It reads like an inventory of Donald Trump’s first two months back in the White House.

A newly elected demagogic president, renowned for his rabble-rousing rallies and provocative stunts, makes a whirlwind start on taking office.

He upends the country’s international relations in a series of undiplomatic demarches.

State institutions are gutted or closed in an outburst of radicalism aimed at transforming government.

Law enforcement authorities stage performative public roundups of those deemed, accurately or not, to be violent criminals.

Critics complain of statutes being routinely broken. Universities and media are targeted in a clampdown on free expression.

A widely revered cultural institution undergoes a government takeover and is given a conservative makeover.

Wrongfooted opposition politicians try to recover ground by highlighting the rising cost of dietary staples and the failure to address the kitchen-table issues that voters elected the president to solve.

Fitting as all this might be as a summary of the helter-skelter opening phase of Trump’s second presidency, it also describes events that followed the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as president of Iran 20 years ago.

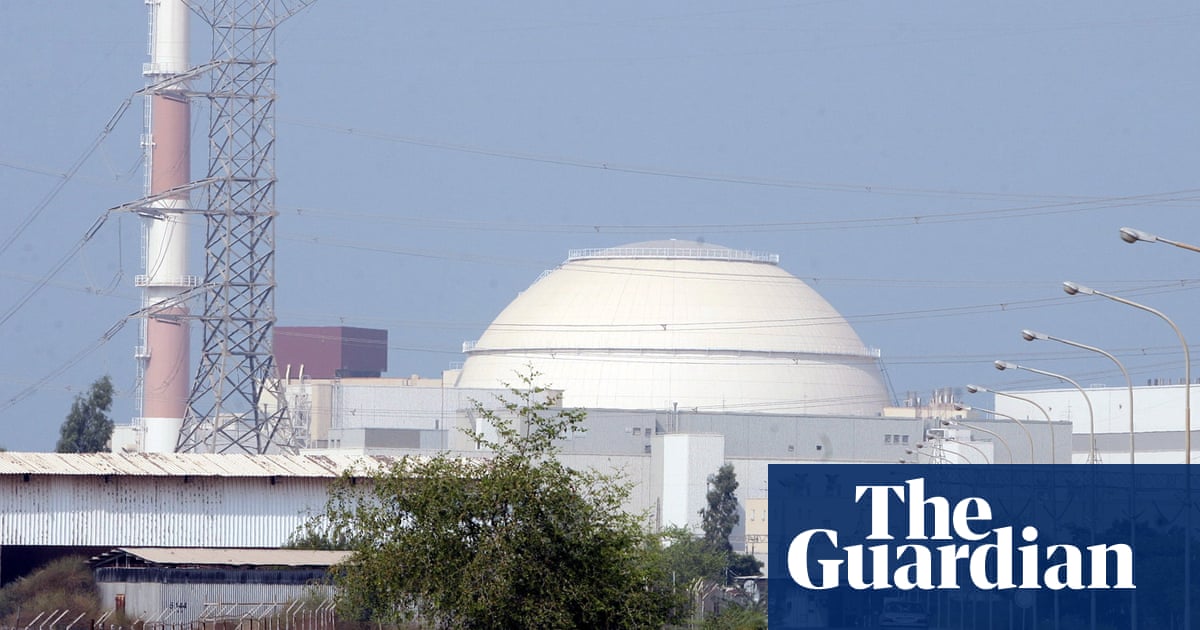

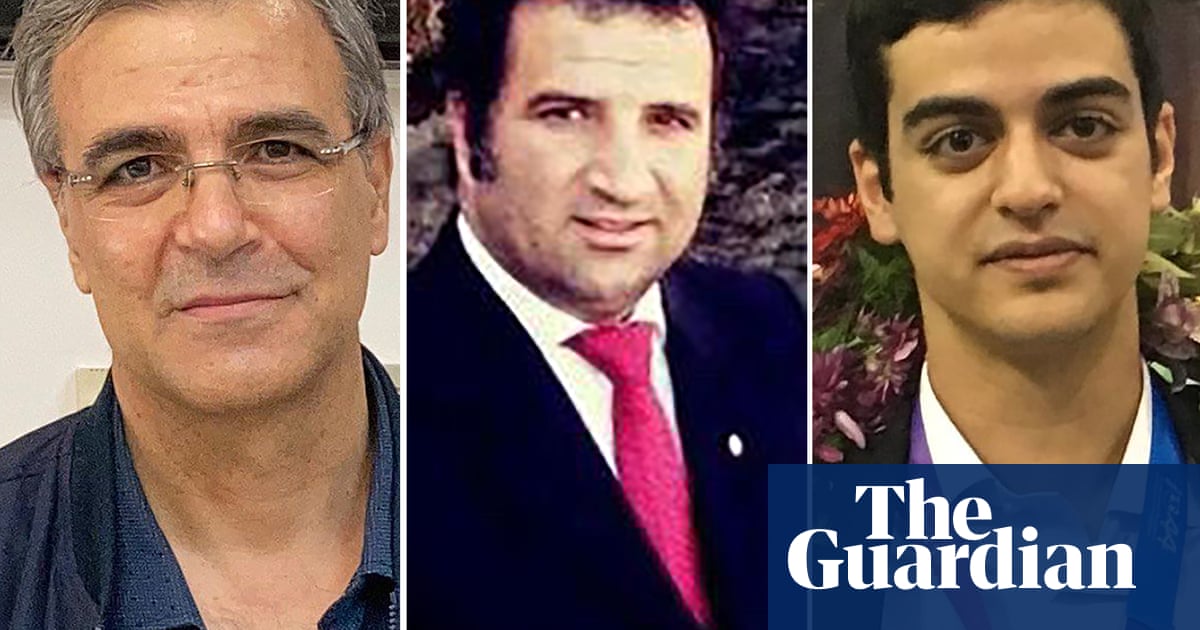

Ahmadinejad emerged as an arch-nemesis of the west after rising to power from obscurity in 2005. His offensive diatribes against Israel – which he suggested should be erased from the map – and repeated denials of the Holocaust were the stuff of cartoon villainy, sharpened further by his hawkish championing of Iran’s nuclear programme.

He was also an electoral populist in the Trump mould, as adept at drawing vast crowds with his message of championing the left-behinds and dispossessed as he was at riling his opponents.

Iranians have noticed the matching personas. “There was a joke in Iran during Trump’s first term that when he became president, Iran finally managed to export its revolution,” said Vali Nasr, an Iranian-born international affairs scholar at Johns Hopkins University. “Trump was basically Ahmadinejad in the US.”

