The cloth cap and blazer-wearing line judges of Wimbledon are as much an icon of this famous old sporting event as the manicured lawn courts. But this, the 138th tournament in its storied history, was the year SW19 took a leap into the 21st century – replacing some of their judges with an electronic line-calling system that was supposed to put an end to human error.

Now, as the sun sets on this new era at Wimbledon, many of the headlines have been about just that. Mistakes have been blamed on the people operating it, much to the ire of players forced to replay points that were sabotaged by the faltering Hawk-Eye.

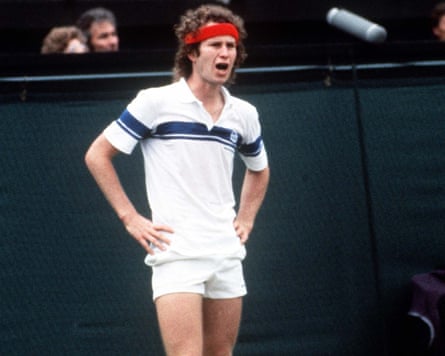

The irony has not been lost on one former line judge. Pauline Eyre’s beady eye was once trained on swerving kick serves from the likes of Jimmy Connors; this year she watched from afar, and in exasperation.

“You cannot just keep taking away anything that makes it human in order to create some kind of perfection for players who are also flawed, that’s what they have to deal with, that’s what sport is,” said Eyre, who worked as a line judge for 20 years, spanning 16 Wimbledon championships and 12 finals.

“Sport is about people,” she said. “The principle is more important than the very occasional difference to one call.”

In many ways, Wimbledon is falling in line with other professional tennis tournaments, including the Australian Open and US Open, which also use automated ball-tracking technology known as electronic line-calling or ELC. The French Open remains the only grand slam that still employs human line judges.

Wimbledon uses the ELC provider Hawk-Eye, which has 10 cameras around the court and tracks the bound of a ball to a margin of error of 2.2mm. Previously, ELC was used as a safety backup when players had challenged calls by line judges.

But at this year’s debut, players were forced to replay points at crucial stages after an operator unintentionally switched off a set of cameras with one computer click. The technology has since been overhauled so that cameras cannot be turned off when the system is operational.

For Eyre, it’s not just the sometimes theatrical tradition of players challenging calls that is lost, or the distinctive uniform seen across the grounds, but the personnel as well.

Some of the line judges, formerly numbering 300, who became court assistants are no longer putting their specialised expertise to use, she said, and for the players, there are no visual cues confirming each call on court.

after newsletter promotion

“It’ll always need humans,” Eyre said. “And what you’ve got then is humans in an underground bunker pressing buttons instead of humans standing on a court in the fresh air, visible.”

During this year’s tournament, Emma Raducanu expressed her disappointment that “the calls can be so wrong” after her loss to top seed Aryna Sabalenka. Jack Draper said it was a “shame” that the tradition of umpires was lost and said it’s easier for players not having to worry about line calls.

A spokesperson for the All England Club said the decision to introduce live electronic line calling was made after a significant period of consideration and consultation, and acknowledged the “vital” role line officials played at the tournament for decades.

“For the players, it offers them the same conditions they play with on tour and, crucially, this is what the players want and expect,” the spokesperson said. “Ultimately, live electronic line-calling is by far the most accurate way to call the lines on a tennis court, and that’s why tennis has, and is, adopting this system.”

What is next, wondered Eyre, whose career is now in comedy: “Should we replace the royal box with AI? Should we replace the ball kids with a machine that will throw the ball at you?”

Attending the championship for the third time, travelling from Scotland, tennis fan David Cullen said he agrees with the technology in principle, for its efficiency and reliability. Aesthetically, it was good to see the line judges on court and the interactions with players on court, contended Jane Carter, 58, outside No 1 Court.

“I would think that it would improve with use over time,” replied Cullen, 62. “AI, unfortunately, is the way it’s going to go for all sporting events,” he added, lamenting the use of VAR in football, which he said slows down the game.

Standing beneath the shade of No 1 Court, Tom Mansell said the technology takes the “fun out of it” and said the more jobs for people, the better.

“If there’s going to be errors either way, then why can’t it be a human making the decision?” said Mansell. “It’s a skill as well, actually, being a judge,” he added. “We’d much rather keep that alive than lose it.”

3 months ago

51

3 months ago

51