On a Sunday in October 1997, Eve Henderson looked down at her husband, Roderick, as he lay in a hospital bed, unable to make sense of what she saw. She was, she says, “a block of stone”. They were in the neurological ward of a huge hospital on the outskirts of Paris. Travelling on the Métro, the hospital name scribbled on a scrap of paper, it had taken Henderson an hour to find. Roderick looked comfortable when she arrived; he was a good colour, but there was a round red mark in the centre of his forehead and a small tube inside his mouth, attached to something she later learned was breathing for him.

“He looked fairly alive,” says Henderson, “and I just stood there. A doctor came in. She was in tears and I thought: ‘Bloody hell, am I meant to be crying?’ You’ve got no emotion, you’ve got nothing. You don’t know what to say or where you are. That’s what shock does to you.”

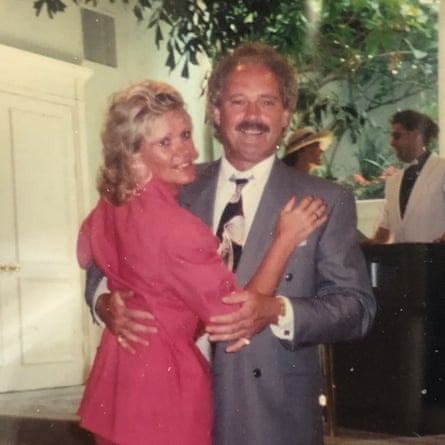

Less than 24 hours earlier, on the Saturday night, Henderson, her husband, their two adult children and their partners had been toasting Roderick’s 54th birthday on the Seine. “We’d been dressed up, suited and booted, on a bateaux-mouche.” All six had arrived in Paris for his birthday weekend the day before, travelling by Eurostar, sharing champagne and bacon rolls on the way.

“When this happened, Roderick and I had been married for 32 years. We’d seen all the ups and downs,” says Henderson. “We were broke when we started – you have the kids, things get easier.” They lived in Swanley, Kent. Henderson worked part-time for Asda as, she says, “a glorified secretary”. Roderick was a tool-maker, an engineer. “That was part of the reason behind the weekend,” she says. “Eurostar was fairly new and he wanted to see the tunnel.”

When they had disembarked the bateaux-mouche that Saturday evening, the group had separated. The three men – Roderick, their son, Scott, and their daughter’s husband, Andrew – went on for a last drink. The three women returned to the hotel. Henderson was fast asleep when Scott woke her hours later, telling her that they had been attacked. The men had been to a bar on the Champs-Élysées, then left, walking no more than 30 yards before a gang of youths on inline skates came from nowhere. “There was no interaction and it was over in minutes,” says Henderson. Scott and Andrew were kicked at the knees and went straight down. Her husband was punched in the throat – the autopsy confirmed that it broke his larynx – then kicked in the centre of his head as he fell.

To this day, there is no explanation and no one has ever been charged. (It was months before police appealed for witnesses or even brought in the murder squad.) It’s believed that this was a street gang, who had intended to rob them but were scared off by the crack of the kick to Roderick’s forehead – it’s possible they had not meant to hurt him seriously.

A crowd gathered and all three men were taken to hospital by ambulance. Scott and Andrew were quickly discharged and they returned to the hotel in shock, with no idea what the hospital was called, or where it was, or that Roderick was now fighting for his life with a bleed on the brain. While their hotel concierge phoned around trying to locate him, Henderson watched the street from the balcony, expecting her husband to appear any minute.

Now, 28 years later, Henderson will tell you that there could be few things worse than the murder of a loved one – but a murder abroad is one of them. The shock, the grief, the loss are the same, but instead of support, there’s a gaping void. “You’re a world apart,” she says, “a stranger in a strange city, floundering in the dark. You’re speaking a different language, dealing with a different legal system, different policing, different everything. You just feel so hopeless and alone. That’s the overwhelming feeling.”

Although the days that followed are now, thankfully, a faded blur, there are some moments Henderson will never forget. The family were meant to be going home that same Sunday, so their hotel rooms were no longer available. “We had no cash left and we didn’t have credit cards then – lots of people didn’t.” She remembers queueing at the British consulate, along with everyone else waiting for visas, finally speaking through the glass to the receptionist, explaining that her husband was on life support, asking for practical help and getting none. She remembers eventually finding another hotel, sharing a bed that night with her daughter, wide awake, completely unable to reach over and cuddle her.

After a few days, doctors explained that they would be removing Roderick’s life support. “I’ve watched these scenes in documentaries, and the families are involved in the decisions, there’s a nurse supporting them, someone putting their arms around you,” she says. “It was nothing like that. No one came near us. We were given no say or control over when it would happen – we were just told to say goodbye.”

In the midst of all this, on the instruction of the British consulate, Henderson had to find her way to a police station and request an “incident number”. The first police officer insisted that it was a civil matter, that her husband was “a heavy man”, that he “fell and hit his head”. She was told she needed to find a lawyer and an undertaker. “I sat there in the police station, in tears,” she says. “You don’t even know your own phone number, and now you need to repatriate a body?”

Her boss at Asda stepped in, engaged a French law firm and paid for Roderick’s repatriation. His unwashed clothes from that night arrived home in a hospital bag, cargo-class. Someone from the British consulate collected Roderick’s jewellery – a watch, an engagement ring and a wedding ring – but the Foreign Office refused to return them until Henderson had been granted probate.

