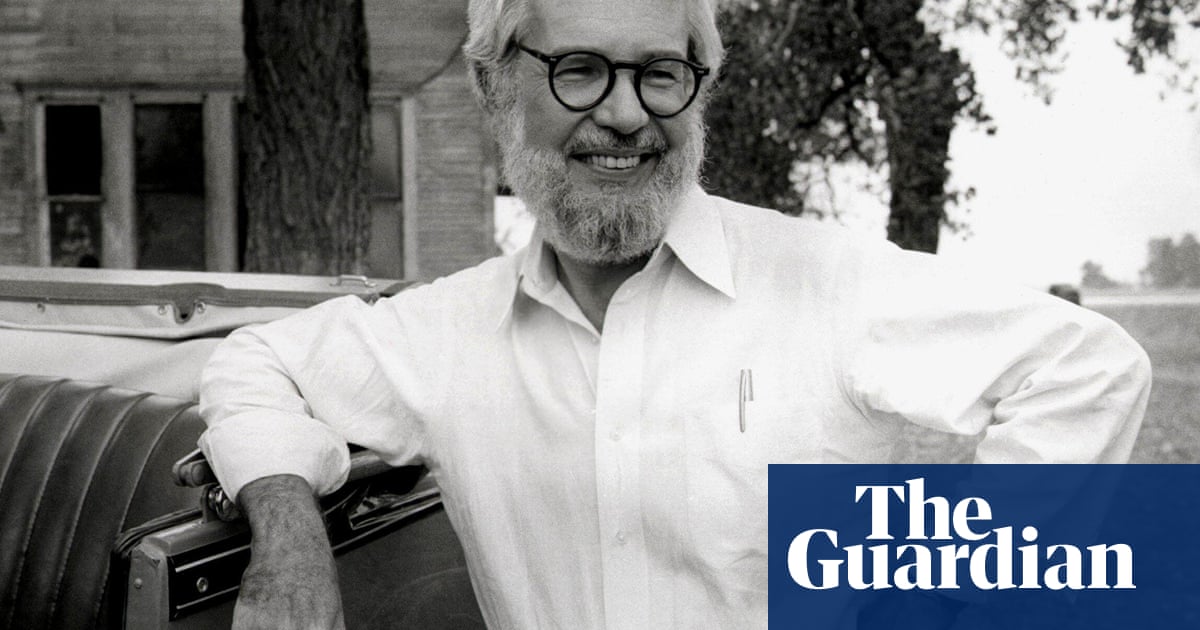

A straight-backed, well-spoken former management consultant and ex-soldier in a wax jacket might not resemble much of a tree wizard, but the man leading me into a steep Cornish valley of gnarled, mossy oaks is called Merlin. He possesses hidden depths. And surfaces. Within minutes of meeting, as we head towards the Mother Tree – a venerable oak of special significance – Merlin Hanbury-Tenison reveals that he recently had a tattoo of the tree etched on his skin. I’m expecting him to roll up a sleeve to reveal a mini-tree outline, but he whips out his phone and shows me a picture: the 39-year-old’s entire back is covered with a spectacular full-colour painting of the oak. “It took 22 hours. I was quite sore,” he says, a little ruefully. “But I was in London afterwards, feeling quite overcome by the city and I had this moment: I’ve got the rainforest with me. Wherever I go, I feel like I’m carrying the forest and its story with me.”

Merlin is keen to tell the remarkable 5,000-year story of this fragment of Atlantic temperate rainforest – a rare habitat found in wet and mild westerly coastal regions and which is under more threat than tropical rainforests. In fact, he is now the custodian of this special, nature-rich landscape filled with ferns, mosses, lichens and fungi. He is slightly more reticent about his own remarkable life. Both stories are well worth telling.

Cabilla, a 250-acre hill-farm on the edge of Bodmin Moor, was bought in 1960 by his dad, the explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison. He wanted a place where he wouldn’t hear traffic and could drink from the stream. The call of a song thrush, not traffic noise, fills the valley to this day and Robin, now approaching 89, still drinks from the stream. Merlin has taken over the farm and has conjured up three big visions: he wants to expand the less-than-1% fragment of Atlantic rainforest that endures in western Britain; he hopes to demonstrate that a new kind of hill-farming is viable and employs local people; he also seeks to open up such forests to those who need them the most – the traumatised, the broken and stressed urbanites who don’t even realise they can thrive if they take time beneath an ancient tree, imbibe the smell of damp leaves and listen to the river dancing over the ferny rocks below.

