‘Even when humans get serious about wanting to talk to dolphins, will dolphins have anything to say to us?” So pondered an issue of Esquire magazine in 1975. “The only reliable way to find out,” it concluded, “will be to build a Dolphin Embassy and look for the response.”

The pages that followed were devoted to a fantastical vision, created by the avant-garde architecture collective, Ant Farm. They proposed a floating multi-species utopia where humans and dolphins could mingle in a watery fantasy, communicating through telepathy. The triangular vessel featured a land-water living room, with chutes enabling dolphins to swim between floors, as well as a shared navigation pod, where one day an “electronic-fluidic interface” would allow both humans and dolphins to steer the ship. The hope was that technological advances would make the project buildable by the 1990s. “Thus far,” the article noted, “no backers have come forward.”

Fifty years on, there is still no delphinid mission, but Ant Farm’s acid-induced drawings are on display in the Design Museum, as part of an exhibition about current designers’ attempts to work with and for the “more than human” world. Today’s young architects might no longer be communing with their animal clients through psychedelics (alas!), but a whole new generation is engaging with the natural world once again, in the realisation that it’s not enough to mitigate the human impact on the planet: we must actively design for other species to flourish.

The resulting show is an intriguing, if sometimes opaque, foray into numerous experiments and “collaborations” with nature, from fungal facades to fabrics grown from grass roots. Some are realistic proposals that have been put into action, while (too many) others occupy the realms of fantasy or conceptual art. But a good deal of exhibits will make you think again, and contemplate your relationship with everything from spiders and seaweed, to wasps and worms.

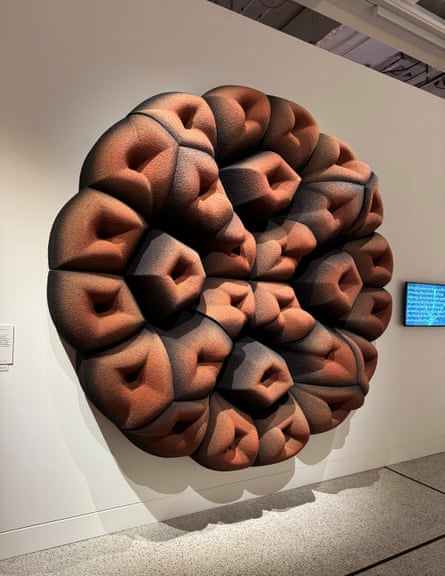

Architect Andrés Jaque, who recently sprayed a school in Spain with a globular coating of insect and fungi-friendly cork, is back with an even more wildlife-welcoming facade. His “transspecies rosette”, a sample of a new cladding system made of pulverised cork and natural resin, features deep clefts and niches to encourage life to take hold, while providing waterproof insulation for the building. Modernism might have led to a wipe-clean world of sleek, seamless surfaces (all that high-rise glass resulting in accidental bird massacres), but Jaque’s work suggests that more-than-human-centric design could lead to much more interesting, knobbly kinds of architecture. Does a bio-gothic future await?

Nearby, Kate Orff of landscape architecture firm Scape, presents her more pragmatic Bird-Safe Building Guidelines, showing how the differences between human and avian vision could be turned to advantage. By applying films, glass can be made to look opaque to birds, while remaining transparent to humans. This simple measure could save a billion bird deaths a year, in the US alone.

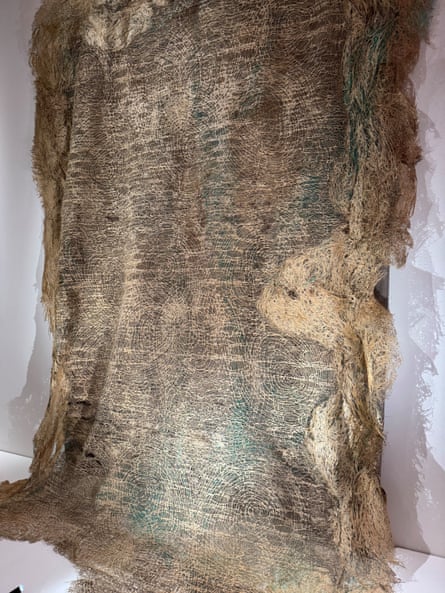

There are a handful of practical solutions like this scattered throughout the exhibition, but at several points in the show you feel like reminding the curators their remit is design, not art. There are a few too many space-filling installations, like Julia Lohmann’s Kelp Council, which looks like a series of couture dresses fashioned from seaweed, dangling in a circle, set to a bubbling backdrop of oceanic sounds.

“If we consider that all living things have their own needs and agency,” offers a caption, “we might ask: what does seaweed think of us?”

Quoth the kelp: “Do better.”

Other projects seem promising, until you realise they have yet to be tested in the real world. There is a reason so many designers gravitate towards the ethereal realms of installation art and “research”, of the kind that now fills biennales: it’s a lot easier to comment on a problem than solve it.

The seaweed might be envious of a project around the corner, made in collaboration with its more primitive relative, red algae. Australian designer Jessie French has developed an organic algae-based vinyl as an alternative to synthetic window decals, contrasting the few weeks it takes for algae to grow with the many hundreds of years it takes for man-made plastics to decompose. The museum considered using it for the exhibition signage, but the carbon footprint of shipping it from Australia sadly put paid to that idea.

Elsewhere there are some ingenious examples of “nature-based infrastructure”, from 3D-printed coral reefs and sea walls, full of little ridges and holes to encourage marine life, to floating breakwaters that mitigate storm surges, which are also designed as habitats for oysters. Indigenous wisdom gets a look-in too, with baskets woven by the Ye’kuana people of the Venezuelan Amazon, who ask the permission of the forest before using its products, and a film that highlights the Inga people of the Colombian Amazon and their hallucinogenic use of ayahuasca. Just like the Ant Farm collective, it sometimes takes a little something extra before we can fully communicate with our more-than-human cousins. An altered state might help the exhibition-goers, too.

In the end, it is (perhaps appropriately) nature itself that steals the show. Each section begins with a group of historic artefacts in vitrines, including a beautiful collection of animal nests. Marvel at the grotto-like wood pulp habitat of the European wasp, or the dainty nest of a hummingbird, fashioned from antibacterial lichen and cobwebs for elasticity, or the tiny clay capsule of the solitary potter wasp, hanging from a branch. The female wasp sculpts these little pots from mud and saliva, before laying an egg inside and stocking it with provisions of paralysed caterpillars. Now there’s some more-than-human maternal cunning.

3 months ago

52

3 months ago

52