In a striking twist, Ahmadinejad even addressed Columbia University – an institution now threatened with grant cuts by the Trump administration over an alleged failure to combat campus antisemitism by tolerating pro-Palestinian protesters – in a 2007 visit to New York. The university’s then president, Lee Bollinger, assailed him to his face for his Holocaust denial and called him a “cruel and petty dictator”, a description that seemed to presage the criticisms of many of Trump’s opponents.

The parallels, however, are superficial – and the differences just as significant.

Ahmadinejad, remembered for his trademark man-of-the-people white jacket, defined himself by his frugality and surrounded himself with like types; Trump flaunts his wealth and seems to have space in his inner circle for billionaires, for whom he favours huge tax cuts.

Moreover, any comparison between Iran and the US must come with a health warning.

Iran, under the stifling religious regime that seized power after the 1979 revolution that toppled the country’s former pro-western monarch, Shah Mohammad Pahlavi, was hardly a flourishing democracy before Ahmadinejad’s presidency – even after a period of relatively liberal reform under his predecessor, Mohammad Khatami.

“He came to power in an already deeply authoritarian regime,” said Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who was in Iran when Ahmadinejad became president. “He took what was already a seven on the repression scale and made it a nine.”

Yet the fact that any analogy can be drawn at all attests to the uncharted territory the US has entered under Trump.

In recent weeks, as the president and his allies have assailed judges and hinted that they could flout court rulings, commentators and experts have warned of a looming constitutional crisis and lurch towards authoritarianism and even dictatorship.

