A convoy of bikes and cars cruises through the streets of Davao City, decked out in the campaign colours of former president Rodrigo Duterte and his family. Green balloons and red ribbons bop and flutter in the breeze. Cars beep their horns and passersby stop to raise their fists in support of the former leader.

The motorcade is as noisy and colourful as any election campaign event in the Philippines, which will vote in midterm polls on Monday. But this procession is different. Duterte, who is running as mayor of Davao, his family’s stronghold, is imprisoned thousands of miles away in The Hague, following his arrest in March for the crime against humanity of murder over his deadly so-called “war on drugs”.

Between 12,000 and 30,000 civilians were killed in connection with the crackdown from July 2016, when Duterte took office as president, and March 2019, when the Philippines’ withdrawal from the international criminal court (ICC) took effect, according to estimates cited by the ICC. Most of the victims were young men in deprived urban areas, who were shot dead in the streets.

As his supporters’ motorcade snakes its way through the evening traffic, a song blasts out: “Bring back Duterte to the Philippines … “Filipino will judge, and not a foreigner.”

Duterte’s arrest has been celebrated by international human rights groups and by victims of the merciless crackdowns, but in Davao, where Duterte was mayor for more than 20 years cumulatively before he became president, it has evoked defiance and sympathy for him.

“He was mayor here in Davao since I was born,” says Ney Cabatuan, 41, who joined the procession on his motorbike. “He’s really very strict. But we thought of him as a father, and we are his daughters and sons.” The former leader’s tough policies were for the good of the city, he adds, and stamped out crime and unrest.

“We’re praying and we’re begging that he [will] really come back.”

Many supporters question the evidence provided to the ICC, and say Duterte should be tried in local courts, or argue the killings were necessary.

“They say that he is a bad man, but actually for us, for Filipinos, especially for Davaoeño, he is a hero,” says 39-year-old nurse Marilou Caligonan, who is among those who stop to raise their fist in support of Duterte as his supporters’ motorcade passes.

“That war on drugs is very good for us … Actually if you want to have a good country … you kill just a small part of people or a small number of people for the sake of millions. That’s what he’s doing,” she says, adding that the streets were far safer and that there were fewer drug users in the community.

Supporters argue the killings that occurred were legitimate because they took place during police operations, and that victims had fought back against the police – a defence often given by the authorities that has been disputed by rights groups.

Duterte, 80, is expected to win the mayoral race, though it is likely, given his absence, the role would instead be assumed by the vice mayor, a position being contested by his youngest son, Sebastian.

The Duterte family faces a less certain picture elsewhere in the country, however, where elections are playing out amid a vicious power struggle between the Dutertes and the family of the ruling president Ferdinand Marcos Jr, with the former fighting for their survival.

The Dutertes face legal problems that extend beyond the ICC case. Duterte’s eldest daughter, vice-president Sara Duterte, was impeached in February on a range of accusations including a plot to assassinate the president and claims of corruption. She will soon face a trial in the senate, and, if she is to avoid a guilty verdict, needs as many allies as possible to gain seats on Monday. If the senate convicts her, she will be barred from running for the presidency in 2028. This would leave the Dutertes, once seen as an untouchable political force, without a successor.

In a speech at a rally in Manila on Thursday, Sara Duterte said her name, and her family’s name “have been dragged through the mud”. “Who will really benefit if the Duterte family is gone from this world? Not the Filipinos, not the victims of crime, the unemployed, the poor or even the hungry.”

In Davao, midterm campaigns have been led by Duterte’s children and grandchildren, four of whom are running for office, as

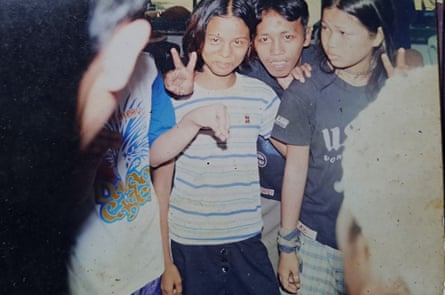

Small teams of volunteers guard the former president’s house day and night, saying they do not trust the authorities to follow due process. Cardboard cutouts of the former leader stands outside the gate, for visitors to pose for photos. On his 80th birthday last month, tens of thousands gathered in the city, sharing birthday cake, and singing.

‘Governance by fear’

Born into a political family, Duterte was elected mayor of Davao in 1988 following uprisings that ousted the late dictator, and father of current president, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. As mayor, Duterte presided over the transformation of Davao, a city then gripped by crime and militancy, but which became known as one of the safest places in the country.

His merciless crusades against crime in Davao came at a huge cost, however.

Clarita Alia’s four sons, Richard, 17, Christopher, 16, Bobby, 14, and Fernando, 15, were killed under the crackdowns, between 2001 and 2007.

Alia, 71, said she was so afraid for her children at that time, she could not sleep. “I told my children, I said ‘don’t go outside. What if something happens to you? They will take you.’”

Her children were accused of involvement in crime. Police told her they were on a “kill list”, she says. They were stabbed to death. No one was held accountable for their murders.

Other families in Davao are too scared to speak up, Alia says, but she had done so because she wanted to stand up for the victims of the killings, “and for those who could still become victims if no one stops them”.

In a senate hearing last year, Duterte, who became president in 2016, said he kept a “death squad” of criminals to kill other criminals while serving as a mayor. He added that he offered “no apologies, no excuses” for his presidency. After his arrest in March he said in a video message that he would take responsibility for his policies.

Mag Maglana, an NGO worker who is running against Duterte’s son Paolo for a congressional seat, describes Duterte’s leadership as “governance by fear”. A belief had been instilled in people that “a strong police presence, strong military presence, strong leaders, a culture of not resisting” was needed to protect the city from drugs and instability, she says.

“I think that has affected our ability to think for ourselves about the kind of leaders that the city deserves,” says Maglana, who adds that she is running to show local people they do have choices. Anti-drug campaigns had targeted the small distributors who are often poorest, she said. “The big players, they’re obviously still here.”

How far the views of Rodrigo Duterte’s supporters are shared by other Filipinos will help shape Monday’s vote, and decide the future of the Duterte family. In Davao, supporters say they will vote in their defence, and to protect the vice-president from her impeachment trial. “This is our revenge,” says Cabatuan.

1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31