Events in the United States of Trumpland continue to reveal staggering new dimensions to the possibilities of orchestral music. Trump’s announcement that his “Trump Kennedy Center” is to be shut for a refit is a brilliantly cynical way to stop the noise when artists try to cancel their appearances during the rest of his presidential tenure: it’s shut already! Bigly losers, all of you!

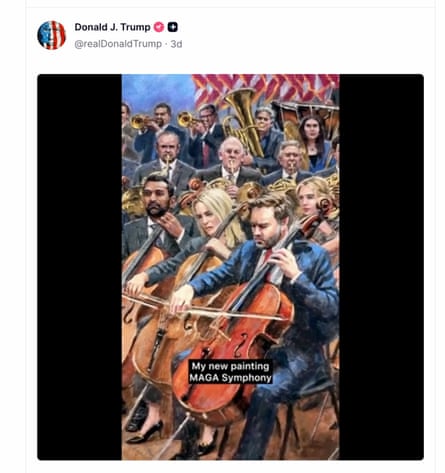

But that’s not the new dawn for the artform I’m talking about. I mean the inspirational painting unveiled by the maestro of Trumpian kitsch, Jon McNaughton (and stamped with the presidential seal of approval – ie a post on Truth Social).

Maga Symphony depicts Trump as a conductor of the politicians and cultural figures who are Making the Orchestra Great Again. Who’s in this Maga fever dream of an orchestra? Marco Rubio leads the violins, JD Vance takes the cellos (Melania is relegated to the second desk), his sons and Roger Stone are on double basses, the foundation of the orchestra’s ideological soundworld. A bizarrely configured woodwind and brass lineup features four flutes and no oboes – mind you, there are no violas either, those shape-shifting probable Democrats! – plus Tom Homan on horn, with Tucker Carlson cheerleading on the cymbals. Where’s Elon Musk, you ask? On electric guitar, of course: the joker in the orchestral pack.

As McNaughton describes this image, “you can feel it – the music is coming together – rising and stirring something deep inside … When Americans pull together and trust a shared vision, they create something strong, lasting, and bigger than any one person.”

And that’s the cultural trope that this ludicrous image burnishes: the idea of the all-powerful conductor, inspiring total command and obedience from his musicians, which has been inspirational catnip for dictators from Hitler to Stalin to Mussolini. As Elias Canetti wrote in his book Crowds and Power: “There is no more obvious expression of power than the performance of a conductor … He has the power of life and death over the voices of the instruments.”

Orchestras can represent an ideal society – if, that is, you’re a wannabe despot. Imagine: one hundred musicians, working in perfect togetherness to realise your vision, with no possibility of dissent, criticism or disagreement. Every tiny movement of your arms and facial expressions is magicked through the force of pure will into the sounds of your deepest desires. Which self-respecting autocrat wouldn’t want that kind of social control?

McNaughton’s Maga orchestra takes the idea a stage further. There are no music stands in front of the players – they are performing through Trumpian telepathy, a connection as mystical as it’s musical. It’s not so much a Maga symphony as a political seance turned into sound.

This concept of the orchestra didn’t only take hold of the fevered imaginations of dictators in the 1930s and presidents in the 2020s. Works such as McNaughton’s are routinely used in less obviously politically inflamed contexts to describe the potential social good that orchestras can do, from apologists for Venezuela’s El Sistema – its “system” of music education, and its satellites all over the world – to many leaders of orchestral culture here in the UK. If society worked more like orchestras, the story goes, our lives would all be better, because in orchestras everyone’s giving up their individuality for the greater good.

But that’s a deeply problematic idea, because orchestras never work in absolute harmony. An orchestra is created through the tensions between the individual wills of the players and their contribution to the collective. The best orchestras do not function like well-oiled machines, drilled to the finest margins of unanimity. Instead, they’re models of a controlled chaos of human emotions, desires and virtuosities that are held in tension, balance and friction in the moment of performance. They’re made from the transfigured experience of listening to each other. When orchestras really fly, the conductor isn’t an all-powerful musical despot, instead, he or she is an inspirer of a dynamic culture in which everyone responds to where the musical discourse is going, recognising when they’ve got the tune or the accompaniment, creating a permanent state of flux, volatility, and creative negotiation.

The Trump image is comic, and troubling, because it reinstates the idea of the relationship between conductors and orchestras as populist shorthands for autocracy and demagoguery. No doubt the Association of British Orchestras’ annual conference, convening in London this week, will inspire a more genuinely collective vision for the future of the orchestra in this country. Or maybe an enterprisingly craven orchestra will sign up Trump as their next music director. Stranger things have happened. And probably will by next week.

This week Tom has been listening to: Kevin Puts’s Emily: No Prisoner Be, Joyce DiDonato’s collaboration with Time for Three. It is communicative and urgently powerful in recording and performance. (Apple Classical | Spotify)

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2