The day after I turned nine, 27 August 1961, I conquered the bicycle. After weeks of wobbly, failed attempts while on vacation at my older cousin Lillian’s house in Michigan, I had finally done it! I got on that bike and away I went. I turned a corner without falling and rode back to the porch, where my friends whooped and hollered in celebration.

The cheers faded suddenly. Everyone stared at me. Lillian, zombie-eyed with her mouth open, held a shotgun pointed downwards. Somehow, I hadn’t heard it.

My skinny body contorted. My blue floral shorts set with tiny ties at the shoulders was now crimson.

“Lillian, you shot me!” I yelled. “Call the police!”

The blast of Lillian’s shotgun, intended for her husband, shredded my right kidney, appendix and large intestines. A suction pressed on my back as the blood gushed to the floor; the smell of iron overwhelmed. That shot caused permanent tendon and nerve damage, intestinal devastation and temporary paralysis.

Each shooting tragedy in the US takes me back to that porch. In recent years, I am back in that place far too often. In 2024, 250 children were killed – and 40,850 deaths due to gun violence were counted, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

In the ambulance that August day, I asked the paramedic: “Am I going to die?”

“I can’t promise you anything,” he replied.

His hopeless response would end up traumatizing me more than the actual gunshot.

Fight or flight? I chose to fight. There was no oxygen or pressure applied to stop the bleeding. I repeated my phone number in my head over and over. In the emergency room, I whispered: “Call my Mama – Henderson 1-3631,” and passed out.

A visiting trauma surgeon stopped the bleeding and repaired, rerouted, repurposed, or removed multiple organs. Years into the future, doctors would marvel at his artistry. But at the time, the prognosis was bleak. I had lost a lot of blood. If my reconstructed intestinal system worked, if I did not have diabetes, if I survived the surgeries, I would never walk, or have children. If I survived at all, that is.

After a month and a half of going in and out of comas, I awakened to my mother, Helen, rejoicing at the sound of my passing gas. My bowels were working. Standing at my bedside for all those weeks, her feet were swollen like loaves of golden-brown bread.

On my first day home, my mom sent back the hospital’s wheelchair and declared: “Edie, to get back to school, you’re gonna need to walk, baby.”

She had watched me in physical therapy and knew my potential. The pace was set; I would not be bound. I was to have a normal childhood, even if I looked far from normal. I wore a metal, polio-style brace on my right leg attached to my black-and-white lace-up Oxfords. I hobbled with the help of pine wood crutches.

But my own father, Charlie, a former prize fighter and baseball catcher for the Negro Leagues, was enraged. Eventually, he let go of the torture of his fury and accepted the blessing of my survival. He returned to his original belief system: hate kills.

As a part of my morning routine, my mother hid the colostomy bag taped to an open bowel on my right side. With these new “private parts”, a safe secret, I went off to school, Campfire Girls, and every activity I chose. In the evenings, I had chores and cared for my baby brother. Even though I was a spectacle to behold, I would function at my maximum ability, and I did.

I gained the unexpected gift of resilience and later, empathy, which I draw upon daily as a therapist.

Back in the 1960s, psychotherapy just wasn’t a reality in my community. Black folks, both then and now, are often in a survival mode that requires emotions to be compartmentalized. People prayed and cried it out. Most talked to elders.

Now in my fourth decade of practice, I see therapy as an absolute necessity for healing after a shooting. My advice to childhood victims and their parents: initiate therapy as soon as possible. That pain is too raw to manage alone. There, parents can openly cry about their losses, allowing themselves to become angry. Kids may want to drop in and out of therapy when bored; they need to be allowed to be fluid with going in and out of counseling. Also, buy a punching bag.

Find low- to no-cost artistic expression opportunities for kids – cheap because they are going to dump most of them. When they show interest without encouragement from you, invest a tiny bit more. Let them discover their authentic passion. They will cherish and practice it when they cannot talk to anyone. Whatever it is, when they drop it, you drop it. On to their next adventure.

