They arrived in 80s London with small intentions: to study, to work, to outrun what they had come from, and then maybe, one day, return back home. A people who came en masse from Nigeria, working the dark hours, balancing two jobs with part-time education, rolling in a ceaseless loop of morning shifts into lectures into night work again, until maybe a qualification came good, and they could move into some kind of steady career or profession.

Many of us grew up with these stories, parents who worked quiet jobs for decades, who cleaned offices in the glass Canary Wharf skyscrapers before first light and then, in the summer evenings, waited on tables at Soho and Knightsbridge restaurants. Aunts and uncles and elders who earned their first wages in London at local bowling alleys and bingo halls, at cinemas and hospitals and care homes, moving anonymously through a looming city.

My father worked in restaurants, and studied at a local polytechnic, living in Southwark and then in Lewisham, part of a sprawling network of Nigerian people slowly spreading through the city. They built close communities for survival, found home in one another, settled into foreign surroundings, attempting to make this place their home. By the early millennium an estimated 90,000 Nigerian-born people had arrived in the UK, and yet, despite this mass migration, they remained on the margins, rarely present in the national story.

This is a story about football and belonging in the soul of the city, but to tell it, I must start with conflict. Our stories in the diaspora begin far from London. History remembers the years 1967 to 1970 as the Nigerian civil war, the Biafran war, a brutal fight for freedom, a struggle to remain whole. The war has its origins in the terrors of the colonial period. There is no us without the violence that birthed Nigeria, without the scars of empire mapped on her skin. In the 17th century, the British first arrived in the region. Slowly, they bled the land of its fruits and came to bathe in its gold. By the early 1900s the empire had carved lines into west African earth, reaching from the coastal plains and rainforests in the south and sprawling inwards, to the Sahel savannahs in the north. Four hundred ethnic groups with their own languages, their own cultures, their own sense of identity, now fused into one. Britain titled this new, giant state the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria.

Their union was uneasy. In 1960, when independence from Britain was declared, the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria was voided and Nigeria was born anew. But the tensions between varying ethnic groups remained. History remembers those civil war years as genocide: an estimated 3 million people killed, half of them children. Death by gunfire, by blade, by starvation. Some fled to Britain as refugees. Some remained, for a time, resigned to waiting out the bloodshed.

You are not the same after war. Its demons live with you, in memory, in mass graves, in the knowledge that your country can suddenly crumble and good men can turn into murderers. Against the backdrop of further conflict and political instability, people continued to leave for London, a great migration peaking in the 80s when the price of global petroleum crashed and Nigeria’s economy collapsed, and the oil-rich nation was brought to its knees. My father and his people were among those who left. We in the diaspora were yoked from these colonial conflicts, among the country’s children and grandchildren living in the jaws of the same terror who bore her.

Nigeria’s growing presence in London can be traced by the moving tides of Britain’s national sport. Since its inception, the Premier League has reflected the social movements in the capital’s furthest corners. London is a mirror, its people and communities a reflection of Britain’s relationship with the world, an echo of its colonial history, its bonds with Europe, built and then fractured, its reputation as a home for global finance and for refugees seeking asylum. When Nigeria’s war generation emerged into the world, their arrival in English football was inevitable.

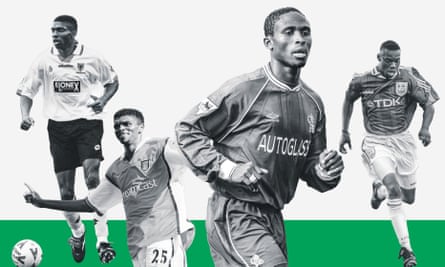

In November 1992, a 17-year-old George Ndah, born in Camberwell to Nigerian parents, and turning out for Crystal Palace, walked on to the pitch at Anfield. It was the Premier League’s first season, just three months after the competition had started. That afternoon Ndah claimed the title of Crystal Palace’s youngest ever Premier League player. Ndah was not alone. Efan Ekoku, born in Manchester, also to Nigerian parents, was present in that first season, playing for Norwich, before eventually moving south to London to play for Wimbledon, where he stayed for five seasons. Both he and Ndah would receive call-ups for the Nigerian national team. They were British-Nigerians with split ties, emblems of a new London entering the world.

