Markets are braced for another rollercoaster week as the most punitive of Donald Trump’s tariffs kick in and world leaders weigh up retaliatory action, adding to fears of a global recession.

Stock indices plunged by nearly $5tn (£3.9tn) last week, with markets in the UK and US experiencing losses not seen since the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, as investors took cover from the opening salvoes of Trump’s trade war.

With no sign of the Trump administration rowing back on its so-called “liberation day” tariffs, analysts warned of persistent market turbulence and an increased risk of all-out recession in the US, UK and EU.

Roman Ziruk, a senior market analyst at the global financial services firm Ebury, said: “Volatility will likely stay elevated as we move into [the] week.”

He said some investors were still holding out hope that tariffs against China and the EU, due to kick in from Wednesday, would be delayed or remodelled.

“The danger of escalation of trade tensions cannot, however, be overlooked, particularly as China’s response to the latest round of US tariffs has been more aggressive than before,” Ziruk said.

However, leading figures in the Trump administration warned on Sunday against expectations for a U-turn. Speaking in television interviews, Howard Lutnick, the commerce secretary, said the US president intended to “reset global trade”.

EU leaders are still considering their response, while Keir Starmer, the UK prime minister, has vowed to “shelter” British businesses from the impact of tariffs, indicating he will announce what steps he plans to take this coming week.

Starmer is expected to pursue an economic reset, which could ultimately include a rethink of Labour’s promise not to raises taxes, in anticipation of a global trade slowdown.

On Sunday, the Treasury minister Darren Jones told the BBC that the era of globalisation has “come to an end”, although he said the UK was still hopeful of striking a trade deal with the White House.

The 10% rate imposed on the UK is at the lowest end of the range of Trump’s tariffs, with the exceptions of Russia, North Korea, Belarus and Cuba, which were left out of the worldwide trade dispute altogether.

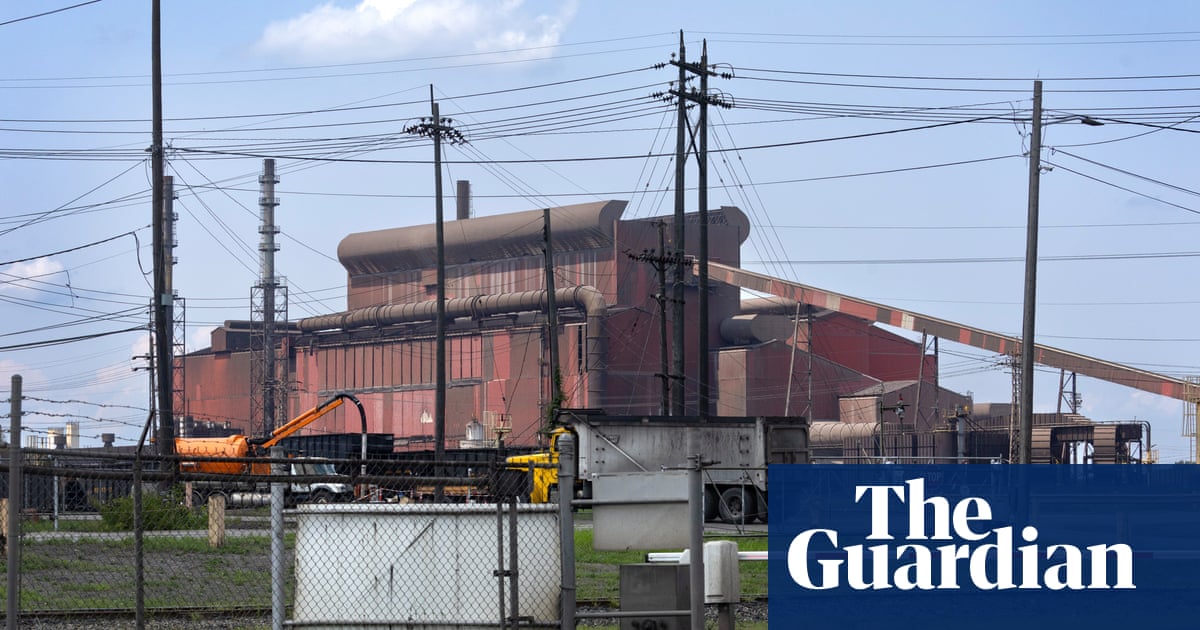

But Trump had already imposed a 25% tariff on UK steel and cars, a measure that prompted Jaguar Land Rover to say over the weekend that it was pausing shipments to the US, which buys about a quarter of the 400,000 vehicles the company sells annually.

Economic forecasters said the unexpectedly widespread and punitive nature of the tariffs could still tip the UK economy into decline.

Analysts at Barclays said the UK and EU were at risk of falling into recession in the second half of this year and they revised down their growth forecasts for both economies, as well as for the US.

Erik F Nielsen, the chief economics adviser at UniCredit Bank, said: “It’s too early to estimate the impact of these economic weapons of mass destruction.

“But it’ll be bad – very bad – for US growth, and for growth across the rest of the world. A recession in the US, maybe even a global recession, have become distinct possibilities.”

after newsletter promotion

On Saturday, the world’s richest person, Elon Musk, who has emerged as Trump’s most powerful ally in global business world, told a meeting of Italy’s rightwing League party that he hoped a “free-trade zone” between the EU and US could be created, with no tariffs at all.

But duties of 20% on European imports to the US technically take effect at one minute past midnight on Wednesday, as does the 34% rate for China, the world’s biggest export nation, and others deemed by the White House to be among the “worst offenders”, which includes Japan and Vietnam.

Leaders of European countries have condemned the tariffs, while the French president, Emmanuel Macron, appeared to call on the country’s businesses to halt investment in the US.

The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, has called for negotiation with the US. However, the EU is expected to announce retaliatory tariffs on US consumer and industrial goods – which are likely to include emblematic products such as orange juice, denim and Harley-Davidson motorbikes – in mid-April as a response to steel and aluminium tariffs previously announced by Trump.

While Beijing has already responded with retaliatory tariffs, George Magnus, an expert on China’s economy, said a deal in the longer term was still possible.

“Neither Trump nor [the Chinese president] Xi Jinping want a full-blown trade war right now,” said Magnus, who is the former chief economist at the Swiss bank UBS and a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre and Soas University of London.

“Trump needs to show voters that the use of tariffs for revenues and leverage is working without putting the American economy through a damaging slowdown or recession,” he said.

“Xi has his own deep-seated economic problems […] without having to manage a harmful external trade war. A big hit to exports would have profound consequences for growth and employment.”

However, he warned of the long-term implications of Trump trying to loosen China’s hold on global supply chains, while Beijing continues trying to boost exports.

“The world must either pay Trump now via tariffs, or pay Xi Jinping later through lost manufacturing and jobs,” he said.

2 days ago

10

2 days ago

10