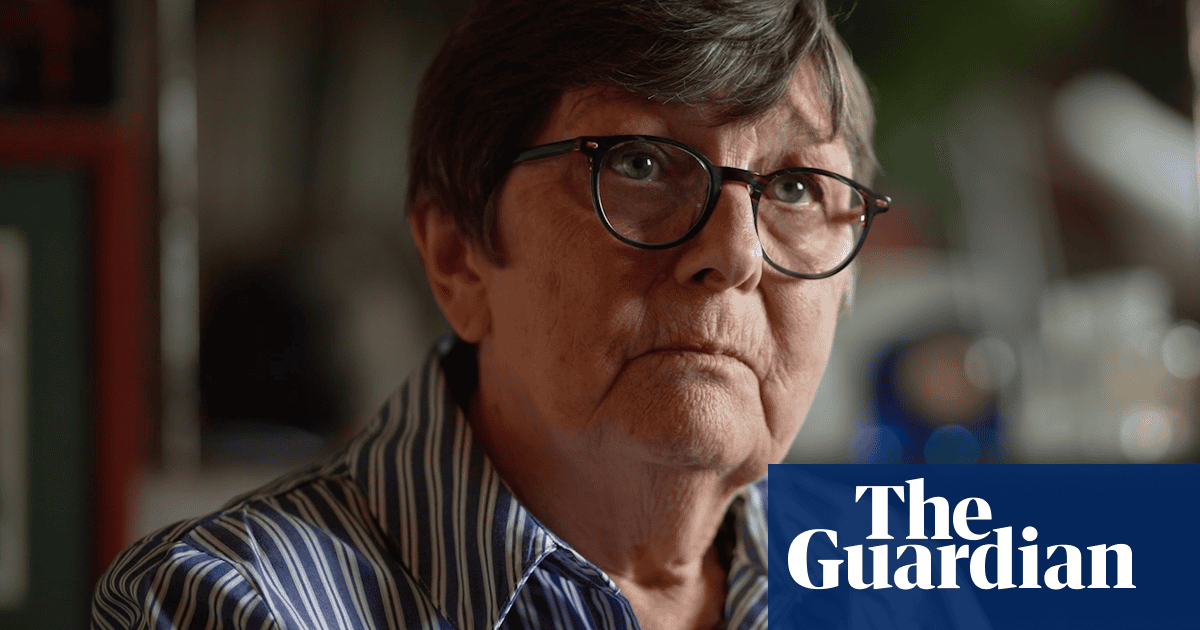

‘We’ve already got one,” sneers a snotty French knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. With that holy grail of British history, the Bayeux tapestry, about to be lent by France to the British Museum, we could say the same. In 1885, Elizabeth Wardle of Leek, Staffordshire, led a team of 35 women in an extraordinary campaign to embroider a meticulous, full-scale replica of the entire early medieval artwork. With Victorian energy and industry they managed it in just a year and by 1886 it was being shown around Britain and abroad.

Today that Victorian Bayeux tapestry is preserved in Reading Museum, and like the original, can be viewed online. Are there differences? Of course. The Bayeux tapestry is a time capsule of the 11th century and when you look at its stitching you get a raw sense of that remote past. The Leek Embroidery Society version is no mean feat but it is an artefact of its own, Victorian age. The colours are simplified and intensified, using worsted thread, as Wardle explains in its end credits, “dyed in permanent colours” by her husband Thomas Wardle, a leading Midlands silk dyeing industrialist.

The Wardles were friends with the radical craft evangelist William Morris – a clue that Elizabeth’s epic work of replication should be seen as part of the Victorian passion for medieval history that encompassed everything from neo-gothic architecture to Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe and Morris’s Kelmscott Chaucer – in which the poems are illustrated with woodcuts. In this Victorian dream of the past, sympathies were very much on the Saxon side. The Norman conquest was seen as a national tragedy in which traditional Anglo-Saxon freedoms were crushed by the “Norman Yoke”. It’s ironic that this underdog version of British history, with brave Saxons defying the wicked conquering Normans, prevailed at a time when they were themselves conquering or colonialising much of the planet. That immigrant Victorian Karl Marx wrote that when people are “revolutionising themselves and things … they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes”. This perfectly describes 19th-century Britain, which hid its creation of modern industrial capitalism in medieval styles. And when it came to reproducing the Bayeux tapestry, it was a new technology that made it possible – photography.

Wardle and her team based their embroideries on what was considered at the time a nationally essential photographic project. In the 1870s, the British government itself commissioned Joseph Cundall to photograph the entire Bayeux tapestry. You can picture his intrepid expedition setting out by the boat train with red-coated soldiers to guard the camera and a team of bearers. A Ripping Yarn.

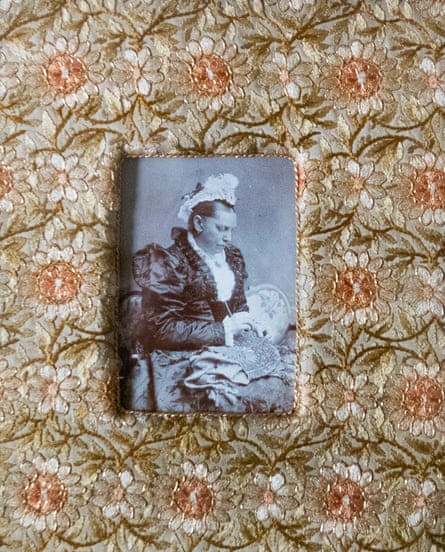

Cundall’s monochrome photographs were hand-coloured by art students back in Britain – and censored. Like other medieval art, including manuscripts illuminated by monks, the Bayeux tapestry has a plenitude of monsters and obscenities in its marginalia, including male nudes with graphically depicted penises. One naked man stands with a flamboyant erection, which may be part of the tapestry’s realism about the psychology of war. When the Leek Embroidery Society borrowed a set of Cundall’s photographs, they of course copied the false colours and underpants from these supposedly objective recordings.

after newsletter promotion

In fact, this is not the only full-size Victorian replica of the tapestry. Cundall created his own continuous photographic replica, mounted on two ornate wooden rollers so that you can scroll through it in your private library. Perhaps this is what its most recent private owner, the late Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts, used to do. When his estate went on sale his “tapestry” got much less attention from the media than other treasures such as his first edition of The Great Gatsby. But it was sold for £16,000 – to the Bayeux Museum in Normandy. At least in Bayeux it’s in safe hands, just as the original has been for at least 600 years.

3 months ago

43

3 months ago

43