By the early 1980s, the Democratic party was facing a crossroads. The 1980 landslide election of Ronald Reagan, who clenched the presidency with a whopping 489 electoral college votes against Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter, swiftly pulled the Democratic party to the right in the political and cultural wave of the “Reagan Revolution”.

For those Democratic constituents left behind, however, a challenge was mounting, mostly within US industrial cities whose economies were ransacked by Reagan’s “trickle-down” economics. Record tax cuts for the wealthy had come at the expense of a contracted social safety net, thus exacerbating inequality and collapsing much of the working class into the poor. Grassroots resistance campaigns spawned across the country in response to this dire urban crisis that had disproportionately devastated African Americans, and between 1982 and 1984 they had registered 2 million new Black voters – the largest gain in registered Black voters since the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

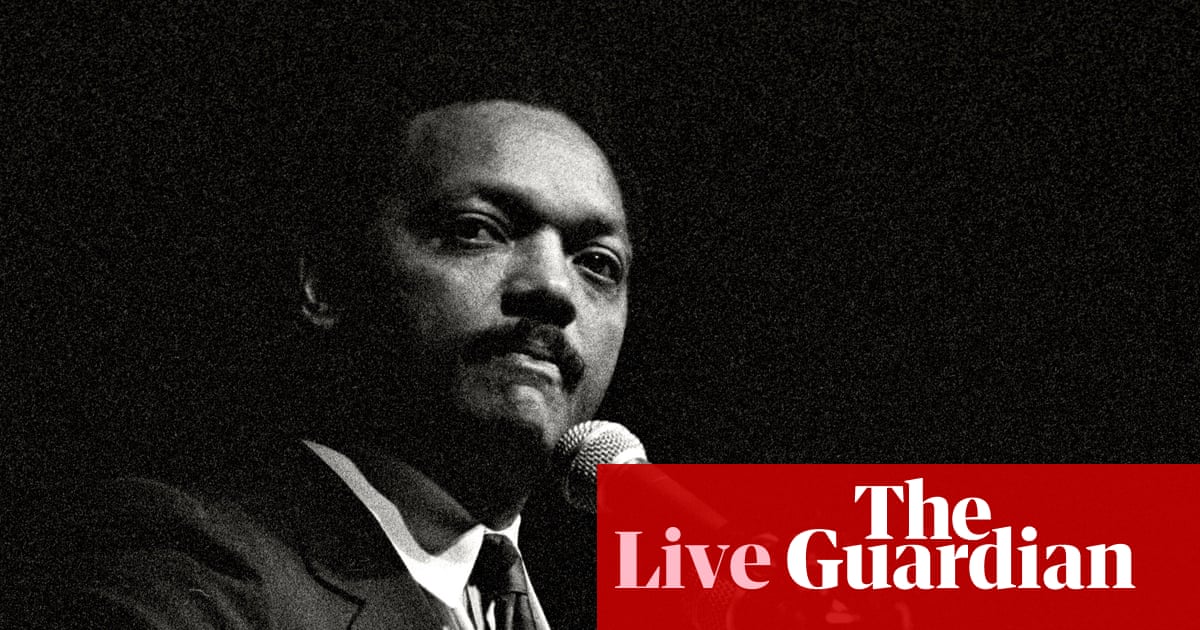

These hands-on voter registration drives were orchestrated much in part by Rev Jesse Jackson, the nationally known civil rights activist who died on Tuesday. Jackson had cut his teeth as one of Martin Luther King Jr’s youngest and most charismatic lieutenants in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and throughout the civil rights movement. By the 1970s, in the wake of King’s assassination, Jackson had transferred the movement’s master-classes in strategic organizing into founding Operation Push, a populist leftist offshoot of the SCLC that coalesced progressive whites, LGBTQ+ communities, environmentalists, Asian Americans, Indigenous Nations, Latinos, anti-war activists, and labor unions. Jackson led discussions with leadership across the country about the prospect for a national Black-backed progressive movement that could map a viable path to a Democratic nomination for president.