Scholars have touted a variety of global precedents in a quest for a parallel that might act as a guide for where US democracy is headed.

after newsletter promotion

Commonly cited examples are Hungary and its strongman prime minister, Viktor Orbán; Turkey, whose president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has held power for 22 years and has purged the judges and military general who upheld the secular state structure created by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk; and Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin. The ascents of all three are often viewed as instances of democracies and once-independent institutions being emasculated and elections gamed to sustain the incumbent.

More encouraging portents are seen in Poland and the Czech Republic, where rightwing populist nationalist forces lost power in the most recent elections to parties or presidential candidates committed to the liberal democratic mainstream and to international institutions such as the EU and Nato.

Yet none seem to rival the sheer ferocity with which Trump has eviscerated federal agencies, denounced judges and churned out landscape-changing executive orders.

The problem was summed up by Steven Levitsky, a Harvard political scientist and author of books on democracy’s decline and autocracy’s rise, who told the New York Times that he had seen nothing like Trump’s assault on democratic institutions.

The first two months under Trump had been “much more aggressively authoritarian than almost any other comparable case I know of democratic backsliding”, he said. “Erdoğan, [Venezuelan leader Hugo] Chávez, Orbán – they hid it.”

Other observers agree that Trump’s moves are of greater magnitude than those seen in other democracies turned autocracies.

“The best parallel that I can see is the collapse of the Soviet Union,” said Nader Hashemi, professor of Middle East and Islamic studies at Georgetown University and another academic of Iranian origin.

“A political order that everyone thought had a long shelf life rapidly collapses, is completely disorienting, and people are trying to figure out what comes next.

“We don’t really have precedents similar to this moment where you have a longstanding existing democracy that’s a major power that collapses so rapidly and quickly and is moving in the direction of authoritarianism. I think its impact will also be felt globally.”

Nasr said Trump confounded comparisons with previous democracy-subverting authoritarians, likening the current White House to the court of King Henry VIII, the 16th-century monarch recalled for his six wives and for triggering the English reformation.

“The way he’s setting up authority in the White House looks more like a Tudor monarchy than modern authoritarianism,” he said. “The White House looks more like an imperial court.”

Trump, argued Nasr, “has a theory of rapid, massive change” that recalled the approach of military coup leaders in the third world who judged that their agenda was incompatible with democracy.

The common bond between Trump and Ahmadinejad may be the forces that brought them to power.

“One could say that the very first kind of backlash in our era against what economic liberalisation can do to a society happened in Iran,” said Nasr.

Under Ahmadinejad’s two presidential predecessors, Khatami and Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, liberal economic reforms intended to generate prosperity after years of post-revolutionary austerity produced an affluent, consumerist middle class – but left behind a disaffected population group that felt it had lost out.

“It created a class in Iran much like the people who voted for Brexit [in Britain] or people who voted for Trump,” Nasr said. “So [Ahmadinejad] was anti-establishment in the way Boris Johnson was during Brexit, or Trump was during his two campaigns. There is definitely a parallel there.”

Hashemi saw another parallel in Trump’s attacks on universities and the media – a trend which Iran witnessed (accompanied with much greater repression) even before Ahmadinejad took power, as hardliners tried to snuff out the freedoms that reformists had introduced.

“Then Ahmadinejad comes and continues in an authoritarian direction,” he said. “The parallel between that period and now in the United States is that authoritarian regimes hate independent institutions, the press and particularly universities, because they foster free thinking, they hold power to account. That’s why we’re seeing this attack on Columbia University and other universities.”

Ahmadinejad, having stoked inflation with populist cash handouts and facilitated the Revolutionary Guards’ takeover of the economy, was ultimately thwarted by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader and most powerful cleric, who marginalised him while using Ahmadinejad’s authoritarian impulses to accrue more autocratic powers to himself.

Trump – having subjugated the Republican-ruled Congress, and who is now limited only by a constitutional bar on seeking a third term that some of his supporters are already clamouring to amend – is subject to no such constraints.

“In a way, Trump’s conduct is more sinister because he’s trying to turn a democracy into an autocracy,” said Sadjadpour. Given the odium in which Ahmadinejad’s detractors once held him, it seems a particularly ominous verdict.

2 months ago

46

2 months ago

46