shouldn’t say that, that’s not appropriate.’ It’s interesting, what you said. I never thought about that before.”

Rossi, 76 in May, isn’t going to give up anytime soon. He outlines his plans for the next couple of years, talking about how he still loves playing to an audience. And he says something else, something familiar from my parents’ generation of working-class people who grew up to be comfortable, but aware of their past. “The thing that worries me constantly is: will I have enough money if I stop now and there’s no more income? I’m scared shitless of that.”

Of course Francis Rossi is not going to die in penury, but it’s a comment that shows he’s a more complex man than the jeans and waistcoats and winks to camera ever hinted at. Just as Status Quo were a more complex group than anyone who claimed they only had one song could ever understand.

3 months ago

135

3 months ago

135