Like many African Americans, Jackson felt utterly betrayed by much of the Democratic party’s abandonment of socially progressive issues, democratic socialist economics, and capitulation to Reagan’s unchecked far-right neocon policies, which openly set out to undo the social and legislative gains of the Civil Rights Movement. With a bloc of 2 million new voters, however, Jackson, who earned a reputation as a Washington DC’s “shadow senator”, also knew that Black communities held the margin of victory for democratic primaries in their hands. He knew that that power could not be given away to white Democratic candidates who often made an about-face into center-right politics in their general races.

Jackson gathered a group of Black political strategists including Walter Fauntroy, a DC congressman and founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus; Rev Joseph Lowery, famed civil rights leader and SCLC co-founder; and professor Ron Walters, the noted University of Maryland political scientist to assemble the “People’s Platform,” a bulleted mandate of reforms that called for increased corporate taxes, decreased military spending, single-payer universal healthcare, and fair wage policies.

The People’s Platform did more than identify the vision for Jackson’s National Rainbow Coalition of leftist populists. For Walters, who would go on to serve as Jackson’s chief campaign adviser, it was a tactical political yardstick by which Democratic candidates could be measured in order to garner Black support. The platform strategy, which Walters explained as “dependent leverage”, set out to force white liberals into picking up the Black-backed political platform instead of putting Black support behind white Democrats and hoping to get Black demands heard.

By the fall of 1983, however, Jackson knew that dependent leverage fell short of the more immediate political force of independent leverage, which didn’t rely on awaiting concessions, but rather withheld Black support by running Black candidates who challenged white Democrat’s strongholds in the primaries. It was Jackson’s acute insight into the efficacy of independent leverage as a movement strategy that birthed his historic 1984 presidential bid.

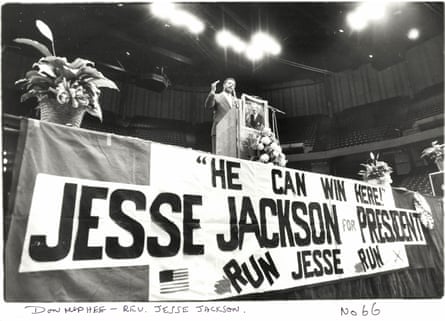

On 3 November 1983, he gathered his “rainbow” of diverse supporters into a Washington DC convention center and announced his run, becoming the first major Black candidate for president and only the second since the small, grassroots run in 1972 of Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, who joined him on stage. The announcement was riding a lightning rod of Black political momentum.

That same month, as a result of the Voting Rights Act of 1982, which protected the rights of racial and ethnic minorities to draw “majority-minority congressional districts”, the largest US cities elected a full suite of Black mayors including Chicago’s Harold Washington, Philadelphia’s Wilson Goode, Birmingham’s Richard Arrington, and Charlotte’s Harvey Gantt. Many of these party newcomers were alumni student activists of the Freedom movement who, by the 1990s, would expand Black mayoral power into Los Angeles, Atlanta, Detroit, Cleveland and Newark, eliciting the rallying cry from Jackson that “our time has come.”

Jackson envisioned his run with its electrifying “Run Jesse Run!” slogan as a front and center means to “confront liberals with liberators” and steer mainstream politics toward “the moral center of racial justice, gender equality, and peace”. He successfully shifted Black politics and leftist coalition building from the sidecar of the Democratic party and into the driver’s seat. It was Jackson’s intention to convert electoral politics into a spotlight for larger issues of Black families, inequality and economics. His flame for unapologetic progressivism was fueled by Black dissatisfaction with both Reagan and the mainstream Democrats who chased his constituents by dismissing low-income urbanites and communities of color as “special interests”.

For the Black managerial and professional class, Reagan’s opposition to affirmative action presented a direct threat to the anti-discriminatory private sector policies that had more than doubled their ranks since the 1970s. For the Black working class and unemployed, Reagan’s corrupt ushering of the crack-cocaine and mass incarceration epidemics into inner cities proved devastating alongside the obliteration of government spending on healthcare, education and job creation. Jackson took the private sphere mumblings of Black dissent from barbershops and church basements to the public podium of campaign stops and convention arenas. He shined the flashlight on party practices that sought to suppress Black votes and dilute the Black voting bloc rather than answer to it.