The 1994 squad that won the African Cup of Nations was Nigeria’s golden generation. They emerged at a time of continued political instability and violence. In June 1993, a military coup had overthrown the interim government and Nigeria returned to rule by dictator. It was the country’s eighth coup, or attempted coup, in three decades, its second in four years.

Under Dutch manager Clemens Westerhof, a clutch of young footballers were picked to form a squad that continues to define the country’s footballing image, both for those living on home soil and for those raised in London. After claiming African Cup of Nations gold in Tunisia, the squad – defined by the likes of Jay-Jay Okocha and Rashidi Yekini, Sunday Oliseh and Stephen Keshi – qualified for the 1994 World Cup in the US, and went as far as the last 16. Two years later, at the 1996 Olympics, they claimed victories over Brazil in the semi-final and Argentina in the final.

In the wake of this international success, many of the golden generation’s core members followed the trail of their brothers and sisters to London. From those squads spanning 1994 to 1998, Olympic team captain Nwankwo Kanu signed for Arsenal from Inter Milan in 1999, Celestine Babayaro for Chelsea in 1997. Others signed for clubs outside London: Jay-Jay Okocha for Bolton in 2002, Finidi George for Ipswich in 2001, Taribo West for Derby in 2000, Daniel Amokachi for Everton in 1994.

For many English fans following these clubs week to week, these players were brief footnotes in a long history. But for those who had arrived in London from Nigeria, these footballers were fellow countrymen in a far continent, their first glimpse of themselves on the stages of mainstream British culture.

I was around two years old when that golden generation came of age, too young to watch the fantasy play out in real time. But we inherited these stories, tender moments handed from father to son, vague accounts of an uncle’s friends’ classmate who had played with Kanu back home, or a squad player who shared our ethnicity. They were reflections of who, and of what, we came from. Football and footballers define our childhoods in that way. They are a small but constant presence in our formative years, central to the week-by-week routines that flower into rituals, anchoring us to the land. In this gradual forming of a person, footballers become cornerstones of our early lives, markers of how we remember ourselves and the particular time period our generation emerged from.

My childhood has a thread of these memories, small moments and traditions on which I built my early sense of self. A huddle of uncles and family friends fanned out across living rooms in Lewisham and Peckham council flats, watching Kanu in FA Cup finals and Premier League games, their collected frustration with English pundits mispronouncing his name during the commentary, the same way teachers mispronounced our names in school. One afternoon my dad was driving out by the Thames in west London and saw Kanu coasting along in his car. I remember my father banging his horn, extending a wave, and I remember Kanu beeping back, returning a nod. A moment of recognition for two countrymen in a crowded city.

There was the afternoon we were parked outside Stamford Bridge, waiting for an uncle who worked in the ground as a security guard, an afternoon so vague that sometimes I question whether it happened at all. The only thing that remains concrete was an understanding that my uncle worked in the same club where Babayaro played his football, and from that, a feeling that we existed as one – a loose network of Nigerians threaded throughout the region.

And this is how I remember those early years, our ties to our origins maintained by phone calls and letters sent to Nigeria, landing with rarely seen uncles and aunts and an ageing grandmother. By our elders who etched themselves on to the city’s canvas, recreating home in the traditions they had brought with them. In the monthly community meetings in family front rooms and Elephant and Castle community centres, at the many christenings and holy communions in churches across the city, at the summer gatherings and hall parties in Bermondsey that went on past dawn. In the dishes we shared at dinner and the language my elders spoke. In the music poured through the home at family gatherings and the politics they discussed when the night called for something more serious.

I knew Nigerians living in all corners of this place. They had passed down a sense that there was no separation between us and what was happening thousands of miles away, that we were more “that” than anything here. The rest of England was an afterthought, a land that existed somewhere beyond the community cradles we had been raised in.

