In one corner, friends discuss the aftermath of last week’s visit by Donald Trump Jr, while in another, coffee is being roasted, as the northern lights dance across the dark early evening sky. Suddenly, a group at the neighbouring table, who have broken off their game of backgammon to take a video call, erupt into excited squeals. The rest of the coffee shop responds enthusiastically.

“There was a big catch of narwhals,” explains Aka Hansen, an Inuit film-maker. “Welcome to Greenland.”

Trump Jr’s brief visit to Nuuk, the Greenlandic capital, and the subsequent comments by his father, US president-elect Donald Trump, who takes office on Monday, reiterating his interest in acquiring the world’s largest island and threatening military action to do so, have sparked mixed opinions in this Arctic autonomous territory.

But what nobody seems to disagree on is the global spotlight it has put on Greenland, its geopolitical strategic importance, and its relationship with Denmark, which formerly ruled the island as a colony and continues to control its foreign and security policy.

It is a moment that the pre-existing independence movement – and those whose years of protests against racist practices against Greenlanders, both current and historic, have for so long gone ignored – do not plan to waste.

Just last weekend, Hansen says, they were unable to get Copenhagen to say anything about highly controversial “parenting competency” tests, known as FKU – psychometric tests widely used in Denmark as part of child protection investigations into new parents, which have long been criticised by human rights bodies as culturally unsuitable for Greenlandic people and other minorities.

On Sunday, after years of inaction, the Danish government reached a joint solution with the Greenlandic government, Naalakkersuisut, about the use of the tests on Greenlandic families and has said it will submit a bill on it in the current parliamentary session.

“All of a sudden, now there’s an agreement on the table,” says Hansen, incredulous. “Which seems magical and also weird at the same time, because why wasn’t that possible before Trump’s visit?”

And on Thursday, it emerged that the Danish government was reportedly working on an action plan against racism, with a particular focus on racism against Greenlanders it said was “an overlooked problem”.

But there is still a lack of action on the IUD scandal, labelled a genocide by the Greenlandic prime minister, in which 4,500 women and girls were allegedly fitted with contraception without their knowledge or consent between 1966 and 1970.

Trump’s intervention has highlighted how the very concept of ownership of the land – by themselves, the US, Denmark or anybody else – is repugnant to many Greenlanders.

Actor Miké Thomsen prompts agreement from around the table when he says: “Ownership, it’s not in our mentality. To own land, we don’t, we’re not, I don’t even know how to say. It’s just,” he pauses, “not in our mind.”

It is, says Paninnguaq Korneliussen, a student who is sat in a sofa with her six-month-old baby in her arms, “unfathomable”.

“It’s not in our vocabulary to say that we own this. It’s not in our mind as well,” she adds.

“And to hear people outside this saying ‘we want to buy this land’, you can’t even describe how wrong it is because it’s not in our culture, it’s not in our mentality. You don’t own people. You don’t own land.”

That does not mean they rule out collaboration with the US – or other countries for that matter – though. There is a sense that the renewed US interest could help achieve independence, or at the very least force Denmark to improve its treatment of the territory. Already it has started to change the rhetoric of Danish politicians.

“Human beings from all over the world should always be up for collaboration,” says Miké. But, he adds: “Never call it ownership or commonwealth, but keep it real. Let’s say: ‘Let’s talk about what we can do together.’”

In an interview with Fox News on Thursday, the Greenlandic prime minister, Múte Egede, said: “We don’t want to be Americans. We don’t even want to be Danes. We want strong cooperation between our countries.”

Reiterating his point, he added: “We want to be clear: we do not want to be Americans. We do not want to be part of the United States.”

Despite this, his appearance attracted the praise of far-right Republican and loyal Trump ally Marjorie Taylor Greene, who said it was a “fantastic interview” and that the US hopes for “future collaboration with Greenland and its wonderful people”.

Among many Greenlanders there is anger at the Danish reaction to Trump’s intervention, speaking on Greenland’s behalf and betraying the assumption that being part of the kingdom of Denmark is preferable to Greenland’s population of 57,000 than any potential association with the US.

In a 45-minute phone call with Trump on Wednesday that did not include Egede, the Danish prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, told him it was up to Greenland to decide its own future. She also said Denmark was prepared to increase its responsibility for Arctic security.

In a warehouse by the snow-covered Nuuk harbour, men are standing at tables attaching bait to hooks for catching halibut to the backdrop of the radio, overalls hanging on the wall. “What happens to Greenland should be up to the Greenlandic people,” says one. “Not up to the US or Denmark.” Trump, though, he adds, “is an idiot”.

In his new year speech, Egede said “important steps” towards independence should be taken in the upcoming election period. The Greenlandic population, he said, “must take a position and decide whether Greenland should take further steps towards an independent country”.

For his part, at a candlelit kitchen table in Inatsisartut, the parliament building, opposite a shopping centre in downtown Nuuk, Pele Broberg, the leader of Naleraq, Greenland’s largest opposition party, says he has been in touch with former members of the Trump administration. “They’re trying to figure out ‘what is it exactly we need to do to understand what Greenland wants’. Because they keep hearing about the independence thing, [but] nothing ever happens.”

If he were to win the 2025 parliamentary elections, to be held no later than 6 April, Broberg would first seek a mandate from parliament to notify the Danish government Greenland is leaving and then tell the US that Nuuk wants a defence agreement between the US and Greenland to take immediate effect after leaving Denmark. He would also want to set up trade agreements, including with the EU and the UK. The whole process, he believes, could take three years.

Greenland, he says, has long been used by Denmark as a “bargaining chip” with the US.

Some people have told him they do not see the difference between being under the control of the US or Denmark. But the majority, he says, want independence. According to polls, most Greenlanders are in favour of independence, but only if it does not come at the expense of welfare.

“They want to be their own people. Right now, we have a flag without a home. We have a flag and we’re recognised as a people but it’s not our land on paper.”

The difference between Trump’s last attempt to “buy” Greenland in 2019, says Broberg, is that this time he is “more informed”.

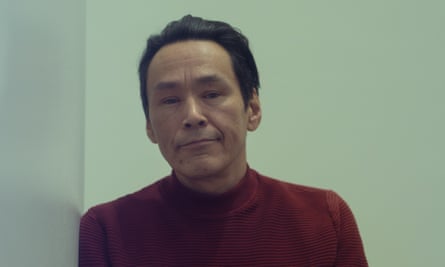

Over coffee at Katuaq, the cultural centre in Nuuk, the actor and musician Angunnguaq Larsen, who played the fictional Greenlandic prime minister, Jens Enok Berthelsen, in the Danish political drama Borgen, describes the period since Trump Jr’s arrival as “one of the most farout experiences that we ever had. Trump Jr came and suddenly all of it just exploded.”

Greenlanders, he says, have been telling Denmark it is racist for decades, but when Trump Jnr made that statement, it was suddenly on the front page of newspapers. “That’s hypocrisy,” he says.

Greenlandic politicians “must stand firm” but they must also leverage this moment carefully, he warns. “We have to use it wisely, this interest from the States, to gain more control of our own country and our future.”

3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57