‘We didn’t want to be the cops,” says Bobby Weir, guitarist and founder member of the Grateful Dead, laughing as he describes his band’s legendarily lax attitude to people taping their concerts. Bootleggers were given their own area at gigs on the proviso their tapes were traded, not sold – an illustration of the band’s generosity of spirit. “It was an easy decision to make,” Weir says.

Decisions like those have ensured that, decades before today’s obsessional Swifties and K-pop stans, the Dead have cultivated one of music’s most passionate fandoms. They are surely the world’s best-documented band. This year, they’re marking their 60th anniversary with a 60-CD box set, just one of many gargantuan packages over the years. Their 2024 Friend of the Devils box set only covered a single month of live music (April 1978) yet it stretched to 19 CDs.

“When we first got started,” says Weir, “it quickly became apparent that the business of music was pretty much populated by people who were only a notch above – or maybe not even a notch above – the level of professional wrestling. The business was really tawdry. And so we went about things in our own way.”

The Dead have duly operated largely outside the mainstream: not so much a band as a fiercely independent travelling circus that could comfortably sell out 100,000-capacity stadiums, while only ever having had one single grace the US Top 40 (Touch of Grey in 1987). While the original lineup ended in 1995, with the death of bandleader Jerry Garcia, a plethora of Dead-related projects have spiralled out ever since.

In June, Weir’s band Wolf Bros will play the Royal Albert Hall in London, alongside a full orchestra. Meanwhile, the wildly successful spin-off band Dead & Company has just finished a residency at the Las Vegas Sphere, the immense dome that dominates the strip skyline. Formed in 2015, the lineup includes 77-year-old Weir on guitar and vocals, with original drummer Mickey Hart and various guests. Dead & Company are big business: their 2023 tour grossed $115m, not far behind Metallica, Depeche Mode and Coldplay.

The Vegas show featured a mind-bending AV element. “For us,” says Weir, “it’s a matter of what are the storytelling possibilities on stage?” He adds that in the 1960s, “we’d do liquid light shows. It’s a part of what we do, always has been.”

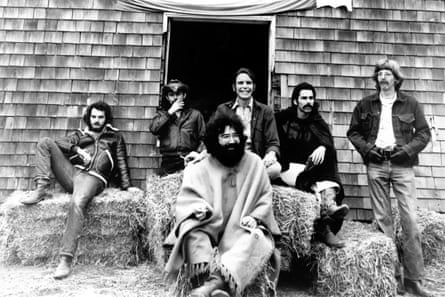

Emerging from the San Francisco Bay Area’s countercultural maelstrom in 1965, the Dead gained a reputation for hypnotic, freewheeling, improvised jam sessions. No two gigs were ever the same. Psychedelic in their sheer unrelenting scope, yet grounded in a rootsy, bluesy Americana, theirs was music you could move to. It was the time of Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests – LSD advocacy parties with a rotating lineup of acts at the author’s farm at La Honda, California. These provided a natural setting, though today Weir is surprisingly loth to attribute too much importance to chemical influence.

“I don’t think drugs had all that much to do with our development, actually,” he says. “I was in and out of that scene. But after a year or so of taking LSD, I felt it just wasn’t bringing me much in the way of clarity or new direction. So I stepped out of it. Some of the guys smoked pot for decades but I don’t think you’d find – certainly with what’s going on in Dead & Company – that there’s much in the way of drug use. We’ve really been there and done that.”

As the Dead’s popularity grew, a significant number of their fans – known as the Deadheads – began dedicating their entire existence to the band, planning their lives around tours, where they would set up food stalls or sell clothes to support a full-time nomadic lifestyle.

John Kilbride, author of The Golden Road: The Recorded History of the Grateful Dead, recalls “going down the Barras market in Glasgow in the early 80s and getting a load of live cassettes, and just being completely spun around by the sound. Even some of the more underground bands in the UK were nowhere near as radical from a business perspective, encouraging fans to tape shows and so on. Not even Hawkwind did that!”

It didn’t stop at taping: the Dead set up publishing companies and record labels, booked their own gigs and tried to keep everything DIY. The back cover of 1971’s Skull and Roses live album bore the promise: “Tell us who you are … we’ll keep you informed.” By the 1980s, the Dead boasted a mailing list of over half a million fans, and were also frequently handling their own ticket distribution – no mean feat when it came to stadium shows.

The full Dead experience was, to many fans’ ears, never captured on a studio recording. “I mean, we got some of it down,” says Weir. “American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead fell together pretty well. But I won’t say they reached some of the loftier moments that we got to on stage. In order to really get what we’re doing, and what we’re up to, you’ve got to be there.”

Weir uses the extremely Dead-coded phrase “gestalt linkage” to describe the quasi-telepathic feeling that has resulted from more than half a century of playing. “That’s what we bring to the table,” he says, “although it’s not all that unusual: a good jazz band will have that going. We’ve learned to trust each other. That makes a big difference.” The linkage wasn’t even broken by Garcia’s death, aged 53. “The feeling that we had to carry it on was immediate,” says Weir. “Jerry wouldn’t have had it any other way. It was a major blow to us for sure, but there was no fighting it, so on we went.”

But how have they kept such passionate fans onside for six decades? Sam Bedford, co-founder of Brighton record label None More Records, is one, and he emphasises a lack of polish and predictability. “They were different to everyone else,” he says, “and yet they couldn’t find stadiums that were big enough.” He marvels at how they’d play “10 minutes of feedback during the 60s, or in the 80s, doing 20-minute ambient interludes. It’s incredible that they were playing to 90,000 people and there’s an ambient interlude in the middle. I love all that stuff!”

I wonder if there are tensions between the countercultural, DIY, rootsy aspects of the band, and a project such as the Las Vegas Sphere residency. “The Dead have always been a broad church,” Kilbride argues. “There’s people who want to go to a big slick show and spend hundreds of dollars on merchandise, but they had that element in the 70s, too. The well-heeled fans who would jump on a plane to shows and stay in the same hotels as the band – that’s always been there. So have the people who’ve spent hundreds of miles on the road and make a living selling T-shirts. It works on every level and there’s space for both.”

Part of the ongoing attraction is that, even today, the band don’t just trot out a steady setlist of classics. Kilbride has just bought a ticket to see Weir and Wolf Bros at the Royal Albert Hall in June. Even as a diehard fan, he says: “I have no idea what to expect.”

The London gig will feature two sets: Dead classics and music from Weir’s solo repertoire, all with the orchestra. “We’ve been hearing enormous philharmonic renditions of what we do all along,” says Weir. “That’s what’s been going on in our heads – it’s been great to be able to flesh that out.”

Bassist Phil Lesh died in 2024 and it’s not clear how long the Grateful Dead’s legacy can last after they stop playing shows, without a definitive run of studio albums. But Weir says that isn’t really the point of the band: “We initially learned to play from a place of profound disorientation and fun – where we didn’t have much legacy to draw from, when we were playing at the Acid Tests and that stuff. Every time we pick up our instruments, it’s a new situation.”

1 month ago

28

1 month ago

28