Our relationship to national identity is a deeply personal one, a container for conversations about heritage and community, politics and acceptance. In these intimate reckonings, football often sits at the centre of the stories we have been told and continue to tell ourselves.

I can chart my own boyhood feelings of home and belonging through this prism. My earliest interactions with international football are not defined by the celebrations laced into the collective memory of wider England. I feel little connection to defining moments such as David Beckham’s free kick against Greece to qualify England for the 2002 World Cup. Or Paul Gascoigne’s goal at Wembley v Scotland in 1996, and his near miss in the semi-final that followed, both moments I discovered decades after they had happened. I was absent for the famed 5-1 defeat of Germany in Munich and have no memories at all of England playing at Euro 2000.

We lived in an alternate world. The Super Eagles were our countrymen, a team whose stories and legend we had been raised on. The first international football shirt I remember owning was a Nigerian fake my cousin had brought with her from Lagos. My name was misspelled on the back.

This sense of separation would surface in encounters out in the wider world. There was the 2002 World Cup in Japan and South Korea, where Nigeria was drawn against England in the final game of Group F. They played on an early Friday morning. Our primary school screened the game in the assembly hall. Lessons were cancelled. The students and teachers gathered around a raised TV. When the match began, my brother and I cheered for the players in light green, the only two people in the hall to do so.

Elsewhere, I remember the long bank holiday weekend in 2004 at Charlton’s football ground, the Valley, in Greenwich, for the Unity Cup, where Nigeria played Ireland and Jamaica. The tournament was created as a celebration of the three countries said to be among the largest diasporas in London. And we sat in the away end with my father and my uncles and their children and thousands of other Nigerians. We waved the country’s flags from the stands, grew impassioned whenever we touched the ball, or won a corner, or crossed the halfway line. We watched our team win both games, emerging out of the friendly tournament as champions. It was my first experience of live international football. That was Nigeria as I had known and experienced her, my childhood defined by a country I had never set foot in.

By the early years of the new millennium, the Nigerian community had existed in London and Britain for nearly decades. But a presence in the England national team had remained fleeting. John Salako, who spent most of his career in south London playing for Crystal Palace and Charlton, turned out for England in 1991, gaining five caps. There was the late Ugo Ehiogu from Hackney, who played four friendlies between 1996 and 2002, and Wimbledon striker John Fashanu, who played against Chile and Scotland in 1989. After retiring, Fashanu would say: “The fact is that I really wanted to play for Nigeria and I came home on three occasions, but the coach said I was not good enough to make his team, and so never selected me except for one friendly match against China where I was an unused substitute … it pained me so much that I never played for my country.”

Some of those born or raised in London continued to turn out for Nigeria. There was Danny Shittu, born in Lagos and raised in the East End. Brothers Efe and Sam Sodje, born in south London, their family originally from Warri in Nigeria’s Delta state, both turned out for Nigeria too. Their younger brother Akpo, a forward, never made the step up to international level, but remarked once in an interview: “My dream is to be my country’s No 1 striker.”

By the time I came of age, the glory years of Nigeria’s golden generation had long faded. Nigeria failed to qualify for the 2006 World Cup, and there were group stage exits in 2002 and 2010. The African Cup of Nations brought a solitary win in 2013, and failures to qualify in 2012 and 2015. John Obi Mikel, the golden boy of Nigerian football, who promised to return a sense of flair and creativity to a flailing national team, joined Chelsea in 2006. During his time in west London, he was transformed by José Mourinho into a mechanical, ruthlessly efficient defensive midfielder. The tease of what could be, the frustrations at what was lost, stung all who watched.

Nigeria’s 2023 African Cup of Nations team included five British-Nigerians. Alex Iwobi, nephew to Jay-Jay Okocha, was raised in Newham, east London, as was defender Calvin Bassey. Ademola Lookman, Ola Aina and Semi Ajayi are all from the south of the city. They are a new generation, joining a long tradition of London-raised Nigerians opting for green and white. Collectively they have been termed the “innit innit boys”, an affectionate nod to their British accents. Iwobi, speaking in an interview about the decision to play for Nigeria said: “I always felt at home in England but more connected to the west African nation.”

