Spirit of Place is a collection of minor travel pieces published by Lawrence Durrell in 1969. “Spirit of Place”, though, could easily serve as a descriptor for the entire arc of Durrell’s literary output: Prospero’s Cell (1945), an account of three years spent on Corfu before the second world war, the Cypriot memoir Bitter Lemons (1957), and the career-making Alexandria Quartet (1957-60). The islands and littorals of the Mediterranean gave Durrell his subject, remade by him into a theatre in which men and women, displaced by the political and social violence of the mid-20th century, stumbled towards each other amid the ruins of ancient civilisations.

It feels right, then, that this biography of Lawrence Durrell, only the second major one since his death in 1990, is by Michael Haag, who spent his career writing about the eastern Mediterranean. Haag’s best book was Alexandria: City of Memory (2004), which drew on the writings of Cavafy, EM Forster and Durrell to reconstruct the polyglot culture of the Greek, Italian, Jewish and Arabic population that flourished for centuries on the shores of north Africa. By the time of his own death in 2020, Haag had completed this biography of Durrell up to the year 1945, and the decision was made to publish posthumously. The result reads like an abbreviated account of Durrell’s life rather than an amputation: despite not becoming a significant literary figure until 1957, most of Durrell’s formative experiences had taken place by the time he left the city at the end of the war.

Haag’s insistence on treating place not just as a matter of landscape but also as social nexus provides new insights into Durrell’s earliest years. The standard version has always been that his family was Anglo-Indian, with parents who were ethnic Britons living and working during the Raj while longing continually for “home”. Lawrence Durrell Sr was even that quintessential figure, a civil engineer, at work on the railways that were joining up the subcontinent. Yet Haag’s forensic analysis reveals that the Durrell family was located very far down colonial India’s pecking order. Both Lawrence Sr and his wife, Louisa Dixie, were “country born” in the Punjab, with only tenuous connections to Britain. On Louisa’s side there may have been Indian blood. The decision not to automatically send the four surviving Durrell children back to “Blighty” (a corrupted Urdu word) for their education likewise marked the family out as being perilously close to the Eurasians who made up colonial India’s subaltern class.

Haag is also able to put to rest some of Durrell’s more outrageous fibs. It is not true that his family was Irish – he probably just liked the way it made him seem not-English. Nor, in his boarding school in Darjeeling, could young Larry see Everest from the foot of his bed: the windows of his dormitory looked out on to dreary playing fields. Such misdirections were perhaps an attempt to disguise a childhood that was distinctly troubled. Louisa – “Mother” in My Family and Other Animals (1956), by younger brother Gerry – had already started her descent into full-blown alcoholism, an addiction she passed on to all three of her sons.

Haag has dealt before with the Corfu idyll in The Durrells of Corfu (2017), but in this retelling he reminds us that even in Eden things were not always as they seemed. On the island, the Durrells were socially suspect: the gentry class found them rough and boorish, while the priests and peasants were deeply offended by their insistence on swimming in the nude without worrying who saw them.

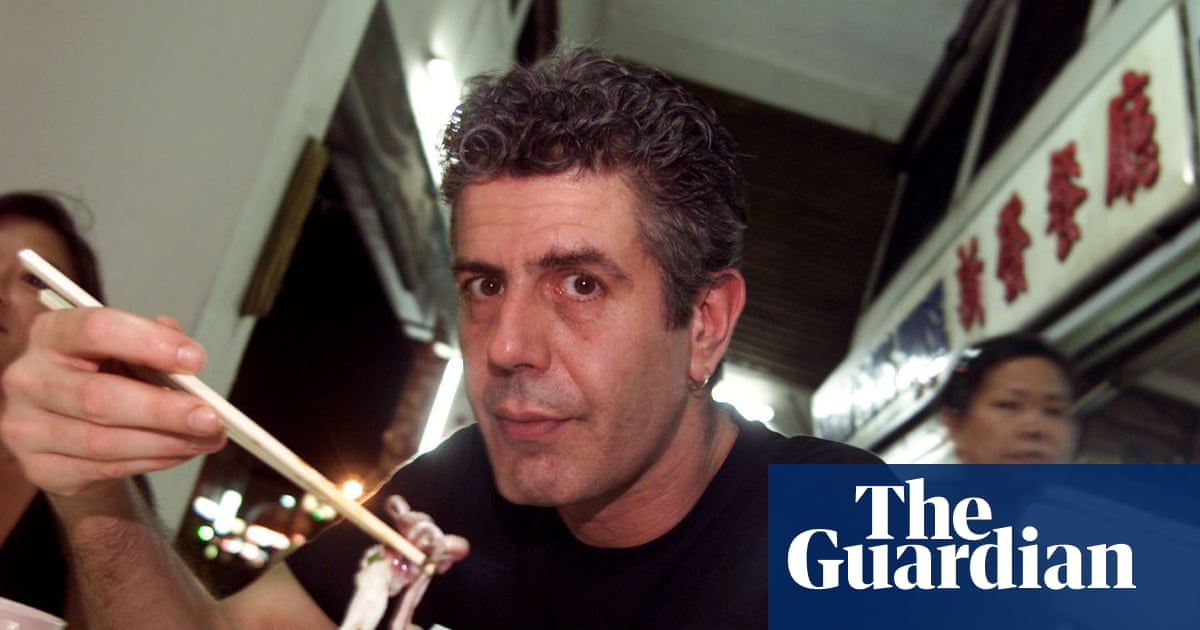

This biography inevitably comes into its own once Larry touches down in Alexandria in 1942 as the newly appointed press attache to the British embassy. Haag’s descriptions of the city’s melting-pot culture and its steamy eroticism are wonderfully done. It was here that Larry met Eve Cohen, the model for Justine in the first volume of The Alexandria Quartet, who became his second wife.

Durrell’s previous biographer Ian MacNiven was in the tricky position of having been invited by his subject to write the book, for which he would be given access to private papers. The result was both overlong and overawed. Haag doesn’t set out to do a hatchet job, but he is clearer on Durrell’s dark side. The puckish author, no more than 5ft 4in tall, was free with his fists, snobbish and racist (Eve’s Jewishness seemed both to intrigue and repel him). The book’s cut-off point of 1945 means that later accusations by Durrell’s daughter Sappho that he compelled her into an incestuous relationship are not explored. She killed herself at the age of 33.

Missing, too, is any assessment of where Lawrence Durrell’s literary reputation currently stands. In truth, he is not much read or liked now, his books coming over as bloated and cod-metaphysical in a way no amount of gorgeous phrase-making can quite redeem. Durrell’s time may come again, but at this point we will have to be satisfied with Haag’s account of him as a supreme writer of place, rather than as an astute investigator of the human condition or, even less persuasively, an overlooked modernist master.

3 months ago

51

3 months ago

51