As a veteran of the crisis management business, Eric Dezenhall knows a thing or two about the murkier parts of politics. As the author of Wiseguys and the White House: Gangsters, Presidents and the Deals They Made, he knows a lot about the shady places where power and organized crime collide. A survey of presidents from Franklin Roosevelt to Joe Biden and their brushes with the bosses, Dezenhall’s new book will be published a week shy of Donald Trump’s second inauguration.

According to Dezenhall, “the thing that makes Trump different from all of the other presidents is he’s the only one who has been shockingly open about talking about” his experiences with the mob.

“To him, it’s a branding thing. Everybody else is running from the mob context. Trump, he’s on Letterman, telling you he knows them. And not only does the public not punish him for it, they elected him twice. They’re fine with it. And yet the idea that somebody would run for office using mafia connections as part of their branding is really something to behold.”

In 2013, Trump appeared on the Late Show. The host, David Letterman, asked: “Have you ever knowingly done business with organized crime?”

Trump said he had “really tried to stay away from them as much as possible”, though “growing up in New York and doing business in New York, I would say there might have been one of those characters along the way”.

Then he said: “I have met on occasion a few of those people. They happen to be very nice people.”

Even then, years before Trump entered politics, it seemed an odd thing to say about men who trade in extortion and violence. But as pictorial evidence of Trump’s mob adjacency abounds – in two days in 2023, shots surfaced of him with Joseph “Skinny Joey” Merlino, a Philadelphian twice imprisoned, and John Alite, a former hitman for the New York Gambino family, jailed for robbery and murder – so Trump’s remarks to Letterman pointed to the facts of his business career.

Dezenhall says: “One of the things Trump says that drives people crazy is whenever he’s accused of something untoward, he says, ‘That just makes me smart.’ I reluctantly concede that in this case he may be right.

“Picture a tower being constructed in Manhattan. You probably picture a steel skeleton and a crane. You don’t picture concrete, but that’s what Trump used. Steel is not centrally controlled. It’s an international industry. Concrete is controlled locally. And in New York at the time he built Trump Tower, only two companies did it, and they were owned by the Genovese, Gambino and Colombo families. And so what did Trump do? He got a good contract.

“A prosecutor friend of mine said, ‘If you could prove that he got something in return …’ I said, ‘Stop saying that. It was almost a half-century ago. No one’s proven anything.’”

Dezenhall grew up across the river in New Jersey, home to real and fictional bosses from Nucky Johnson to Tony Soprano, the state where Trump built (and lost) a casino. The first book Dezenhall remembers buying, aged 10, was about the American presidents. After a career in and around politics that began with a spell in Ronald Reagan’s White House, two abiding interests have come together.

He once “asked an uncle, this must have been 30 to 40 years ago, ‘What’s with Trump and the mob in Atlantic City? You hear that. But what does it mean?’ And my uncle said, ‘This is very simple. He overpays for real estate, and that’s how he gets labor support.’ So it’s in the book.

“You know the Bruce Springsteen song, Atlantic City? ‘They blew up the Chicken Man in Philly last night.’ Well, the Chicken Man was Phil Testa” – a Philadelphia mob boss killed by a nail bomb in 1981 – “and in Atlantic City, Testa’s son, Salvie Testa, sold Trump a crummy piece of property that was worth $195,000 and Trump paid $1.1m, and he did it through a secretary, and he got this piece of property, which I think they used as a parking lot or something for his casino. And Trump’s detractors would say that’s how he compensated for labor peace. All Trump has said is something to the extent of, ‘Hey, you know, sometimes I get the right price, sometimes I don’t get the right price. Where’s the crime?’

“And here we are, 45 years later, and no one’s proven anything. And so when he says, ‘That makes me smart,’ let’s bite our lip and say he might be right.”

Dezenhall’s chapter on Trump also considers his fondness for dressing and acting like a New York don and even a rumored offer to be an FBI informant, a common gambit among capos and killers. Unsurprisingly, Trump is among the presidents Dezenhall considers to have brushed closest to the mob, though the only commander-in-chief to score top marks on Dezenhall’s one-to-five scale for such ties is Harry Truman.