As Merlin writes in Our Oaken Bones, a graceful and inspiring memoir, the epiphany that trees were his life’s work was slow in coming and it arrived in a crisis. Merlin was born on his parent’s Cornish farm and loved playing with his dogs in the woods. Aged seven, he was sent to boarding school. There he dabbled in acting, starring as Russell Crowe’s son in the film Proof of Life (Crowe – “a lovely man” has offered words of praise for his first book). Then Merlin joined the army, partly because the terror attacks of 9/11 made a big impression on his 16-year-old self, but also because of a claim in FHM magazine that “tank commander” was a job that young women rated particularly highly.

He undertook three tours of Afghanistan. In 2007, his armoured vehicle hit a landmine. Momentarily blinded and deafened by the explosion, he remembers sitting in the debris urgently feeling his body for puncture wounds to stop the blood loss that would rapidly prove fatal. He was covered in a thick liquid. With a sense of doom, he knew it was his own blood. He licked it from his fingers. He must have been concussed and confused: the liquid tasted like English mustard. It was English mustard, which had splattered everywhere from a jar stored in the vehicle. “I still can’t eat mustard,” he says. “Trigger is not really a term I tend to use, but it definitely pulls me into a moment that I would rather not be pulled into.”

When Merlin had received some fairly cursory army trauma training, he was sceptical to be told that the full effects of a catastrophe might not manifest itself in a person for a decade. After the explosion, he was fine. He didn’t break down. He never cried. “I’d spent 20 years, from seven to 27, in institutions where if you cried, that was bad,” he says. “If you were seen to be crying, it was definitely not going to raise your social status or raise your ability to survive. And in the military, I was a leader. I was put in charge of soldiers at 19. I couldn’t be seen to cry in front of them.”

When he was in the military, he met and married Lizzie, a move which spurred him to leave the army and become a management consultant in London. Then, in 2017, a decade after he was blown up, on a high-pressure project, disconcerting memories started returning. Eventually, he broke down for the first time in his life, in front of a senior management consultant. He was advised to see the doctor and take some pills; then he’d be fine. Merlin knew he was not fine. He left the project and went down to Cabilla for a break. It was not good for his career. “It’s viewed very badly, because it doesn’t look like you’re striving, fighting, thriving,” he says. Back on the farm, which has 85 acres of valley woodland and 165 acres of grazing pasture, he “spent time walking, sitting, swimming, being. Then I noticed things that needed doing – fences to mend, a gate that had fallen down and I started in an incompetent way to fix them.”

Meditation didn’t really work, but he discovered that hunting roe and red deer was meditative for him. It also helped stop the deer devouring the next-generation oak trees. “I found when I’m in this valley on my own with a rifle looking for a deer that’s eating all the oak saplings, I can’t be worrying about the past. I have to be in that moment,” he says. He likens it to traditional hunter- gatherers and argues there’s not as big a gulf between this and mindfulness as most people would think.

In Cabilla’s woods, Merlin felt his “body slipping into the parasympathetic ‘rest and digest’ state. I hadn’t realised how much my body needed it. I hadn’t realised how much everybody needs it,” he says. As we stroll through the oaks, which are stout and low, their wintery branches coloured peppermint by lichen, Merlin is careful not to claim his experience was a nature cure.

“When I talk to people about being blown up in Afghanistan, they say [of the PTSD], ‘That makes sense’, but mental health is never as simple as two plus two. It’s not ‘I was blown up and have PTSD and nature cures me.’” His PTSD was also caused by his stressful job and city lifestyle. Eventually, he quit the consultancy job and focused on his recovery. He took talking therapy and found sound therapy and eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy to be useful as well. He turned down antidepressants. “I’d never want to imply that people shouldn’t go with medication, but for me I wanted it to be the last thing I tried,” he says. Instead, he attended a psilocybin [magic mushroom] retreat in Amsterdam. “It was without doubt the most transformational moment of my life,” he says. “I’d never use the word ‘cure’, but it put me into a very stable state of mental health for a longer period than anything else.”

While Merlin was seeking to restore his mental health, Lizzie suffered the trauma of repeated miscarriages. She came to Cabilla to recuperate, too, and they had an epiphany. “It’s a place of healing. It’s healing people and it’s a place to heal the land,” he says. In 2020, they both moved down to Cabilla and established a wellness retreat. Over the past four years, while juggling two young daughters, they’ve hosted 3,000 people. In the woods, they provide courses for NHS nurses, US special forces and business people, as well as yoga and Wim Hoff breathwork sessions for paying guests. The forest seems to attract those who need it. “We’re in the kitchen having breakfast with the girls and some druid wanders past the window. That’s Cabilla,” laughs Merlin. But his “favourite people” who come on retreat “are those who don’t think they like nature”. And he’s proud there is “at least a 60% tear rate among the people who come here, a positive natural outpouring. I cry all the time now”.