A goal for all survivors is to identify the trauma and related triggers and deal with them, experience them, and manage their context and their symptoms. I did this with the help of no-talk therapy, often used with children who have had lives that were unspeakably hard. The therapist creates a space, provides toys, art supplies for creativity and is silently present as the child speaks through his choice of creations and movements. I use play therapies with adults.

My own no-talk therapy continues. I dress dolls, crochet hats, write poems, and make crazy dog outfits for crazy Brooklyn dogs. My husband is treated to an all-out mini musical nearly every day. The healing power of artistic expression is immeasurable. My parents allowed me a giant toolbox, and I was taught to pray, sing or crochet when I needed to soothe myself. Making someone happy with a small gift I made still carries a childlike anticipation.

PTSD is for life. Sixty years after I was shot, in trauma therapy due to a car accident, I recalled the burning metal, gunpowder smell from the shotgun blast (the deployed airbags used a similar chemical). Still, if you are dealing with the aftermath of a shooting, there is hope. With family, community and therapeutic support, one can learn to manage their emotional pain.

In my practice, I transmit that belief to others as I did with Carmen, a 15-year-old Latina girl with a history of neglect and abuse who became a thief. She went on to complete high school and become a buyer at a store she once stole from. Or, Belinda, a 10-year-old Caribbean girl who was a burn victim. She stopped speaking for months. Via no-talk therapy, we alchemized her survival instincts into strength. She became an actor at school and began thriving in all areas of her life.

In times of inexplicable tragedy, we can also turn to our elders. I believe that seniors, an often neglected asset in every community, having lived through wars, recessions, pandemics and more, can play a healing role in post-shooting scenarios. Tap into the mentorship programs such as the Adopt a Grandparent program. Young and elderly people can mutually benefit in exchanges of old and new experiences. No such program in your community? Sister with a team and develop one.

I benefited from two Black elders – my mother Helen, and my mentor, Robin – into my mid-60s. They taught me that the anger and resentment that I could have carried all these years would have caused me to lose faith in people and disengage.

We all have something to offer. We should take inspiration from the enslaved African American’s obligation when illegally learning to read: “Each One Teach One.” If you are 18 and have witnessed violence, you can mentor a 13-year-old victim who feels that this life is no longer worth living.

I first walked without my brace and crutches at 14 because I wanted to enter the Cleveland Forest City Scholarship Pageant. I have since ridden camels in Egypt, flown on hang gliders in Virginia and ziplined in Alabama, all unimaginable in the weeks after the shooting.

As I write these words, the metal pellets from that shotgun blast remain dotted around my spinal column – paralysis was a possibility if they were removed. I guard my mental health as much as my physical. My spirit depends on how well I manage them both. My resilience bears out in my work in helping others as a therapist and the fact that I still ride the bicycle, a triumph, one of many, from that day of the shooting.

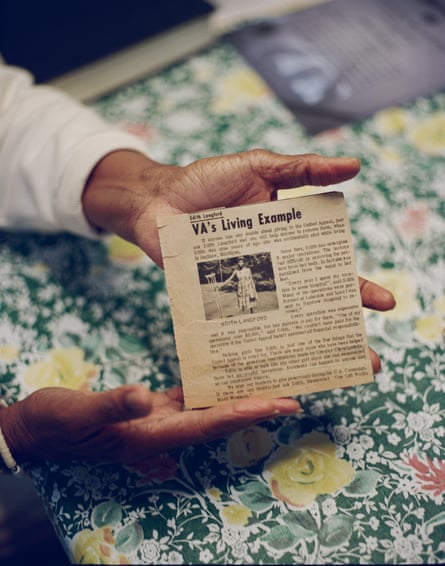

Edith Langford, PhD, 72, is a therapist, occasional adjunct professor and is currently working on a memoir of trauma and thriving and recently published an opinion piece on problem gambling among seniors

3 months ago

102

3 months ago

102