This group of players was key to the team’s run to the tournament’s final, Nigeria’s first in a decade. The team reflected Nigeria and her children as they exist in the present day: families spread across continents, frayed by the aftershocks of colonialism and war and political turbulence and economic turmoil, reuniting briefly under the banners of the Super Eagles. In the national team, they find themselves again. For 90 minutes, Nigeria is whole.

Some of that first generation who came to Britain have returned to Nigeria, driven away by conflicts of racism, isolation or the call of home. Many have stayed and built lives in London. My own father returned to his homeland. Many of his friends remained.

The children, born or raised here, have grown affectionate for the place we have learned to call home. In London as the years passed, we have celebrated births and birthdays and buried those lost. Some have started new families, bringing a second generation of British-Nigerians into the world. We worked our first jobs and found our first loves here, built a continued sense of kinship and connection, until eventually, if you are like me, arriving at a point where London feels more like home than anywhere else.

The Nigerian population in London has continued to grow. The 2021 census counted 266,877 Nigerian-born residents in Britain, a number not accounting for their children and relatives born here. It is thought to be the largest Black population in Britain, with a presence in nearly every borough of the capital. The football leagues across London reflect this dynamic: British-Nigerians turning out for clubs across the city, chasing Premier League pipedreams.

And so now, when the question of international allegiance is raised, footballers are confronted with two paths: to play for Nigeria, or to break new ground, and pull towards England, a dance between heritage or home. In the tournaments of the past decade the British-Nigeran presence in the England squad has deepened. Tammy Abraham and Eberechi Eze, both from south London, have played for the national side, as has Bukayo Saka. Dele Alli and Fikayo Tomori, who built their careers at Tottenham and Chelsea, have featured also. By pulling on the jersey, they carry these stories of migration and emerging identities into the light. They have formed a space for the national team to exist within us, the Three Lions no longer a distant afterthought on the edges of our imaginations. In my memory now I carry flashes of the most recent moments that have defined English football, the run to the semi-final in the 2018 World Cup and successive Euro finals in 2020 and 2024.

For some, there is a sense of pride and care for a new generation of Black players choosing to navigate the complicated, and at times threatening, spectacle of English international football. Among these players, Bukayo Saka is the most decorated. Raised in west London, he has emerged in recent years as Arsenal’s most gifted player. He takes centre stage for both club and for country. He is a sign of the Nigerian presence, an existence that surfaces subtly. During the BBC broadcast of England’s Euro 2024 quarter-final v Switzerland, the meaning of his Yoruba forename was retold on air to the 16.8 million people watching, the commentator, Guy Mowbray, noting that in English, “Bukayo” translates to “adds to happiness”. Nigeria, for the first time, is woven into the heart of the national footballing story.

And yet, there has been resistance. After the Euro 2020 final, when Saka missed the defining penalty against Italy, he and the other Black players suffered extreme racist abuse, a reminder of what we all knew instinctively, that though we have created home here in London, our foundations are fragile. In the dying embers of empire a heated resentment of our existence continues.

The innit innit boys have endured challenges too. When Nigeria fell in the 2023 African Cup of Nations final to Ivory Coast, a game I watched at a bar in east London, the British-born players were subjected to abuse online, and from the government. In the wake of the final, the Nigerian sports minister, John Enoh, speaking about the players born abroad, left his people with a question: “Do they have the spirit, the fire of a Nigerian player born in Nigeria?”

In such moments, we stare down a sobering reality: that we are not wholly of home, that our absence has consequences. There is a distance from the place where our stories began. It is a subtle parting of the waters. Here, in these new lands, we must find belonging again. And so, we lean in on ourselves, on what has been created here, on what London has made of us, and what we have made of it. This discovery of self, this carving out of home, is a feeding of the spirit. It is a means of survival, a remembrance for all those who journeyed here, and all those who are yet to come.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Italian in The Passenger Londra, a book-magazine that brings together investigative journalism and narrative essays about a country or a city, published by Iperborea.

3 months ago

48

3 months ago

48