Just before the graphic artist Rebecca Burke left Seattle to travel to Vancouver, Canada, on 26 February, she posted an image of a rough comic to Instagram. “One part of travelling that I love is seeing glimpses of other lives,” read the bubble in the first panel, above sketches of cosy homes: crossword puzzle books, house plants, a lit candle, a steaming kettle on a gas stove. Burke had seen plenty of glimpses of other lives over the six weeks she had been backpacking in the US. She had been travelling on her own, staying on homestays free of charge in exchange for doing household chores, drawing as she went. For Burke, 28, it was absolute freedom.

Within hours of posting that drawing, Burke got to see a much darker side of life in America, and far more than a glimpse. When she tried to cross into Canada, Canadian border officials told her that her living arrangements meant she should be travelling on a work visa, not a tourist one. They sent her back to the US, where American officials classed her as an illegal alien. She was shackled and transported to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) detention centre, where she was locked up for 19 days – even though she had money to pay for a flight home, and was desperate to leave the US.

Burke had arrived in the US during the Biden administration, only to become one of 32,809 people to be arrested by Ice during the first 50 days of Donald Trump’s presidency. Since February, several young foreign nationals have been incarcerated in Ice detention centres for seemingly little reason and held for weeks, including Germans Lucas Sielaff, Fabian Schmidt and Jessica Brösche. (Brösche, 26, spent more than a month in detention, including eight days in solitary confinement.) Unlike these other cases, Burke had been trying to leave the US, rather than enter it, when she was detained for nearly three weeks.

I had been following news of Burke’s trip since she arrived in the US on 7 January. To me and my family, Burke is Becky, our neighbour and, for two and a half years, the person who took care of my kids after school. Her London home was only five doors down from us, but we met online, through a website that matches families with people offering childcare. Becky spent her mornings as a graphic artist and comic-book editor, and her afternoons collecting my son and daughter from primary school and entertaining them back at my place, making them snacks and refereeing their squabbles. Best of all, she drew with them. When my daughter turned seven, she asked if she could have a comic-making party; all her friends went home with little zines Becky had helped them make. We felt so lucky to have her in our lives.

Two years ago, Becky went to San Francisco for two weeks on a Workaway placement, staying in a family home free of charge in exchange for sweeping floors and walking the dog. Last August, she used Workaway again, in Switzerland. The internet was opening up the possibility of another life for her – one where she could see the world on a shoestring. In September, Becky told me she was going to leave London in January to go travelling on her own. We were sad to see her go, but I was full of admiration for her; I wish I had been as bold and free in my 20s. We threw her a farewell party just before Christmas; everyone cried. I kept up with news of her travels on Instagram, and there were regular postcards and WhatsApps: pictures of the tattoo she had got in Portland; a video she filmed of herself on a forest walk. She told me she had seen bald eagles and woodpeckers, deer and seals. And then, on 26 February, everything went silent.

Becky wasn’t someone who liked to be immersed in global news. But, even if she had been, she could never have foreseen what would happen to her. She booked her plane ticket six months ago, while pundits were still predicting a close race for the presidency, or a Kamala Harris victory. Her story gives a glimpse of what America has become since then.

