Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has said its aid workers are “heartbroken” after the medical NGO was forced to suspend all of its healthcare services in Port-au-Prince for the first time in three decades, leaving Haitians in the violence-ravaged capital without a critical lifeline.

The international non-profit said it had no choice but to halt all operations on Wednesday after staff were repeatedly attacked and received death threats from armed vigilantes and the national police.

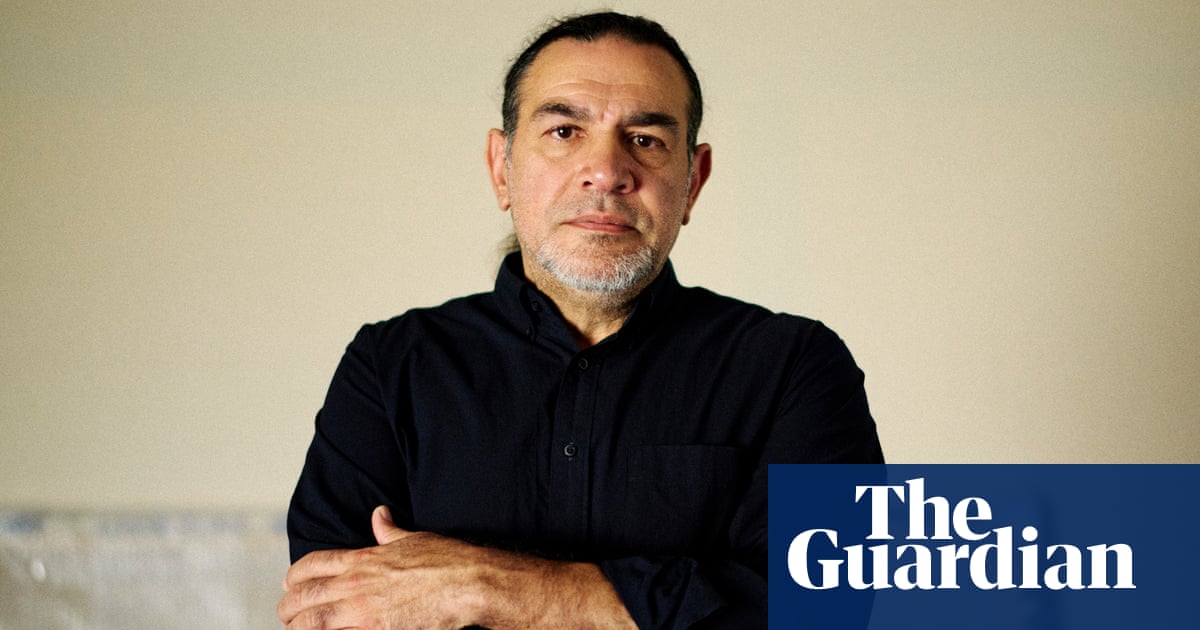

“Suspending the activities of MSF in Haiti has been a heartbreaking decision,” said Diana Manilla Arroyo, MSF’s head of mission for the country. “We have been in Haiti for more than 30 years and we know that healthcare services have never been as limited for the Haitian people as they are now.”

The indefinite suspension of MSF’s Haiti operations follows an incident earlier this month where armed police officers and vigilante groups stopped an MSF ambulance carrying three young gunshot victims.

The armed men slashed the ambulance’s tires and teargassed MSF staff inside the vehicle to force them outside before shooting two of the patients dead, the NGO said.

The organisation had hoped to continue working despite the incident but staff have faced death and rape threats another four times since, making its operations untenable, Arroyo said. “MSF works in many parts of the world with high levels of insecurity, however, we expect minimum levels of safety for our teams.”

MSF has paused services at particular facilities in Haiti on several occasions in recent years due to gang violence, including occasions where bullets have flown through hospitals. However, it has never ceased operations entirely, a move that will leave nearly 5,000 patients a month without medical care.

The decision is a blow to Haitians who are facing the worst hunger crisis in the western hemisphere while caught in the crossfire of brutal gang wars.

Hospitals have been burned down in violent insurrections this year, doctors have been murdered and essential medical supplies have dried up, leaving 2 million people in Port-au-Prince with scant options for medical attention.

Aid workers provide a vital lifeline for Haitians seeking treatment for soaring prevalence of gunshot wounds, severe malnutrition and sexual violence.

MSF’s five hospitals treat more than 1,000 patients a week on average, including 50 children with emergency conditions and more than 80 survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

Patients are frequently referred to the NGO’s hospitals by other civil society groups, as it is one of the few organisations equipped to treat the most complex and life threatening cases, said Flavia Maurello, head of the Italian charity AVSI in Haiti.

“All of us are affected by this decision and we must now try to figure out how to cope with it,” said Maurello.

Haiti has fallen into ever-deepening insecurity, chaos and political turmoil since its president Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in July 2021.

Armed gangs, which control 80% of the capital, forced out Moise’s successor, Ariel Henry, in March.

Garry Conille was tasked with stabilising the country when he was named prime minister by the country’s transitional presidential council in May, but he too was sacked last week as gangs ran riot in the capital terrorising the local population.

The country has pinned much of its hope of restoring order on an UN-backed international security mission, but only 400 Kenyan police officers have been deployed to the Caribbean nation so far and have failed to turn the tide.

At least 28 people were killed this week as the gangs came together to lay siege to neighbourhoods such as Haut Delmas and Pétion-Ville – upmarket neighbourhoods previously considered safe havens.

If the armed groups succeed in expanding their control of the capital, the city could be cut off from the rest of the country and the world, said Laurent Uwumuremyi, Mercy Corps’ country director for Haiti.

“If Port-au-Prince becomes completely cut off, the humanitarian consequences will be catastrophic. Hospitals, already overwhelmed, will run out of essential supplies,” said Uwumuremyi. “Food insecurity will escalate to famine-like conditions, and access to clean water and health services will deteriorate further. The isolation of the capital would sever Haiti’s lifeline to international aid and exacerbate the suffering of millions.”

MSF said it has asked the police, the transitional presidential council and the international security force to guarantee its safety so it can resume its operations.

3 months ago

58

3 months ago

58