“That’ll surprise people,” Dezenhall says. “I’m a Truman fan, I’ve read a lot of the biographies, and what fascinated me is the Mafia is hardly mentioned at all. The machine stuff” – Truman’s origins in Democratic politics in Kansas City – “is mentioned, but not the fact that this was a mafia-slash-Cosa-Nostra-controlled machine, to the point where people would call the police and a mobster would answer the phone and decide whether to dispatch a squad car, if they didn’t want the cops busting up a gambling joint.”

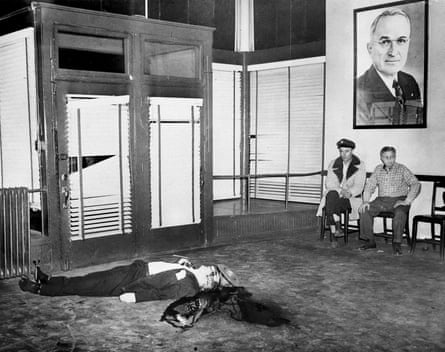

Wiseguys and the White House reprints an extraordinary picture, the gangster Charles Gargotta lying dead in a pool of blood in a Democratic Club in Kansas City, under a portrait of Truman. It happened in 1950, when Truman was president.

To Dezenhall, “Truman is interesting in the sense that he he didn’t openly talk about it very much, but he kind of had this grudging attitude: ‘Look, I’m not happy, but in order to do what I need to do, I can’t avoid these people.’ And what does it say that the mob chose a person to be president who was the same president who dropped the [atomic] bomb? That’s some heady stuff.”

So are more familiar tales, of John F Kennedy having the same girlfriend as Sam Giancana from Chicago, or of mob involvement in attempts to kill Fidel Castro, under JFK. Dezenhall dismisses the old line that the mob killed Kennedy – “My running joke is with Kennedy stuff, no conspiracy theory, no book contract” – but gives more credence to the equally startling story of how the Roosevelt administration deployed mobsters to watch the docks for Nazi saboteurs, then to help prepare the invasion of Sicily.

Very often, Dezenhall concludes, presidential proximity to organized crime is simply unavoidable, because of the intertwined nature of politics, the mob, labor unions, city and state party machines and other powerful interests. Most often, presidents are unaware of the precise nature of such ties. Many, Kennedy and Richard Nixon prominent among them, oversee crackdowns on organized crime at the same time as flirting with it.

Dezenhall’s book contains a profusion of fascinating stories. Lyndon Johnson, for example, most likely didn’t know that his order to FBI director J Edgar Hoover to do anything necessary to find three civil rights workers murdered in Mississippi in 1964 resulted in the FBI deploying Greg Scarpa, a psychopathic mob killer, to extract information from the Ku Klux Klan.

Reagan, meanwhile, had links to Sidney Korshak, a lawyer with mob clients, and owed a lot to Lew Wasserman, a Hollywood agent who also had mob ties.

“Old friends aren’t thrilled with me,” about the Reagan chapter, Dezenhall says with a laugh. “But one of the things I have prosecutors tell me, which is in the book, is that while Reagan went after the Mafia hard as president, he did not go after Lou Wasserman and Sidney Korshak. Those investigations were killed.”

Dezenhall’s final chapter concerns Joe Biden, who only scores one out of five on the mob adjacency scale. Nonetheless, Dezenhall tells a remarkable story from 50 years ago. It involves the Democratic machine in Delaware, where Biden ran for US Senate at 29, and its use of a union official with mob ties: none other than Frank Sheeran, the Teamsters enforcer played by Robert De Niro in The Irishman, directed by Martin Scorsese.

Biden “was a kid, running for Senate against a powerful incumbent”, Dezenhall says. “And the incumbent prepared these really strong newspaper ads against Biden.” Without Biden knowing, Sheeran made a simple but effective intervention. “He made sure the newspapers weren’t distributed.

“That’s an example of a conspiracy that really works. What doesn’t work is 300 people get together to kill Kennedy. No, didn’t happen. The papers not getting picked up? Certainly did happen.”

-

Wiseguys and the White House is out on 14 January

3 months ago

75

3 months ago

75