Confronted with Jackson’s formidable challenge, white candidates on the campaign trail downplayed their dependence on the Black vote, even when post-election analyses revealed that many white Democrats, especially in the south, had depended on as much as 90% of the Black vote in their victories. Newspaper columnists labeled Jackson an extremist, while even Black centrists like then Atlanta mayor Andrew Young warned he would spoil the race for Democratic frontrunner and former vice-president Walter Mondale who desperately needed Black primary voters in the south to defeat Senator John Glenn. These outraged reactions were only confirmation for what Jackson defiantly proclaimed in a 1984 speech: “We [Black voters] can win without the Democratic party, but the Democratic party cannot win without us.”

In a run that was far more of a moral crusade than bid for office, Jackson 84 is often misunderstood as a power grab by a charismatic camera-ready activist, or a Hillary Clinton-esque glass ceiling moment meant to put Black firsts on to the major party tickets. From the outset, however, Jackson’s chief political aspiration was to hold the party accountable to those he called “the desperate, the damned, the disinherited, the disrespected, and the despised”, who Reaganomics and the white liberals enriched by it had left to rot.

Jackson always intended to dovetail massive Black voter turnout for his run into down-ballot races for Black and leftist candidates. Cooperation up and down the ballot accomplished Jackson’s goal of exposing Democratic primary suppression of Black votes and boosted the power of Black votes in states that have held such longstanding Black blocs in congressional districts that the current Republican party cannot map a path to midterm victories without redrawing them. The momentum continued into Jackson’s second bid in 1988 (he nabbed an endorsement by Bernie Sanders, whose own presidential run would be inspired by Jackson’s model), a year after which David Dinkins was elected the first Black mayor of New York and Douglas Wilder seized the first Black gubernatorial victory in Virginia.

Mondale, who ignored adopting even the most minimal issues concerning Black voters, and did not campaign in Black communities until his last week, lost to Reagan in a landslide. Disillusioned by how Mondale had taken Black communities for granted as a “captured vote”, Walters, Jackson’s campaign manager, authored a detailed manual for the steps a Black candidate would have to take to reach the White House – 21 years before Barack Obama’s historic win, where Jackson was among thousands gathered in Grant Park, Chicago, his face flooded with tears.

When the Baptist minister strode to the Democratic national convention podium, head high, on 17 July 1984, no one expected him to be brief. After a drag-out defeat in the primaries, Jackson’s one-hour speech proved to be the high note for an otherwise uninspired convention. From the podium, the rousing orator addressed gay rights, islamophobia, and Native sovereignty, all threaded into his explanation for centering Black voting power in a fight for the party from within. “What does this large Black vote mean? Why do I fight to win second primaries and fight gerrymandering and annexation and at-large [elections],” he belted. “Why do we fight over that? Because I tell you, you cannot hold someone in the ditch unless you linger there with them.”

It is an ethos for coalition building that reverberates into today’s leftist frustrations with a Democratic party that has also been pulled center by a hard-right administration. Many on today’s left are wondering what is to be made of the recent lightning-rod momentum churned up by the democratic socialist populist campaign of New York City mayor Zohran Mamdani, and gubernatorial Democratic wins in New Jersey and Virginia. They are wondering how to hold a party accountable when it abandons its most downtrodden, expands militarism while contracting social services, and readily offers socialist policies to corporations while spurning calls for free and shared public resources from the masses.

Jackson’s strategic legacy was that no vote is captive to a party that has not earned it, and that marginalized and overlooked voters are best heard when coalitions that prioritize their common social and economic stakes challenge the party where their electoral margins for victory are the most vulnerable. Jackson’s campaign was audacious because it was never really about him as a candidate but, rather for taking the reins back on an electoral process that wanted Black votes without including Black people.

It was a rebellion masked as a campaign. As the Harvard political theorist Brandon Terry wrote, “Jackson’s campaigns were, at bottom, a remarkable attempt to merge symbolic and structural politics … His campaign helped refound a Democratic party whose internal corruptions and hierarchies had been the target of civil rights activism. That blend of charisma and concrete party reform is all-too-rare in American history. ” Forty-one years later, “Run Jesse Run” hasn’t run out of relevance for how those who have been historically deprived of the most power can move swiftly to reclaim it.

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3