The land-healing part comes through Merlin’s charity, the Thousand Year Trust, which is dedicated to nurturing and expanding the Atlantic rainforest fragments not just around Bodmin Moor but across the hills and valleys of western Britain, which was cloaked in this rare and biodiverse habitat a millennia or two ago.

We have reached the Mother Tree. “She’s not the biggest or the oldest, but for me there’s something about this tree. She’s a sentinel,” says Merlin. “She is holding so much on her. She is the most wonderful condensed example of a rainforest.” The oak is in early middle-age, a mere 370 years old, and her branches are already covered by ferns, lichens and clumps of moss the size of a wildcat. Like other native oaks, she could support several thousand species: fungi, beetles, birds, wasps, butterflies. One short dead stump of a branch alone hosts eight different rare lichens.

Like other surviving rainforest fragments, Cabilla endured by chance, because it grew in a valley too steep and filled with granite boulders to be cleared or cultivated for farming. Peat core samples have proven there has been forest cover here for at least 3,664 years – and probably since the ice age. Perhaps the forest also survived because it was beautiful and sacred. There are six ancient stone monuments in the valley dated to 4,500 years ago.

For the first time in perhaps 1,000 years, Merlin is expanding Cabilla’s woodland. Pastures have been planted with young oaks, with other areas left to naturally regenerate. Following the model established by the rewilded estate of Knepp, Merlin will bring back grazing cattle, horses and pigs, but only once the regenerating trees are established. There is still scepticism among some local farmers and Merlin questions what he’s doing. “Is it good farmland and am I ruining it? Well, grade four agricultural grazing land is not good farmland, it’s appropriate for sheep and a few cows. Are we ruining it? I don’t think planting 100,000 trees and sequestering thousands of tonnes of carbon is ruination.”

He wants to prove that people can be part of this picture, too. He wants valleys of rainforest corridors connecting fragmented remnants and low-density livestock grazing that provides high-welfare, very high-quality meat – “Cornish rainforest beef” – that can be sold directly to consumers for a good price. He hopes that this “agro-rainforestry” (“It’s not taking off as a term yet,” he laughs) will “create a blueprint for what might work for farmers in some of our western uplands”. Local landowners with 6,500 acres between them have joined a farm cluster that’s enthusiastic about restoring rainforest along Merlin’s lines.

We head deeper into the forest. A squall approaches. Suddenly, we’re not in rainforest but hailforest. Just as abruptly, a brilliant rainbow appears, pointing to a pot of gold in the valley bottom. Is there money in Merlin’s big ideas? He crunched the conventional farm numbers and found he couldn’t make a living from sheep and cows. In 1960, the farm employed eight people. When Merlin took over, there was one seasonal farm worker. Today, Cabilla employs nine people on its retreats business, with five more working for the charity. Cabilla is also a focus for a new generation of temperate rainforest scientists. Last year, they hosted six universities and six PhD students, alongside 20 MScs – this year they hope to double that.

As well as promoting a new scientific understanding of temperate rainforests, Merlin aims to inject a spiritual dimension into our thinking. Leading writers, including Robert Macfarlane, whose powerful new book Is a River Alive? is published this spring, are urging a change to western mindsets, so that we recognise that ecosystems and habitats and rivers are living wholes, and deserve our gratitude and devotion rather than simply being exploited in the service of human wealth or wellbeing. “There’s still this barrier in people’s minds that humans aren’t part of these kinds of places and aren’t part of nature,” says Merlin. “I want to help people remember and create that societal memory that we are a rainforest people living in a rainforest island. Being here is far more natural than getting a coffee on a busy high street. Every place on the planet has special pinnacle habitats, which we should love and care for and view as living entities in themselves. This forest is a 4,000-year-old living entity. It’s a giant mushroom with thousands of fingers pointing in the air. Our purpose is to make sure that with each human generation it is slightly bigger, more biodiverse and more harmonious.”

Just as the rainforest may be a living whole, so the Mother Tree possesses her own will and personality. For Merlin, she embodies Cabilla “which is why I spent 22 hours of pain having her put on me forever, much to my wife’s chagrin,” he grimaces.

Time moves slowly for the Mother Tree and her neighbours. “It’s frustrating, because there will never be enough time with Cabilla. You need 500 years to watch trees evolve and grow,” he says. But with luck, Merlin and Lizzie’s daughters will see Cabilla in 80 years’ time, when today’s vision is fruiting and burgeoning and a rainforest nation is more enthusiastic than ever about its regrowing forests. At least their eldest is enthusing about her dad’s tattoo. Merlin laughs. “She says, ‘My daddy carries a rainforest on his back.’”

Our Oaken Bones by Merlin Hanbury-Tenison is published on 20 March at £22, or £19.80 at guardianbookshop.com

2 months ago

40

2 months ago

40