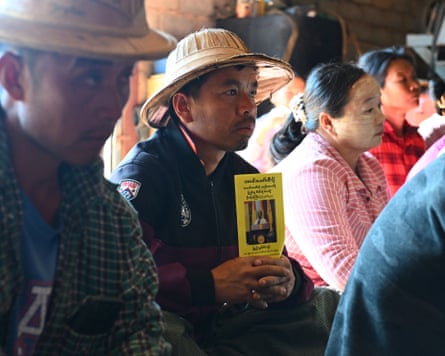

Five years after Myanmar’s junta ousted the country’s last elected government, triggering a civil war, voting is set to begin this week in national elections.

The junta claims the vote is a return to democracy, but in reality the one-sided and heavily restricted poll has been widely condemned as a sham designed to keep the generals in power through proxies.

The first of three rounds of voting is due to begin at 6am on 28 December. More than 100 townships, including the commercial capital of Yangon, will vote in this first phase of the elections, followed by another 100 in the second phase on 11 January. The details of a possible third phase are yet to be announced.

Who is running?

There will be 57 parties on the ballot on Sunday, but the majority are perceived as being linked to or dependent on the military. Only six parties are running nationwide, with the rest only running in a single state or region. The military-backed Union Solidarity and Development party has fielded the largest number of candidates and is in effectrunning uncontested in dozens of constituencies.

The party of Aung San Suu Kyi, which won a landslide victory in the 2020 election but was ousted in the 2021 coup, will not be running. Her National League for Democracy was dissolved after it refused to comply with a demand to register with the junta-backed Union Election Commission. Dozens of ethnic parties were also dissolved.

According to election monitoring group Anfrel, 57% of the parties that ran in the 2020 general election no longer exist, even though they received more than 70% of votes and 90% of seats.

So is the election free and fair?

Several countries, the United Nations, and rights groups have described the elections as a sham designed to keep Myanmar’s ruling generals in power through proxies, although the junta insists the polls have public support.

The elections will be held amid a raging civil war, triggered by the coup which ousted Aung San Suu Kyi’s government and ushered in the military junta. Voting will not take place in rebel-held areas, which cover large swaths of the country.

Meanwhile, the junta has arrested more than 200 people for violating draconian legislation forbidding “disruption” of the poll, including protest or criticism on social media. Those convicted of breaking the law can face punishments ranging from three years in prison to the death penalty.

The law has been used against young people putting up boycott stickers, film directors and artists who posted reactions on social media, and to charge journalists, according to rights groups.

The military government has dismissed international criticism, with a spokesperson for the military government saying Myanmar will “continue to pursue our original objective of returning to a multiparty democratic system”.

Which countries are supporting the vote and why?

Myanmar’s biggest ally and northern neighbour China has thrown its support behind the junta, and its decision to hold elections. Analysts say that China views the vote as the country’s best path back to stability.

Many western governments consider the vote a sham. UN human rights chief, Volker Türk, said this week that the elections were taking place in an atmosphere of “violence and repression” and that military authorities “must stop using brutal violence to compel people to vote, and stop arresting people for expressing any dissenting views”.

The US secretary of state, Marco Rubio, said in October the US was still formulating its policy on Myanmar. The US has previously been a strong critic of the junta, though earlier this year it lifted sanctions designations on several military allies. In November the US Department of Homeland Security said there had been improvements in governance in Myanmar, and cited the election as justification for removing temporary protected status for Myanmar nationals – an assessment rights groups have strongly disputed.

Lashing back at foreign criticism of the poll last week, the junta spokesperson Zaw Min Tun told reporters: “It is not being held for the international community.”

What about Aung San Suu Kyi?

Myanmar’s former de facto leader has been siloed in military detention since the 2021 coup, but her absence looms large over the elections.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s reputation abroad is heavily tarnished over her government’s handling of the Rohingya crisis. But for her many followers in Myanmar her name is still a byword for democracy, her absence on the ballot an indictment it will be neither free nor fair.

She is serving a 27-year sentence for offences ranging from corruption to breaching Covid-19 restrictions, charges which rights groups dismiss as politically motivated. Little has been seen or heard of her since her arrest and concerns over her health in custody have been raised by her family and supporters.

“I don’t think she would consider these elections to be meaningful in any way,” her son Kim Aris said from his home in Britain.

2 months ago

59

2 months ago

59