On 8 October 1969, a band of guerrillas disguised as mourners in a funeral procession marched into the small Uruguayan town of Pando. They took over the police station, the town hall and the telephone exchange, then robbed several banks, before being confronted by the armed forces and driven out. Five people were killed, including a civilian.

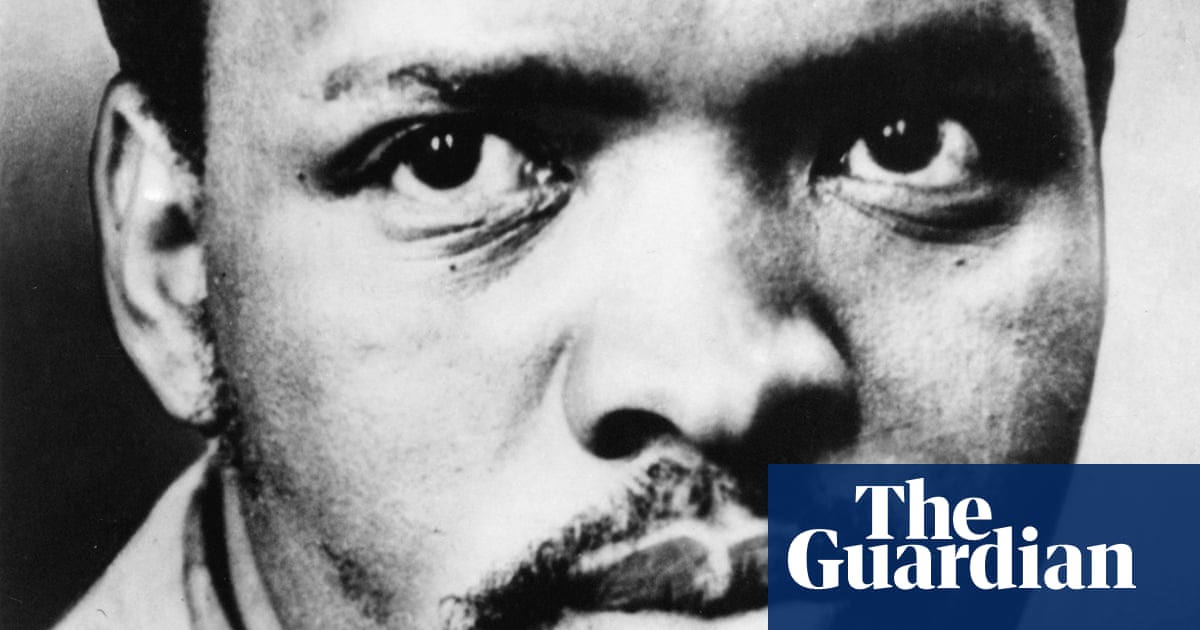

One of the leaders of the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional–Tupamaros guerrilla group that day was José Mujica, who 40 years later became president of Uruguay. Mujica, who has died aged 89, distinguished himself from many politicians by donating 90% of his presidential salary to charity, and for continuing to live on his smallholding outside the capital, driving to the presidential palace in an old VW Beetle. Called El Pepe by most Uruguyans, he was widely known as “the poorest president in the world”. In later life he won a wide following among young Latin Americans who admired his progressive principles and simple life.

However, for some years in the late 1960s and early 70s, Mujica and the other Tupamaro urban guerrillas shook the foundations of the Uruguayan state, one of the most firmly established parliamentary democracies in Latin America.

The Tupamaros aimed to bring in a revolutionary socialist government such as the one they had seen triumph under Fidel Castro in Cuba a decade earlier. They specialised in spectacular actions such as the storming of Pando, blowing up foreign firms and kidnapping high-profile businessmen and others, including the British ambassador to Uruguay, Geoffrey Jackson, who was held captive for eight months in 1971 until he was released after Edward Heath’s government agreed to pay his ransom.

In March 1970, Mujica was shot six times while resisting arrest in a Montevideo bar, but escaped, only to be captured and imprisoned later that same year. In 1971, he was one of more than a hundred guerrillas to escape from Punta Carretas prison by digging a tunnel out into a nearby house.

After being arrested and escaping several times, in late 1972 he was detained and imprisoned without trial. By now the turmoil spread by the Tupamaros and other groups was so great that the Uruguayan military seized power in a coup. For the next 12 years, Mujica and eight other Tupamaro leaders were held as hostages, often in terrible conditions. Mujica was kept in solitary confinement for long stretches, with no access to visitors or books.

He survived, and with the end of the military dictatorship in 1985 benefited from an amnesty for political activists judged not to have been directly responsible for any deaths. He was one of the founders of the leftwing Movimiento de Participación Popular (MPP), which became a main partner in the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) movement that sought to take power by peaceful political means.

In 2005, the Frente Amplio succeeded for the first time in winning the presidency as well as a majority in the national parliament. Mujica was appointed minister for agriculture. In the same year he married his long-term partner and political comrade Lucía Topolansky.

Mujica became the Frente Amplio’s presidential candidate in the following elections, and took office on 1 March 2010. During his presidency, Uruguay adopted many progressive laws, including the legalisation of abortion, same-sex marriage, and the production and sale of marijuana. Further legislation strengthened the role of trade unions, and the minimum wage was increased significantly. He also welcomed hundreds of refugees from Assad’s Syria to Uruguay, arguing that, as with his family, Uruguay was a country of immigrants.

Born in Paso de la Arena near the capital, Montevideo, he was the son of Demetrio Mujica, a farmer whose ancestors came to Uruguay from the Basque Country in the mid-19th century, and Lucy Cordano, of Italian descent. After the death of his father when José was only four, he helped on the family farm and went to local schools.

By the mid-60s he had become a follower of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, believing only revolutionary change could solve his country’s social and economic problems, and joined the Tupamaros.

As president, while not reneging on his revolutionary past, Mujica stressed he was a pragmatist who had to operate within the established system: “I need capitalism to work, because I have to levy taxes and attend to the serious problems we have,” he told journalists.

Since the Uruguayan constitution does not permit a second consecutive term in office, in March 2015 Mujica withdrew to his property on the edge of Montevideo, where he set up an agricultural education centre.

He continued to be active in politics as a national senator until 2018 (the year a film about his life, El Pepe, Una Vida Suprema, came out), and in talks and on social media, where his radical idealism found a new young audience.

“Life is a beautiful adventure and a miracle,” he said. “We are too focused on wealth and not on happiness. We are focused only on doing things and, before you know it, life has passed you by.”

He is survived by Lucía.

3 months ago

131

3 months ago

131