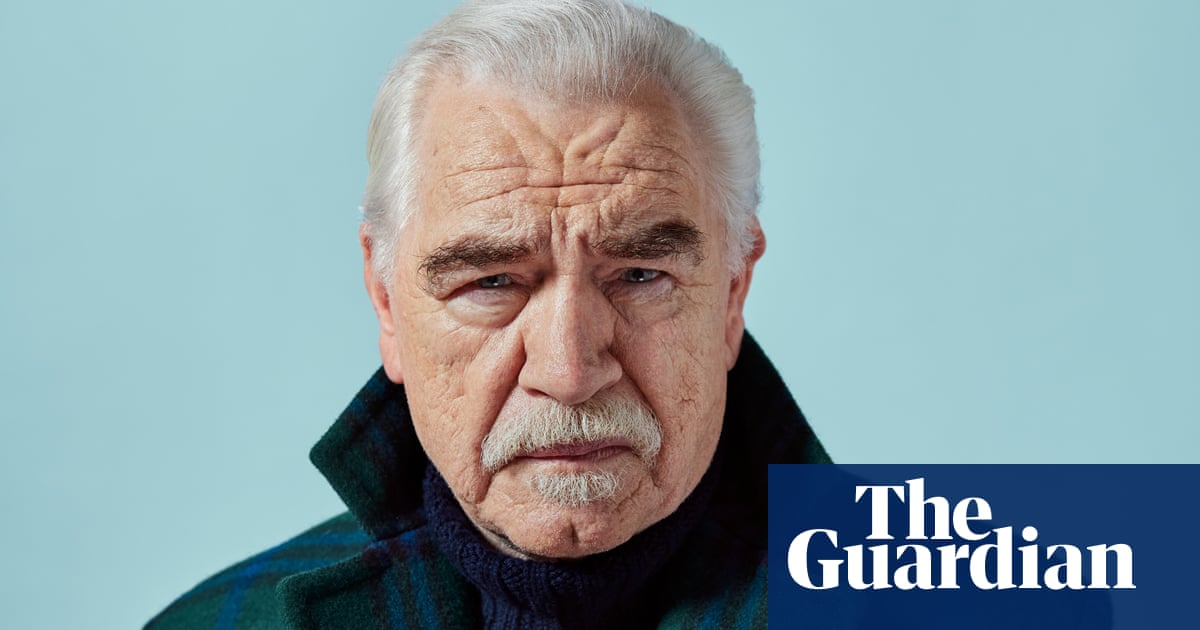

I meet up with Becky at her parents’ house, in Monmouthshire, six days after she arrived back in the UK. After so long in detention, she wants to spend as much as possible in the sunshine, so we sit in the garden while their dog – a cocker spaniel named Mr Bojangles – runs circles around us. Becky is much paler than the person my family knew so well. Her eyes are hollower.

She began her trip with a stopover in Iceland, taking in the northern lights, going on to spend three nights in a hostel in New York City. Having already stayed in San Francisco on a Workaway placement, she didn’t feel she had anything to hide when she landed in New York. She would have told the border official her plans in full had he asked about them, she tells me. But he didn’t.

The homestays were a big part of the appeal of her trip. “I really liked becoming part of these other families. You don’t get placed so firmly in the community if you’re going to a hotel that’s sterile and separate.” Her first placement was three weeks with a household just outside Portland. Becky would “destroy dandelions from their lawn” and cook meals; her hosts took her on day trips, including an overnight stay at the seaside. They drove her to her next homestay, which was in Portland itself. Becky’s second host took her on forest hikes. “She knew every single plant, every single bird call. It was like having a personal tour guide,” Becky beams. “It was incredible. I thought, this is going too well, I’m having too much fun here.”

Both her hosts had been worried about how the US was changing under Trump. “I’m hearing so many scary stories about Ice raids and passports being detained,” Becky WhatsApp’d me on 8 February. Her first host had a transgender friend whose passport had been seized after she tried to change the name on it. But Becky felt like a spectator to it all. “I was worried on their behalf – an abstract worry and concern for others – rather than for myself. Because, I thought, I’m getting out of here.”

On 26 February, Becky boarded a Greyhound coach for the three-hour ride from Seattle to Vancouver. She was due to spend two months in the home of a divorced father who wanted help with meal prep and laundry during the one week out of every two that his kids lived with him. Becky had never been to Canada before and was looking forward to this part of her trip. She sat at the back of the coach, listening to a comedy podcast, watching the world flash by.

She wasn’t thinking about the dismal state of US-Canada relations when she handed her passport to the Canadian border official. He asked what she was planning to do in Canada. Travel, she replied. He asked where she was staying. Living with a man and his family, she said. He asked how she knew him. Becky said they had met on Workaway, and that she would be helping out around the house. The official told her they needed to research what Workaway was. He told Becky’s coach driver to leave without her.

Workaway warns users that they “will need the correct visa for any country that you visit”, and that it is the user’s responsibility to get one, but it doesn’t stipulate what the correct visa is for the kind of arrangements it facilitates in any given country. Becky had always travelled with a tourist visa in the past – including to the US in 2022 – without any problems. She checked that work visas were only required for paid work in Canada. She had had months to plan her trip, and would have applied for a work visa if it was necessary, she says.

But the Canadian officials told Becky they’d determined she needed a work visa. She could apply for one from the US and come back, they said. Two officers escorted her to the American side of the border. They talked to the US officials. Becky doesn’t know what was said.

After six hours of waiting – and watching dozens of people being refused entry to the US and made to return to Canada – Becky began to feel frightened. Then she was called into an interrogation room, and questioned about what she had been doing during her seven weeks in the US. Had she been paid? Was there a contract? Would she have lost her accommodation if she could no longer provide services? Becky answered no to everything. She was a tourist, she said.

An hour later, Becky was handed a transcript of her interview to sign. She was alone, with no legal advice. “It was really long, loads of pages.” As she flicked through it, she saw the officer had summarised everything she told him about what she had been doing in the US as just “work in exchange for accommodation”. “I remember thinking, I should ask him to edit that.” But the official was impatient and irritable, she says, and she was exhausted and dizzy – she hadn’t eaten all day. “I just thought, if I sign this, I’ll be free. And I didn’t want to stay there any longer.” So she signed.

Then she was told she had violated her tourist visa by working in the US. They took her fingerprints, seized her phone and bags, cut the laces off her trainers, frisked her, and put her in a cell. “I heard the door lock, and I instantly threw up.”