“All of this, this lack of empathy, did me damage,” she says. “The trauma of not being helped left a mark. I remember back home, looking at my grandchildren, thinking: ‘I can’t even pick you up.’ I had nothing to give. I was going to bed, thinking: ‘I want to wake up in five years’ time when this will all be in the past.’”

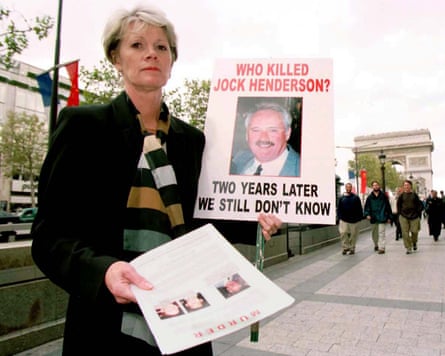

Fighting for a proper investigation was the first step forward. She made appeals in French papers; she returned to Paris with a TV news crew and stood on the spot where the attack took place, handing out leaflets appealing for information. Henderson remembers writing to the father of Caroline Dickinson, the British schoolgirl murdered in a French youth hostel in 1996. (Her killer remained at large until 2001, with her family fighting tirelessly for a proper investigation.) “He called me and said: ‘If you start this, you need to know you’re on your own – there’s no support out there,’” says Henderson. “He put me in touch with Roger Parrish, whose daughter Joanna was murdered in 1990 by a French serial killer. So many horrors. Roger educated me about the inquest system and the justice system. It was such a steep learning curve.” (In fact, it took more than 30 years for the Parrish family to win any kind of justice.)

When Henderson contacted the UK charity Support After Murder and Manslaughter (Samm), she was told that they didn’t take cases from abroad, but they introduced her to another family that had approached them. Shirine Harburn, 30, had been travelling in south-western China when she was found stabbed and murdered on a mountain. “Her sisters and her boyfriend were fighting for justice. They were young and articulate,” says Henderson. “They got their MP involved. The Chinese sent her body back still clothed and our police analysed it for DNA, then actually went out there. They got the two men who did it. Seeing all this, meeting these families, was so important for me. I was able to sit back and learn so much.”

The more she learned, the more she wanted to change. In 2001, Henderson helped set up Samm Abroad, which later became Murdered Abroad (MA), a charity and peer support and action group. “It gave me a purpose, a cause,” she says.

It also made her an unpaid expert on the complexities of homicides abroad. Approximately 4,000 British nationals die overseas each year. This includes about 80 official homicides – more than one a week – but there will also be many more “suspicious” deaths. “These are deaths where families might be told, ‘He drove into a telegraph pole,’ or ‘She fell off a balcony,’ or ‘It was suicide,’” says Henderson. “The Foreign Office don’t challenge any of it. We work on the basis that if families believe it’s a homicide, we’ll welcome them.” Most cases take much longer to resolve than cases here. Five years isn’t unusual; many stretch on for decades.

The guidance MA gives to families could cover anything. “It could be repatriation, or how to engage a lawyer in a foreign country, or what to do about the inquest,” says Henderson. “Every country has a different judicial process and we know a bit about many of them.” The financial cost can also be ruinous for families – paying lawyers, attending trials, paying for translations of documents, the time off work. “We’re not covered by the Victims’ Code,” says Henderson. “There’s no criminal injuries compensation unless there’s a scheme in the country where it happened, and even then you’d need to pay a lawyer to claim it.” One 2011 survey of MA families found that their ordeals had cost them an average of £59,000. “One father whose son was murdered in Greece got the sack because of all the time he was spending on the case,” says Henderson. “We helped him write a letter to his mortgage provider and they gave him a mortgage holiday.”

All this has helped channel her own grief. “It keeps me going,” she says. “I can go out there and help all these other people in practical ways, but sometimes you do ask yourself: what can I do for my own kids? It’s almost like you can’t help your own. They lost their dad. I can’t bring him back.”

Counselling has also helped her. “When I started, I cried solidly every time I went,” she says. “My counsellor was brilliant, a life-saver. It became somewhere I could offload and she helped me set small positive goals. I carried on going from time to time for 20-odd years.”

Henderson tries not to picture the life she and Roderick might still be living. “You don’t go there – you have to try not to be bitter,” she says. “Your world changes, it collapses, but you don’t want to roll over.” After the murder, Henderson rented out the family house and moved in with her sister and 90-year-old mother, who have both since died. She now lives alone in Bexley, south-east London.

“Even now, you get odd moments. There’s something about sleep that takes away your memories, so you might wake up, reach out to the other side of the bed and he’s not there,” she says. “He loved our grandsons – he was a lovely grandfather. He’d take them to the shed where his tools were and do all the ‘boy things’. For years afterwards, I’d think about what he was missing – then, at some point, I had to have a rethink. He doesn’t know about any of this; it’s me that’s having to live without him. We have the life sentence.

“We have guest speakers at our MA events and one was a clinical psychologist and trauma specialist, David Trickey. He said that when something like this happens, it’s like you have a big black hole blasted into your life. That hole never goes away – it doesn’t get any smaller – but over time, years pass, and your life around it gets bigger. I understood that. One grandson married on a beach in January. I’ve got two great-grandchildren now: Baby Violet, who came along two weeks ago, and Daisie.

“You have to pick out the good bits or you’d go under,” she says. “I’m still here, I’ve got my marbles and I’m still passionate about MA. I can’t bear to think that other people are still suffering the same way I did. So I’ll fight on.”

2 weeks ago

26

2 weeks ago

26