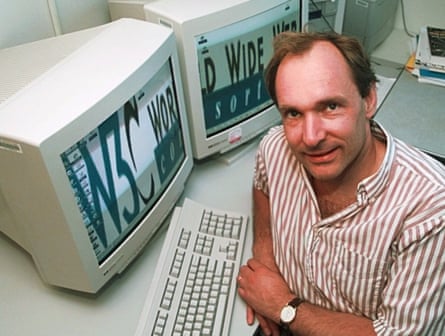

When Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented the world wide web in 1989, his vision was clear: it would used by everyone, filled with everything and, crucially, it would be free.

Today, the British computer scientist’s creation is regularly used by 5.5 billion people – and bears little resemblance to the democratic force for humanity he intended.

In Australia to promote his book, This is for Everyone, Berners-Lee is reflecting on what his invention has become – and how he and a community of collaborators can put the power of the web back into the hands of its users.

Berners-Lee describes his excitement in the earliest years of the web as “uncontainable”. Approaching 40 years on, a rebellion is brewing among himself and a community of like-minded activists and developers.

“We can fix the internet … It’s not too late,” he writes, describing his mission as a “battle for the soul of the web”.

Technology isn’t neutral

Berners-Lee traces the first corruption of the web to the commercialisation of the domain name system, which he believes would have served web users better had it been managed by a nonprofit in the public interest. Instead, he says, in the 1990s the .com space was pounced on by “charlatans”.

“The Americans were very keen about commercialising the internet … crossing the boundary from being an academic thing to being a commercial thing,” he tells Guardian Australia from Brisbane.

The pursuit of profit soon became a driving force in how the internet was designed. But it wasn’t until 2016 – the same year he won the Turing award – that the US elections showed Berners-Lee just how toxic the web could be. Two years later, he told Vanity Fair that he was “devastated” by the abuses of the web.

For 35 years, Berners-Lee has written what he considers to be the world’s first blog. One post, published in June 2024, is dominated by a crowded map of “everything on the internet”. It is a reminder of the web’s overall beneficence – from email and Zoom to health, podcasts, collaboration, creativity and digital sovereignty, the diagram shows the web is, for the most part, good.

But to the left of the diagram is a cluster of red, including X, Snapchat, YouTube, “feed manipulation for engagement”, addiction, polarisation, disinformation and mental illness. This corner of the web, its creator says, has been “optimised for nastiness”. It is extractive and surveillance-heavy.

“It’s only a small part of the whole internet … but the problem is that people spend a lot of time on [social media websites] because they’re addictive,” he says.

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

Given it was always supposed to be human-like in its sprawling connectivity, perhaps its darker sides were inevitable.

“Yes and no,” Berners-Lee says. “There used to be a sort of mantra that technology was neutral and people are good and bad. But actually, that’s not true of things on the web.

“The way you design a website, like Reddit or Pinterest or Snapchat, can be explicitly good.” Or, designed with engagement as a priority, its algorithm can be explicitly bad.

Collaboration and compassion

Compounding the problem is monopolisation. Facebook and Google’s dominance is bad for innovation and bad for the web, he says, because monopolies get in the way of building systems that are truly pro-human. How many companies, after all, hold your (identical) data in non-transparent and incompatible systems?

Since Berners-Lee’s disappointment a decade ago, he’s thrown everything at a project that completely shifts the way data is held on the web, known as the Solid (social linked data) protocol. It’s activism that is rooted in people power – not unlike the first years of the web.

This version of the internet would turbocharge personal sovereignty and give control back to users.

“When people are excited, they get a twinkle in their eye and they start coding just because of what they can imagine,” he says of developers who “get” the concept.

He likens Solid “pods” to backpacks of data that are securely held by each individual, allowing them to choose what to share with certain people, businesses and organisations. Department of Education data could be shared with an AI tutor; medical data with a cousin, doctor and nutritionist. The Flanders government in Belgium treats data as a national utility and is already using Solid pods for its citizens.

The Facebooks and Xs of the world need not join in – the new systems will be so empowering, collaborative and compassionate, he believes, that parts of today’s web will become obsolescent.

“The existing systems will fade to a certain extent, because people will get more excited in new systems,” he says.

“Being able to collaborate across the world with friends and family and colleagues will be something that they end up getting addicted to – a much better form of addiction.”

He’s not the only person wanting to fix these problems. Australia’s world-first social media ban – which blocks under-16s from using a host of sites including Snapchat, X, Facebook and YouTube – is one attempt at a solution. Although Berners-Lee is not convinced.

“I’m interested to see how it goes down in Australia, because there are people in the UK who are proposing it in a similar way, and others may follow on,” he says.

“The first question is whether kids should be using those particular social media sites. I think you have to recognise that things like messaging services are useful.”

Instead, he’s in favour of smartphones that are especially designed for children, blocking access to harmful sites. He points to the Other phone, designed in collaboration with Mumsnet users, as an alternative to devices that allow unfettered access to social media.

The AI ‘horse is bolting’

It’s on the subject of artificial intelligence that his optimism plummets.

Berners-Lee has long seen AI – which exists only because of the web and its data – as having the potential to transform society far beyond the boundaries of self-interested companies. But now is the time, he says, to put guardrails in place so that AI remains a force for good – and he’s afraid the chance may pass humankind by.

“The horse is bolting,” he says of reining in AI’s unchecked development and growing intelligence.

Berners-Lee created the web, HTML and HTTP at Cern, the home of the Large Hadron Collider, on the outskirts of Geneva. Cern’s scientific, non-commercial approach was key to the way the technology was shared.

“I would like to see a Cern for AI, where all the top scientists come together and see whether they can make a super intelligence. And, if they can, they contain it into a system where it can’t just go out and persuade people to let it run the world.”

Right now, though, given the division sown in part by that red corner of the web, we are “very, very far from a Cern for AI”, he says.

“We have got AI being done in these huge companies, but also in these huge silos. They’re not looking over each other’s shoulder. They’re just sitting there, inside their own company, looking at their own system, trying to make it smarter.

“I don’t see a way that we can get to a point where the scientific community gets to look at the AI and to decide whether it is safe or not.”

Sir Tim Berners-Lee will be speaking at the Brisbane Powerhouse on Thursday 29 January and the Sydney Opera House on Friday 30 January

2 weeks ago

27

2 weeks ago

27