At 11pm, Becky was allowed to call her family. Her father asked what was going to happen next. “I looked at the officer and he said, ‘We’re going to take you to a facility where you’ll wait for your flight. You’ll be there one or two days – just while we get you on the next flight home.’”

Becky was shackled and put into the back of a van. “I had no idea where we were going. It was just bumping around in darkness with handcuffs on.” At 2.30am, she arrived at the Ice facility in Tacoma, Washington. She was made to change into standard-issue underwear, a yellow top and trousers. Officers took away all her personal belongings, measured her height and weight, made her pose for a mugshot, and assigned her an “A” number (short for “alien”). Whenever she asked the people processing her arrival how long she would be detained for, they told her they couldn’t help: they worked for GEO, the private company contracted to run the facility, and not Ice, the government body that would decide her fate.

At 5.30am, she was taken to the dorm that she was to share with 103 other women: a massive room filled with metal tables, benches and bunk beds, some cells around the perimeter, and a row of payphones, “like a hospital mixed with a canteen”. It was bathed in bright halogen light that Becky would come to learn would always be on, albeit slightly dimmed between 11.30pm and 5.30am. Becky’s bunk was on a mezzanine level.

All Becky wanted to do was sleep, but instead she headed to the payphones to make the one free call she had been told she was entitled to, to tell her family how to put money into her inmate account. “In my head, this was a thing I had to do immediately, otherwise I’d be stuck without a way to communicate with the outside world.” She gave her parents her A number, and they tried to reassure her. It’s just one or two days, they repeated to her. A horrible experience. But over soon.

As soon as the call ended, Becky went on one of the detention centre iPads, which had apps allowing inmates to send messages to Ice and check the balance on their inmate account. “I sent a message to Ice straight away saying: ‘I am a tourist. I was just backpacking. I have not outstayed my visa. I’ve only been in America one month and two weeks. I don’t know why I’m here. I want to go home. Please can you help?’” She frantically refreshed the app to see if her account had been credited. (It took longer than expected, because funds can only be transferred into accounts for “illegal aliens” from within the US. Becky’s father, Paul, discovered he could only do it through an American friend.) “I was seeing no money arrive, and I was getting really upset thinking I told them the wrong A number.”

As she sobbed holding the iPad, Becky found herself surrounded by other inmates who wanted to comfort her. A woman called Lucy offered to let Becky use her phone credit if money hadn’t appeared in the account within a few hours. Rosa, a Mexican woman who spoke barely any English and had already been detained for 11 months, offered Becky a Pot Noodle she had been able to buy from the commissary, the shop where they could purchase luxuries. At 8am, Becky finally curled up in her bed to sleep, with Rosa praying in Spanish in the bunk below.

after newsletter promotion

Becky quickly learned the monotonous rhythms of the detention centre. Wake-up time was 5.30am. Breakfast – which for Becky was cold potato and a sachet of peanut butter, the only vegan option – was at 6am. Lunch – black beans and more cold potato – was anytime between 11.30am and 2pm. Four times a day, inmates had to sit on their bunks for an hour so they could be counted by staff. Dinner frequently arrived after 8pm. They were often ravenous between meals, which was why the commissary was so vital. It was also the only place they could access shampoo, deodorant, nail clippers and anti-shank toothbrushes.

On her first day in the facility, Becky asked for a scrap of paper and a pen, and began to draw the inmates on the table next to her. She was immediately inundated with portrait requests. A Mexican woman called Lopez, who had a photo of her children stored on one of the iPads, told Becky she would buy her some paper and colouring pencils from the commissary if Becky drew her kids. She soon became the dorm’s unofficial artist-in-residence, with women huddling around the dirty mirrors to make themselves look presentable before they sat for her. They would decorate their cells with Becky’s drawings, or send them to their families. Lopez declared herself Becky’s manager. “She kept saying, ‘Becky, you need to ask for stuff in exchange. Ask for popcorn.’ And I’d be like, ‘Lopez, I don’t need anything.’ I thought, I’m here briefly, you’re stuck here a long time. I’m not going to take your food away from you.”

The majority of the women were from Latin American countries, but some were from India, China, Iran, Afghanistan and Gaza. “Most of them were asylum seekers, but there was this handful of new people who had come in recently who did not know why they were here.” Lewelyn joined the dorm a few days after Becky. She had just returned from visiting her family in the Philippines; she had been living in the US since 1976, working as a lab technician at the University of Washington hospital’s cancer centre. “She’d had a visa issue that had been resolved many years ago, but now it was flagging on the system again.” Kseniia, a Russian woman who had been working for two years in a California nail salon, had permission to work in the US but was handcuffed while waiting for her husband to come out of an Ice interview. “She was so confused. She kept saying to me, ‘I’ve got a work permit.’”

There were other tourists, too. Bana, from Romania, was on holiday in Canada and visited Peace Arch park, on the international boundary between the US and Canada. She told Becky she had been taking selfies with her husband when a US border official told her they had strayed into American territory without the right visa and took her into custody.

Becky had arrived in the detention centre on a Thursday. She soon realised she would not be out of it before the end of the weekend. No one ever replied to the message she sent to Ice on the iPad; she found out the Ice officer assigned to her case had gone on annual leave. The following Monday, Paul contacted the Foreign Office in London, and the British consulate in San Francisco. “They were doing the diplomatic bit,” he tells me. “But, after seven days, I could see it wasn’t really working. My perception is the British consulate couldn’t get Ice people to respond to them. There was no end in sight.”

After Becky had been incarcerated for more than 10 days, Paul decided to go to the media. A quiet, unassuming man, he found himself live on Newsnight, Sky News and Good Morning Britain. Becky made it to every national newspaper in the UK, and had coverage in US press, too. Hours after her story broke, she was visited by an Ice officer who told her she was now “at the top of the pile” to be processed. Four days later, on a Thursday, another Ice officer came to the facility to tell Becky her flight had been booked for the following Monday.

Becky’s face began to appear in the newspapers they received at the facility. At one point, her face flashed up on one of the three TV screens they had in her dorm. “Everyone clapped. After that, a few people came up to me and said, ‘Can you put me on TV, too?’” She feels very guilty that she was able to leave. “I was aware that it was from a major position of privilege that the press listened to this story. I was a British tourist, I had these images of my trip on Instagram, and I had contacts with journalists, so I was very lucky. And I wanted the same thing that Ice wanted, which was for me to go home.”

At lunchtime on 17 March, officers came into the dorm, barked Becky’s name and told her to get ready to go. She had hidden some of her drawings among her official paperwork – her signed transcript and the document declaring her an illegal alien – in the hope she could smuggle them out. She wasn’t allowed to tell her family she was on her way home, but one of the women offered to ring her parents to notify them. Becky was shackled at the ankles, wrists and waist, and then made to shuffle out into a van.

“When I got close to the airport, I felt really relieved and also overwhelmed, watching people with their suitcases, people going on holiday. It was a bit like whiplash – reality whiplash. Did that just happen?”

But her ordeal was not over. She was taken to the basement of Seattle-Tacoma international airport for a security check. While every item in her bag was swabbed and dismantled, she was subjected to a full body search. “I was in this very loud, weird, industrial space with pipes and conveyor belts and lights and sirens, being told to open my legs. I was silently crying, watching all my stuff being torn apart as someone else was searching every crevice of me.” She boarded the plane before any of the other passengers. “I found my seat, threw my bags on it, and went into the toilet and sobbed in the cubicle, with the British Airways classical music surrounding me.”

Six days after she landed at Heathrow, Becky still sleeps with her lamp on. She is enjoying home-cooked food and long showers, but feels guilty for resting in comfort when she knows her friends are still incarcerated. “I’m thinking of them every day,” she tells me. She is working on a comic that will tell the story of what happened to her, and the women she shared 19 days with, based on the drawings, notes and official documents she managed to take out of the detention centre.

Becky still doesn’t know why she was incarcerated for so long. She suspects it might be because Ice is simply overwhelmed. “Maybe border security have been pressured to prove they’re stepping up.” She shrugs. “It did feel like they wanted to get me from the moment I was walked to the American side.” On 4 March, the White House issued a statement celebrating how “Ice arrests of illegal immigrants have surged 627%” during Trump’s first month in office.

Jasmine Mooney, a Canadian woman who was detained by Ice for two weeks, says while the private companies who own the facilities are run for profit, there’s no incentive to get people out quickly. But in the era of Elon Musk’s department of government efficiency (Doge), it seems counterintuitive for public money to be deliberately wasted on detaining illegal aliens with the will and means to return home.

Trump’s border tsar, Tom Homan, promised “shock and awe” from day one of his administration. Perhaps Becky’s incarceration was political theatre – or performative cruelty. Whatever the reason, in Trump’s America, a tourist who makes a mistake can be locked up, seemingly indefinitely.

The deportation paper Becky signed bans her from the US for the next 10 years. Paul tells me they are going to try to appeal it, but Becky says America isn’t the country she thought it was. Her advice to anyone planning to travel to the US is simply not to go. “First, because of the danger of what could happen to you. And, secondly, do you really want to give your money to this country right now?”

She has emerged from the experience with new eyes. “I was naive to think that what was going on in the world, or at the border, wouldn’t affect me,” she tells me, her arms folded across her chest. She had believed if she was honest and acted in good faith she would be insulated from harm, but now thinks that might have been naive, too. “If I’d lied, I’d be on holiday in Canada right now.”

14 hours ago

3

14 hours ago

3